Popular history is more than who were the mayors and when the highways were built. To really understand how people lived in St. Louis Park years ago, we must sometimes delve into unusual topics. This is one of them. It is by no means complete, and additional information and stories are most certainly welcome – please contact us.

Also see Environmental Activities.

Back in the 1890s, when there was so much building and activity in the Village, there was no garbage collection: coffee grounds and eggshells were put into the garden, table scraps were fed to the chickens, and butcher paper was burned in the coal-fired furnace or in the kitchen stove. Each spring the Village would have a “Cleanup Day,” when a team of horses pulling a wagon would go up each alley and Village employees would scoop up the ashes from the kitchen stove and the furnace onto the wagon. The Village would print up “dodgers” to distribute, alerting the residents of the coming of Cleanup Day. Sometimes it was free, and sometimes, as in 1914, residents paid 25 cents per load.

Minutes from the April 5, 1907, Village Council meeting refer to the Bass Lake public dumping ground.

An ad in a 1914 paper for Depew’s Transfer listed locations in Minneapolis, St. Louis Park, and Hopkins.

In April 1915, the Village Council passed an “ordinance to regulate the throwing or depositing of garbage, swill, etc. on streets, alleys or in lakes, streams, etc. in the Village…” The ordinance ran through a long list of noisome things one could not throw in the streets, including butcher’s waste, manure, contents of cess-pools or privy vaults, “or any other nauseous or unwholesome substance, fluid, or thing.” The fine ranged from $2 to $100, the jail sentence up to 30 days or until the fine is paid. That’s no longer legal, by the way.

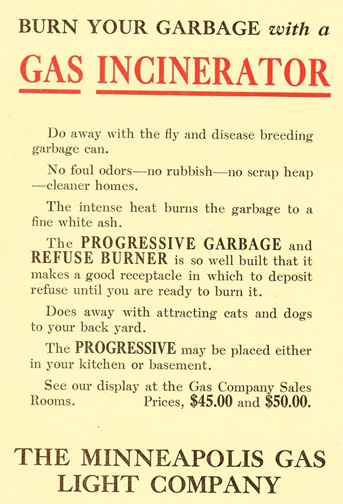

A local publication called the Bellman, put out by Donaldson’s Department Store, published this ad on February 10, 1917. Paul Arneson, who posted it on Facebook, noted that according to the timeline above, incinerators were actually being phased out by 1909.

Public dumping in St. Louis Park was a problem. In July 1920, the Village Council ordained that no dumping would be allowed in the alley between Goodrich and Summit (now Oxford). Then in April 1921, the Minnetonka Blvd. Improvement Association complained about a dump long the Milwaukee, Chicago, and St. Paul Railroad. This may have been the dump behind the Roller Garden at Lake and Minnetonka.

In 1929 Village Council Minutes noted that a system of garbage collection was needed.

In the years 1934-38, the Village still had no municipal garbage collection, but one could make private arrangements by calling private haulers, such as Aaron Anderson. Anderson, located at 2720 Vernon (Between Minnetonka Blvd. and Reformation Church), advertised as such: “Keep Your Yard Clean! Let me do it. Special Monthly Rates. Ashes and rubbish removed. Black Dirt – Sand – Gravel – General Hauling”

Another private hauler was W.C. Beihoffer. In 1935-37 he was at 3039 Natchez Ave., and in 1938 he was at 2605 Vernon (about where Benilde is now). Mr. Beihoffer charged 50 cents per month for garbage, tin cans, and glass, 75 cents to add rubbish (not to be confused with garbage…), and $1.00 to add tree trimmings and lawn cuttings. Clean ashes could be dumped on a site provided by a private owner at Lake and Minnetonka.

In a program dated October 1938 there is an ad for Suburban Sanitary & Drayage Co., at 6021 West 36th Street. This was the same address as the Village pump house. The business had two distinct services:

- Light and Heavy Hauling; Household Goods Moved and Stored

- Licensed Scavenger; Cesspools, Septic Tanks and Vaults Cleaned “The Sanitary Way”

The business was owned by Francis B. “Fritz” Bradley.

