Although the strikes of 1934 happened in Minneapolis, they affected many people in our area who worked in the City. Much of the following information is from “The Dunne Boys of Minneapolis” by Dale Kramer, as published in Harpers Magazine, March 1942. This is a stripped-down account to be sure.

The Dunne Brothers organized a truck drivers’ strike in Minneapolis that shut down commerce for five months and featured violent confrontations. Brothers Vincent, Miles (“Mickey”), Grant, and Fenton Dunne were Trotskyites during the time that Trotsky had split from Stalin after the death of Lenin.

The Communist Party was becoming more popular after WWI, and although it went underground for awhile in the wake of action by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer (the “Palmer Raids”), Minneapolis was ripe for labor agitation in the early days of the Depression. The Gateway had been the place for laborers to be hired for railroad gangs, lumber camps, or harvest crews. When those jobs evaporated, some got jobs in other industries, but the area deteriorated into a skid row that would persist until urban renewal in the 1960s. Social unrest was inevitable and there were many political factions competing for support. Much of the story of the strike has to do with battles between rival union organizations as it does the drivers and their employers.

Vincent Dunne had obtained a job “teaming,” which involved handling horses. He worked himself into the class of express drivers, “sweeping through the streets ahead of the rest.” As the brains of the bunch, his efforts were concentrated on unionizing the teamsters in order to obtain higher wages, more reasonable hours and better working conditions.

Vincent Dunne

The leaders of Local 574, left to right: Grant Dunne, Bill Brown, Miles Dunne, and Vincent Dunne upon their release from the military stockade in 1934. Far right is Communist League of America lawyer Albert Goldman.

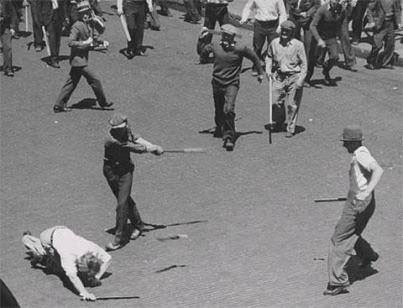

The first strike of 1934 started on May 16 and was centered on the market district north of Hennepin Ave. (Second Ave. North between 5th and 6th Streets) On May 19 the strike became violent, as strikers battled police and hundreds of ersatz deputies: “observers gave the edge to the drivers, but the battle was not decisive.”

The battle caused such a commotion that 25,000 people showed up the next day, May 20, to watch the violence, and radio coverage ensured that everyone could keep score. On one side were 700 police and about 1,000 deputies – one in a football helmet and one in his polo outfit. Deputized business owner Arthur Lyman was found dead, and special policeman Peter Erath died later on. Union members referred to the skirmish as the “Battle of Deputies Run.” Governor Olson, a Farmer-Laborite, reluctantly sent State troops to keep order. Fighting was over by May 22 with the workers seemingly the victors.

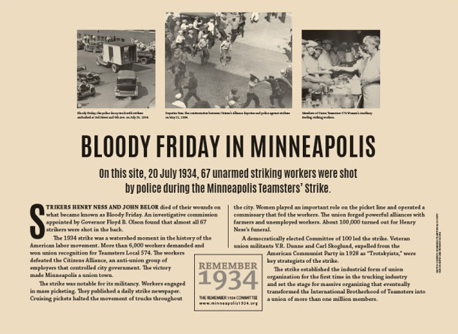

The second strike began on July 16 in the Warehouse District, where strikers blocked truck delivery. On July 20 (“Bloody Friday”), hundreds of workers gathered at the intersection of 6th Ave. and 3rd Street No. in downtown Minneapolis, about where Target Field is today. Chief of Police Mike Johannes (“Bloody Mike”) decided that his men would being moving goods again. Police brought two trucks to the Slocum Bergren Company, loaded goods, and left. (Slocum Bergren was located at 5901 Wayzata Blvd. in St. Louis Park by 1956 – the present site of Spring Hill Suites.)

In the afternoon, a third truck left a wholesaler with a heavily armed police escort. The unarmed strikers attempted to stop it, and Johannes ordered police to open fire on them. Two men were killed: Local 574 striker Henry Ness and unemployed worker John Belor. 67 were injured, most of them shot in the back. Governor Olson declared martial law.

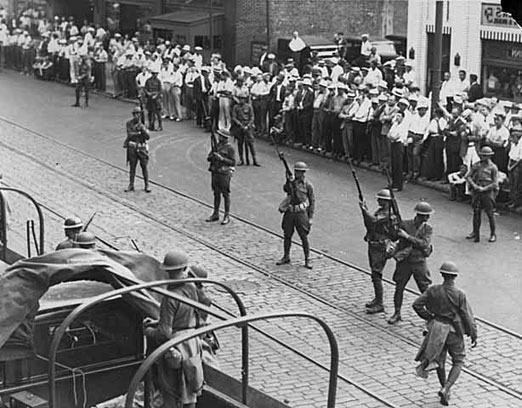

On July 26 Governor Olson declared martial law and 4,000 National Guardsmen, headquartered at the State Fairgrounds, patrolled the city.

On August 1, 1934, the National Guard raided strike headquarters and arrested Vincent Dunne and others, but backed down and reversed the actions soon afterwards.

Mediation leaders Father Francis J. Haas and Eugene H. Dunnigan shared handshakes with Governor Floyd B. Olson after the strike was settled on August 18. It had lasted 36 days.

The Dunne Brothers were charged with sedition in 1940. Before the trial, brother Fenton had dropped out, and Grant shot and killed himself. Vincent and 17 others were convicted of conspiring to undermine the loyalty of U.S. military forces and publishing material advocating the overthrow of the Government. They were found not guilty of sedition. Miles and four others were acquitted of all counts. Vincent was sentenced to 18 months in jail. Despite their heavy-handed ways, Minnesota labor leaders credit the Dunnes with making Minneapolis a union town.

There is much more to the story. An extremely detailed four-part article written by Ron Jorgenson in 2009 is posted at the World Socialist Web Site.

Postscript: A plaque marking the location where police shot and killed Henry Ness was unveiled on July 18, 2015, on the side of the Sherwin Williams building on Third Street North.

Above two images from Eric Roper’s article in the StarTribune, June 22, 2015