HONEYWELL

The following information was provided by veteran activist Marv Davidov via brochures and other information he provided during an in-person interview prior to 2007.

Honeywell International was started by inventor Albert Butz, who developed a “damper flapper,” a prototype thermostat. A series of mergers and acquisitions followed, and the company became known mostly for its controls and regulators. Their biggest contribution was the “Honeywell T-86 Round,” a type of thermostat invented in 1953 and found in most homes in America.

During the Vietnam War, Honeywell was the largest military contractor in Minnesota, and had sales offices and plants all over the world. It was one of the top 20 arms manufacturers. An Ordnance journal quoted an ad: “We stand ready to build weapons that work, to build them fast and to build them in quantity.” The company’s headquarters was at E 28th Street and 5th Ave. So. in Minneapolis.

CLUSTER BOMBS

The source of much protest was the manufacture of Cluster Bomb Units (CBUs). These were “globes full of BB-like projectiles that would spread over a large area when the globe impacted, tearing human beings to pieces but no harming property. The anti-personnel bomb was used primarily to terrorize and intimidate civilians, and may have been responsible for the death and maiming of more non-combatants than any other single weapon.” About 90 million fell on Laos alone, and it is estimated that 10-30 percent of them are still unexploded, occasionally killing more civilians. Millions more fell on Cambodia and Vietnam – North and South.

The bomb was made up of a canister that the Air Force called the “mother bomb.” Inside were 300-500 Bomb Live Units – “Bomblets” – “sisters and daughters” that exploded in mid-air, releasing steel ball bearings that fell at 22 ft/sec. Activists argued that the use of this weapon, which killed and maimed an alarming number of women and children, was against Article 23 of the 1907 Hague Convention with regard to “unnecessary suffering.”

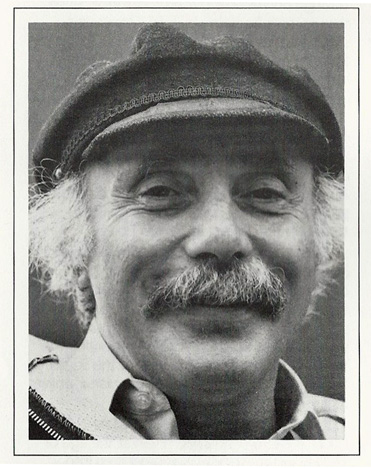

ENTER MARV DAVIDOV

Marvin Allen Davidov was born in Detroit on August 26, 1931. In 1949, at age 18, he moved to the Midway in St. Paul to work at his uncle’s department store and begin classes at Macalester College. In 1950, his parents and brother Jerry joined him. From 1953 to 1955, Marv served in the U.S. Army. He participated in two Freedom Rides in 1961; one to Georgia and one to Jackson, Mississippi. While spending several years in the 1960s in Berkeley, California, he married (May 1966) and divorced (January 1968) Vicki Eskin, a graduate of UCLA. After becoming a seasoned draft resistance organizer, he returned to Minneapolis later in 1968, where he lived until he died.

HONEYWELL PROJECT

Davidov’s new focus was now the founder of the Honeywell Project. The first meeting was held on December 8, 1968, with 25 in attendance. Their purpose was to call attention to the fact that Honeywell was manufacturing weapons that were killing innocent people. Honeywell Project chapters were formed at the U of M and other colleges in the area.

For years during the Vietnam War era, Davidov carried around a deactivated cluster bomb, the size of a softball, to show anyone who would listen that Honeywell was creating weapons being used by the U.S. military. He said the weapons indiscriminately killed innocent civilians in Southeast Asia. Davidov estimated that he was arrested 40 or 50 times, mainly in antiwar and civil rights demonstrations. (Marv’s obituary)

In 1969, Davidov met with Jim Binger, Chairman of Honeywell. Davidov offered to bring people in to convert plants to make peaceful products without a loss of jobs. This idea was not well received, so on April 29, 1969, the first demonstration was held at headquarters, where the group leafleted shareholders at a corporate meeting.