In 1939 a public dump “for ashes and clean rubbish only” was located at 5600 W. Lake Street behind the Holmberg and Hermstad Gas Station. Another one was located between 36th and 37th, Princeton and Ottawa.

In 1941 Fritz Bradley got the idea to fill the 25 ft. hole at 36th and Princeton that was left by gravel excavation with garbage, reclaiming it as “useful tax-producing land.” Bradley was contracted by the Village to make weekly collections of garbage. An article in the Dispatch was titled “No Flies, No Rats, with Unique Garbage System.” In 1943 householders were required to place their garbage in fly-tight cans. The company kept the City’s garbage contract through the 1950s. An article in the 1944 Dispatch noted the free dump north of 36th and Princeton.

In June 1945 William Nelson, 4080 Toledo, petitioned the Village Council to post a no-dumping sign on the east side of Toledo near 40th Street.

On February 14, 1947, the Dispatch announced the creation of the Excelsior Blvd. Dump, located at the site of Rice Sand and Gravel on Excelsior Blvd. This would later be known as the Beltline Pay Dump.

In September 1947 and again in 1949, Charles Goldblatt was cited for a dump between Highway 7 and Lake Street, west of Hampshire.

The lot that is now 3340 Webster was a dump in 1947, complete with fires and rats. The lot was built on in 1961.

In June 1948 we read of a “scavenger manhole” at 36th and Wooddale.

In 1948 Charles Goldblatt was charged with public dumping on three lots. One was located on either side of Highway 7, east of Louisiana. Another was in the Highway 7/Oregon/Lake area.

In 1948 Chester A. Jensen of Edina requested a permit to operate Sam Elchuck’s dump at the old Rice Sand and Gravel pit.

In April 1949, citizens protested the condition of the dump located in “lowlands” west of the Belt Line, south of the Great Northern railroad. The land was owned by Arthur J. Eaton (of the Pastime Riding Arena) and the operating permit was held by Morton Leder of Minneapolis. The permit was pulled the next week, at least temporarily.

In June 1949, contractor Sam Holt was cited for piling up rubbish, kindling, and logs on land that would become the Park Trails Apartments on 36-1/2 Street. Curiously, the complaint was made by another builder, Robert Johnson, who lived at 3811 Princeton.

In August 1950, Dr. Darby ordered the Bowman Dump on W. 35th Street to be covered and filled. Harold Olson was contracted to carry it out.

In the fall of 1951, Zephyr Oil, which operated a gas station at 5050 Excelsior (later the site of Citizens Bank) applied for a public dump permit north of the station, fee $100. In 1954, the gas station requested permission to build a fence to screen the view of the dump.

A July 1951 headline screamed “Garbage Dump Must Go Say Aroused Aquila Ave. Folk.” They were complaining about the Village Garbage Dump, which had been a gravel pit between Aquila and Boone, south of Minnetonka Blvd. This is where Suburban Sanitary Drayage dumped household refuse.

In a December 1951, G.M. Orr Engineering recommended that the Village not purchase an incinerator, but instead open another dump. They pointed to 75 acres bounded by St. Louis Ave., Princeton, and 26th Street. Nevertheless, the incinerator prevailed. In 1952 Orr was hired to construct the incinerator.

The contract for Suburban Sanitary Drayage was renewed for 1952 and ’53, but at first only until the new incinerator was completed. Services were rendered for 93 cents per resident per month. The Minneapolis suburbs generally shipped their garbage to neighboring hog farms.

In October 1952, citizens were asked not to burn their trash (including leaves) in the streets.

Dumps everywhere in 1952-55:

- The Veterans Tree Service, Washington Ave, was cited for dumping rubbish at 28th and Hannah Lake.

- Elliot Anderson had a dump north of 16th Street, west of Colorado, and was cited for having an open cesspool behind his house that was leaching into the water. He and his wife owned the 30 acre Elliot-Erskine Sand and Gravel Co. Also cited was property at Hampshire and Wayzata Blvd.

