Most St. Louis Parkites who were in residence in 1977 remember the devastating fire at the Belco grain elevators on May 11 of that year.

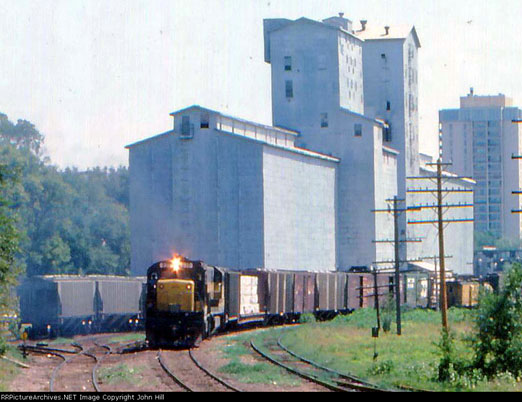

The Great Western Grain Elevator was built in about 1893; an article on April 1 of that year in the Minneapolis Tribune stated that the arrangements had been completed. It was located on the Minneapolis and St. Louis railroad tracks at 3120 Glenhurst Ave. in the Manhattan Park neighborhood.

In 1904 it suffered damage in an August tornado.

The Minneapolis Tribune of March 23, 1910, reported: “Sparks from a passing locomotive set fire to a pile of lumber near the Great Western elevator, near St. Louis Park, last night, and for some time the big warehouse was threatened. Water was scarce and much of the lumber was consumed before the fire fighters could get down to business. Before a switch engine could be secured, one box car was destroyed, but a string of cars was pulled out in time to save it from the flames. The loss is about $3,000.”

On June 20, 1911, the Minneapolis Tribune reported that the Great Western Grain Company was incorporated and would take over the properties of the Great Western Elevator Company, which constituted 73 grain elevators in North and South Dakota. “The Great Western terminal elevator is located at Manhattan Park and has a capacity of 1,500,000 bushels.”

In 1913 it was owned by Hales Hunter and held barley.

Burton F. Hales (1853 – 1930). “In 1910 he organized the Minneapolis Malt & Grain Company and in 1912 the Interstate Malt & Grain Company of Minneapolis, Minnesota, having plants also at Waterloo and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and the same year purchased the Kasota Elevator Company at Minneapolis, Minnesota. In 1916 he helped to organize the Hales & Edwards Company, the name of which was later changed to Hales & Hunter Company, with a plant at Riverdale, Illinois, for putting up feeds, and became one of the largest manufacturers of animal food.”

In 1918 it was owned by Union Elevator Co., which also owned at least one house in the neighborhood.

In 1922 six damage suits totaling $18,000 were filed by residents of Manhattan Park against Hales & Hunter. The article in the July 19 issue of the Minneapolis Tribune stated that “The complaints allege that dust, weed seeds and chaff from the elevator sift into their homes and cisterns and have caused their gardens to be overrun with weeds.”

In 1926 it was owned by Hales Hunter (The foreman was Van McKusick, who lived at 3040 Inglewood). Hales Hunter had water connected in 1938.

By 1939 it was called the Belco Elevator, still owned by Hales Hunter.

The elevators had been owned by the Burdick Grain Co. of Minneapolis since 1950. Allan L. Burdick was the Chairman of the Board, and Vernon Geiger was the President of the Company.

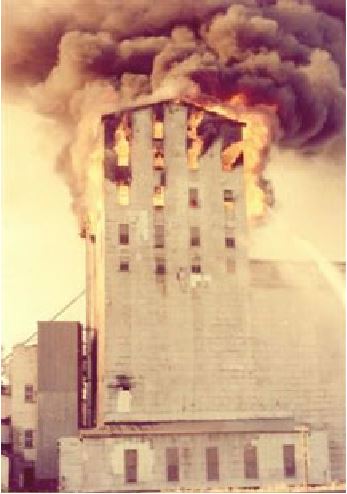

THE BELCO ELEVATOR FIRE

The elevators burned down in a spectacular inferno on May 11, 1977. At about 5:30 p.m., 28-year-old David Berscheit was cleaning corn in #1 when a small fire started. He tried to put it out with a blanket, but the 500,000 bushels of corn in the wooden structure exploded, throwing Berscheit and leaving him with burns over 60 percent of his body. The fire spread to the #2 elevator, which held 1 million bushels of barley. Chief Luke Stemmer recalled “The fire was believed to have started as a result of a series of explosions, each one bigger than the one that proceeded it, with the last on blowing the roof off of Belco 1’s head house.” Flames shot 100 feet in the air, and the smoke was visible 30 miles away. Thousands of spectators converged on the site.

Doug Adams, a student at Park High at the time, remembers:

I did not hear the assembly that told us of the dangers of going down there or what would happen if you did, and I almost got suspended for going there and taking photos, but I was in camera club. I took two photos and put them together.

The fire raged for five hours, exacerbated by winds of 12-15 mph. Some fire fighters worked up to to 26 hours in a row. Backup crews came from over a dozen neighboring jurisdictions, including Minneapolis, St. Paul, Minnetonka, Hopkins, Golden Valley, Richfield, Eden Prairie, West Champlin, Bloomington, Edina, Brooklyn Park, Brooklyn Center, Shakopee, and Chaska. Part of the property was in the Park and the other in Minneapolis. Although there are reports that the equipment of Minneapolis and St. Louis Park were not compatible, Stemmer said,

Our equipment was compatible so that was not an issue. The big issue was a lack of water into the area and the fact that there was no mutual aid agreement between Minneapolis and St. Louis Park. Minneapolis would ultimately go to 5-5 or fifth alarm at this fire in an effort to keep it in St. Louis Park and not spread into Minneapolis which was just feet away. Through out the night every engine and ladder company in Minneapolis saw action at this fire.

The 4000 block of 31st Street was evacuated, displacing 200 residents as a precaution against flying ash that landed on rooftops. Neighbors had expressed concern about the structures, citing several small fires in the past.

The insurance company hired the Gregerson Salvage Company, which managed to save 70-90 percent of the grain for use as feed. The Burdick Grain Co. paid the City $1,412 for damage to their equipment. In July 1977, remaining grain, hit by water, had begun to ferment, raising complaints in the neighborhood. One resident said that “the stench of wet, burnt Cheerios lasted until 1979 or so.”

In 1999 the site was replace by the three-block long Inglewood Trails apartment complex.