Two weeks later, in May 1969, project activists leafleted the St. Louis Park manufacturing plant, alerting employees of the evils of the product they were making. Demonstrations were usually only held at headquarters, not at plants. There were about 14 plants at the time in the Twin Cities – the plants in St. Louis Park and Hopkins were the main weapons plants. (Davidov)

At a 1969 St. Louis Park city council meeting, citizens requested that zoning law be changed to remove the plant, but this was not considered. (Davidov)

On December 12, 1969, the group leafleted all Honeywell plants in the Twin Cities. Demonstrators picketed Headquarters and then went downtown to leaflet Christmas shoppers. (Davidov)

APRIL 27, 1970 (Monday)

Joe Blade of the Minneapolis Star reported that the chaos that became the riot of April 28, 1970, started as a rally staged the night before at Macalester College. And that really started when several hundred sympathizers greeted every passenger on Jerry Rubin’s plan with cheers when it arrived at MSP Airport. It that enthusiasm continued at a press conference at which pacifist Stewart Meacham removed his coat, tie, and shirt because Rubin had said that people in coats and ties were not brave enough to bring about a peaceful world. Unclear how that’s written whether it was Meacham or Rubin’s coat, tie, and shirt that was removed…

Apparently there was a disconnect between Rubin and his audience, as reporter Blade wrote that Rubin thought Honeywell made Honey, and went on about the capitalist system and his adventures in trying to overthrow the Government, which was not the issue at hand. Then he went on to call the most oppressed people in the country the white, middle-class youth, which neatly fit his audience. They are so oppressed because they are so secure; they must free themselves by becoming “white niggers” by giving up their money and privileges.

Molly Ivins of the Minneapolis Tribune estimated that 3,500 people attended the Monday rally, roaring to their feet as Rubin yelled, “We’re gonna make Honeywell stop makin’ bombs and go back to makin’ honey!” One of the organizers of the Honeywell Project behind him was heard to say, “A little off, but Right On!” Rubin was the last in a series of “rousers at the big yippie-rad-pacifist pep rally” before the big game the next day. (April 28, 1970)

APRIL 28, 1970 (Tuesday)

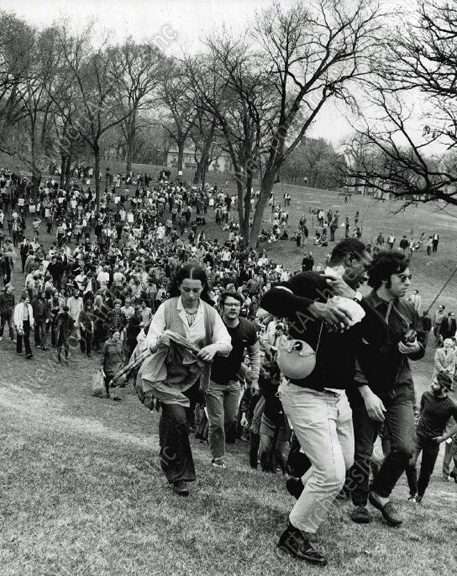

On April 28, 1970, a group of 3,000+ people that included activists Jerry Rubin and Dennis Banks marched from Fair Oaks Park by the Art Institute to Honeywell Headquarters. Although the members of the Honeywell Project were committed to disciplined nonviolence, others in the group, perhaps including paid informants, broke their agreement not to use violence and pushed the door in. The demonstration became a riot of broken windows and mace. (Davidov)

The morning press reported rumors that FBI informants were in the crowd, and that Dennis Banks was telling the crowd that “Nonviolence was hypocrisy and a cop-out.” Rumors flew that the company had planted tear gas around the building and rock-proof glass around its computers. (Richard Gibson, Minneapolis Star, April 28, 1970)

From the Historyapolis Project:

The Honeywell Project used direct action protests and shareholder activism to pressure the company to abandon the development and production of all weapons systems. The Honeywell Project attracted thousands of supporters, who sustained this effort for almost twenty years, through the end of the Cold War.

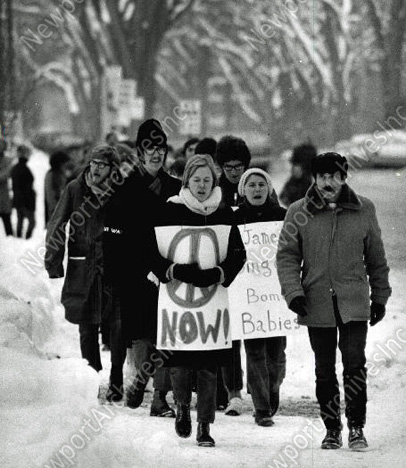

The photo below shows marchers carrying proxies as they converged on the 1970 Honeywell shareholder meeting. They were demanding the right to speak at the meeting about the role the company was playing in the Vietnam War. Taken by a Star Tribune photographer, this image is held in the collections of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The protesters were met with police resistance, and there was violence on both sides. Demonstrators tussled with a glass door, eventually breaking it and sending broken glass all over secretaries and into a Honeywell usher’s forehead. The usher was also hit by Mace. A Honeywell Security Guard pinched his hand in a door and also had slight rib bruises. A demonstrator received leg wounds. One 24-year-old demonstrator was arrested. (Minneapolis Star, April 29, 1970)