- Dr. Darby (the public health officer) approved a dump at Minnetonka Blvd. and Virginia.

- The area that is now the Belt Line Industrial Park (south of the tracks, east of Highway 100, north of 36th Street) was designated as a dump site in 1952.

- David A. Klatke, Sig Johnson owned a dump north of Cedar Lake Road at the Great Northern bridge. It contained refuse, tin cans, plaster, and industrial waste, and was covered with sand.

- There was another dump at 31st and Utah (Virginia Ave. between 31st and 32nd), leased from LNC Sand and Gravel.

- Walter Pavey of 36th Street complained about the Minnesota Tree Service, which dumped old roots and trees in the area behind his house.

- A 250-signature petition requested that the Village put up 250 signs behind Minikahda Court saying “No Dumping” in the Bass Lake area. There were also 750 signatures urging the Village to build an incinerator.

- Activity in 1955 included a dump operated by Adolph Fine, north of the Great Northern tracks, west of Virginia Ave.

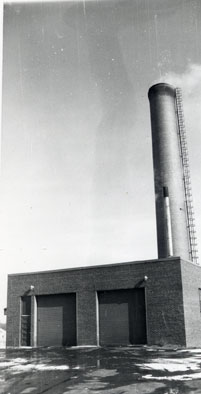

In 1953 specification for the new incinerator were spelled out: two furnaces at 75 tons each, both to have an initial firing chamber, a secondary combustion chamber and an expansion chamber. The furnaces were to have forced draft capable of firing heavy loads. The ash pits had to be arranged so that ashes may be removed without shutting the furnaces down. An accompanying building had to be large enough to allow a dump truck inside with the doors closed.

In 1953 Health official Dr. Darby testified to the Village Council that he commended the use of DDT and liberal ground covering to keep animals at bay until the incinerator was finished. Citizens were back the next meeting, though, complaining about the odor and the mess.

In June 1953, we read of a sewer manhole at Edgewood and 39th, east of the tracks, where Roto Rooter dumped cesspool sewage.

The Annual Christmas Tree Burning was held and Minikahda Vista Park on January 5, 1954. After burning the Village’s trees, members from the Figure Skating Club and other Park skaters put on a show and competition.

In February 1954, Helen Bradley and Roy Phillips of Suburban Sanitary Drayage were instructed by the Village to bury the garbage it collected until the incinerator was up and running.

In June 1954, the Village began to operate an incinerator, located west of Highway 100 and south of the Milwaukee Road tracks. Designed by architect Loren B. Abbett and built for $238,000 by G.M. Orr Engineering, its two burners could dispose of 75 tons/day. It was paid for with a $200,000 bond issue and a $5.80 yearly assessment per household. Suburban Sanitary Drayage hired the men to run it. The ashes were sent to Ernie Jacobson’s dump for top fill, but Jacobson complained that they smelled bad, so the Village had to pay him $75/month to bury them at his dump. Another problem was that soon after the commencement of operations there was a problem of sparks coming from it.

Throughout its operation, it emanated a white ash.

Almost immediately, other jurisdictions requested permission to burn their garbage in the Park’s incinerator. The Village took a wait and see attitude with requests from Bloomington, Edina, Robbinsdale, and Crystal.

In 1954 Suburban Sanitary Drayage (3612 Alabama) was owned by Roy E. Phillips and Helen L. Bradley. The company continued to have the city’s garbage contract through 1958.

In 1955 there were complaints of “promiscuous placing of garbage cans and burning of rubbish on City boulevards.” 50 years later such behavior was strictly regulated.

The 700 some businesses generally still handled their own garbage, and about a third of them had their own incinerators. In 1956 there was a dustup when the City started to restrict private incinerators. Mr. Riley of Red Owl requested a permit to install a “new type of incinerator.” It was approved on July 2.

In July 1956 Mrs. Louise M. Kelly asked permission to use her property at 22nd and Nevada as a public dump. Permission denied.

In 1956 Mrs. C.M. Pratt, President of the Brookside Garden Club, complained of “promiscuous dumping at Minnehaha Creek at the foot of Colorado Ave.”

In 1957 the incinerator could process 50 tons in 8 hours and Park needed only 40, so the City Council approved the City of Crystal’s request to burn its 7-8 tons in Park’s incinerator.

In April 1957 complaints were made that newsboys were leaving wires and wrappings in the street.

The Northside trunk and lateral sanitary sewers were completed in 1958, with the construction of sanitary sewers to serve the Southwest part of the City scheduled for next year.

Come the 1960s, the Park was the first city in the State to establish total residential trash pickup (rubbish and garbage) on a weekly basis. The contractor in 1960 was Roy Phillips and Helen Bradley dba Suburban Drayage.

In 1960 Charles. M. Friedheim ran a landfill between Zarthan and Vernon, Cedar Lake Road and the Great Northern tracks. This land undoubtedly had been excavated, and the solution to both the garbage problem and that of a huge hole in the ground was a landfill.

In 1961 councilman C.L. Hurd registered a complaint that newsboys were leaving trash at their pickup point at 5000 Minnetonka Blvd. (across from City Hall).

In 1962 the Minnegasco Appliance Stores were advertising the new Calcinator gas garbage disposer. “Make this the year to get rid of that eyesore in your back yard – the messy garbage can.” The completely automatic machine was said to be smokeless and odorless, and consumed all burnable trash and garbage. The gas garbage disposer didn’t really catch on, one supposes.

In 1962 Section 4:220 of the city code was amended to address smoke nuisance and burning of rubbish and waste materials.

On August 20, 1962, Councilman Howard asked for an ordinance to eliminate dumps, junk cars, etc.

Public dumping continued: In 1963 citizens were advised that Park Police will strictly enforce the dumping ordinance passed on April 18, including levying a $100 fine.

Also in 1963, a study was called for regarding the need of a refuse disposal dump.

In 1965 the City Council approved a refractory lining construction at the municipal incinerator, to cost $30,795, by the Hilton Fire-Brick Service.

In June 1965, William Terry (owner Daniel Otten) got approval from the City Council to have a continuous burning at the property in the southwest sector of the intersection of Wayzata Blvd. and Hampshire. He could burn for 72 hours, supervised by the fire department, and could not bring anything else on the property to burn.

In 1965 Carl Bolander and Sonns got permission for contractor storage and fill (dump) east of Highway 100 and north of 34th Street.

“Hard ash” from the incinerator (mostly ashes with bottles and cans melted to hard blobs) was being dumped in the Bass Lake area as of 1966.

In 1968 Woodlake Sanitation Service was the designated hauler.

In 1969 a new pollution ordinance was enacted by the City. Garbage haulers needed licenses, and people could no longer burn garbage and leaves. See Environmental Activities. Wood Lake Sanitary Service was the residential hauler. Willie Gall’s Rubbish Removal was a private hauler.

On September 7, 1971, a Ban-the-Can ordinance forbidding the sale of nonreturnable containers was passed by the City Council after heavy lobbying by environmentalists. It was to be effective on September 1, 1972. Grocers objected to the move, and some on the City Council were loathe to take this step before surrounding municipalities did as well. The measure was postponed for three years, then repealed in 1975.

In 1972 Metropolitan Recycling opened a bottle and can Recycling Center at 1st Street NW and Walker Street on the old Creosote property. The director was Tim MacDonald, who said that the center paid for itself after the first year. The two semi trailers were donated by Theodore Hamms and Coca-Cola. The site, which was attended by handicapped personnel, accepted no newspapers or magazines. The Chamber of Commerce and the St. Louis Park Beverage Association built a heated shelter for the attendant. An article in a March 1973 Echo noted that the student group Park Students for Environmental Protection were no longer collecting bottles and cans because of the center, which was opened as a direct result of the group’s efforts. By 1974, the two semis were being filled every 10 days, but in 1975 the center was closed because business wasn’t paying expenses.