Stephen Hartgen of the Minneapolis Star described the scene this way: (April 29)

- Beer bottles tossed through plate glass doors

- A Security Guard lying prone in the corridor building, holding his Maced eyes with a wet handkerchief

- A police detective roughed up by youthful demonstrators

- All this blended with a constant din of obscenities and shouts like “All Power to the People!” and “Up Yours, Honeywell!”

- Youths, bare chested with painted peace symbols, and flowing hair pulled back with leather thongs

Honeywell Board Chairman James H. Binger had put restrictions on how many stockholders could attend the meeting, which raised questions about whether the meeting was being held in conjunction with Robert’s Rules of Order. He was so mad that he cut the meeting off after only 14 minutes. (Minneapolis Tribune, April 29, 1970) He was persuaded to call off the police, in which case Davidov was able to persuade the demonstrators to go back to the rally at the park.

The Honeywell Project did organize some protests in the early 1970s, but the movement collapsed with end of Vietnam War in 1975. The group fell apart and got back together twice during the 1970s. Honeywell scaled down too: arms had been up to 20 percent of the company’s business, and with the end of the war, 50,000 jobs were eliminated worldwide. (Davidov)

All along the group suspected that they had been infiltrated by the FBI, and in 1977, the ACLU sued Honeywell and the FBI for the release of documents regarding surveillance of antiwar activities. The FBI was ordered to provide names of paid informants who infiltrated the Honeywell Project from 1969-1972. In August 1984, a Federal judge ordered the FBI to disclose the names of those hired to spy on the Honeywell Project and other groups. The suit was settled in 1985 when Honeywell and the FBI paid $70,000 to the Honeywell Project. (Davidov)

The protests would snowball over the next two decades, culminating in mass arrests in the early 1980s, when the project was robust enough to support an office at 3144 10th Avenue South and a small paid staff. One of the women repeatedly arrested was Erica Bouza, the wife of police chief Anthony Bouza. (Minneapolis Project)

- In June 1981 vigils were held at Honeywell Plaza.

- In June 1982, the group protested Honeywell’s manufacture of cluster bombs that were used by Israeli forces shelling Beirut.

- In November 1982, the group, including Daniel Berrigan, padlocked and barricaded Headquarters. 36 people were arrested.

- On April 18, 1983 there was another blockade, this time attended by Phillip Berrigan. 151 people were arrested, including Erica Bouza, wife of Minneapolis police chief Tony Bouza.

- At an October 24, 1983 demonstration at Headquarters, 577 were arrested, including a young Honeywell engineer who quit his job to join the protest.

- 15 people were arrested at a December 28, 1983 demonstration.

- On April 27, 1984, 284 arrests were made.

- 135 were arrested on May 16, 1985.

- 48 were arrested on November 4, 1985.

- On October 2, 1985, HP protested the use of Honeywell-manufactured weapons and components used in US attacks on Libya. The Gandhi’s Birthday party yielded 98 arrests out of 300 participants.

- Arrests were made at the April 21, 1988 action to block Orchestra hall, site of the Honeywell annual meeting.

From 1982 – 1989, about 2,200 people had been arrested at these protests, and had served a combined two years in jail. Davidov himself was arrested 25 times, and sentenced to jail three times.

THE END OF HONEYWELL WAR TECHNOLOGIES

In 1990, Honeywell spun off its defense and marine systems contracts into Alliant Tech Systems, Inc., a separate corporation. (Minneapolis Star Tribune, February 21, 2010) Davidov’s take was that the Honeywell Project was a major factor in the decision.

The building that had housed the St. Louis Park plant was demolished in 1996. Honeywell had to remediate the mercury that was used in bomb fuses.

Alliant Tech Systems was later sued by Alliant Computer Systems Corp. in a trademark suit. In December 1990, Alliant Tech lost, and had to take back the Honeywell name, but the two companies stayed separate. (Minneapolis Star Tribune, February 21, 2010)

In 1991, the Honeywell Project disbanded for good. (Davidov)

In 2010, Davidov and Carol Masters published a auto/biography of his life called You Can’t Do That, published by Nodin Books.

Marv Davidov died on January 14, 2012, at the age of 80.