Minnesota Soft Drink Recycling opened in St. Louis Park in 1980. It started off slowly, but was picking up by 1982. The Center primarily made money on pop and beer cans – newspaper was recycled pretty much on principle.

The first citywide curbside recycling pickup was on April 16, 1984. A pilot involving 2,200 households had begun in 1982. Collections were made twice a month, at no additional charge to residents. The pilot got state and national coverage because of the high rate (50 percent) that residents used the program, as opposed to the 5-20 percent in Minneapolis. The initial system used three separate containers, which were purchased with Community Development Block Grant funds from HUD. Ours was the first city to achieve curbside recycling. The League of Women Voters worked for eight years to get the program supported. Surrounding communities such as Hopkins, Minnetonka, and Eden Prairie started their curbside programs in 1989.

In 1987 Hennepin County Chairman Mark Andrew named St. Louis Park the leading city (out of 46) in the County for its efforts to recycle glass, paper, cans, and yard waste. The City’s volunteer curbside recycling program encompassed 12,000 homes. Andrew pushed a bill to have a recycling program in every city in the County by January 1, 1988.

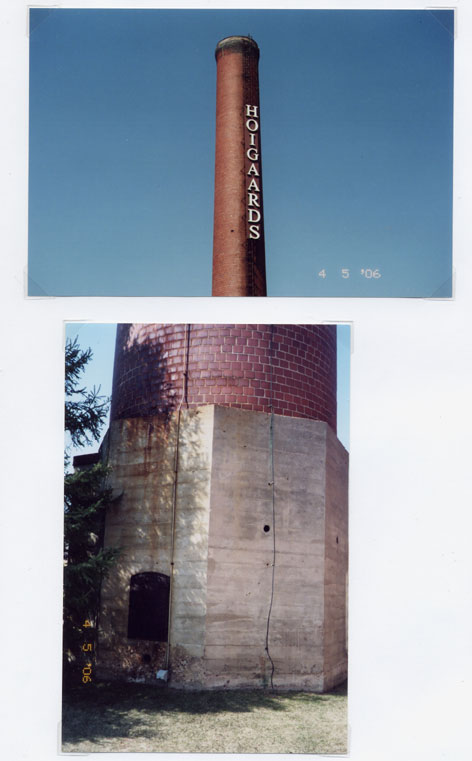

In 1989 the city incinerator was demolished, ending the shower of white ash over the area. Hoigaard’s expanded onto the land, keeping the chimney as an advertising landmark.

In 1989 the collection of newsprint glutted the market and the recycling company Super Cycle went out of business. Local community recycling went on hiatus while local governments worked on creating markets for the recycled materials.

On November 15, 1989, an ad in the Sailor announced “We’re Finally Open!” Minnesota Resources had relocated to 5105 W. 35th Street (aka 5100 W. 36th St.) in the Beltline Industrial Park. The ad was actually a coupon one could use to sell aluminum cans for 5 cents per pound.

The incinerator tower was removed on or about February 14, 2007 to make way for Hoigaard Village.

In 2013 the City began a program to collect household compost. Citizens could voluntarily collect certain kinds of degradable garbage in special bags and put them, along with their yard waste, out in a separate bin on garbage pickup day. Recycling was changed to mixed cans, bottles, and paper, and picked up every other week.

PLASTIC BAG CHRONOLOGY

Here is a chronology of the plastic bag, just because we have it. In 1967, the advice given to Dustin Hoffman was “Plastics.” The development of plastic sandwich bags on a roll (“baggies”) actually happened a decade earlier, in 1957. Plastic dry cleaning bags came around in 1958, and in 1966, produce bags were introduced in grocery stores. Plastic garbage bags first appeared in the late 1960s. And people first had to decide “paper or plastic?” in the mid 1970s. Today, Americans throw 100 billion plastic bags in the garbage – only 0.6 percent are recycled, even though bins are provided at most grocery stores. Cities are slowly moving to ban plastic bags and Styrofoam containers.