A SUMMARY OF WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE IN MINNESOTA

Online sources for this section include MNOPEDIA’S article by Eric W. Weber and the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library.

In 1875, the Minnesota constitution was amended to provide that “Any woman at the age of twenty-one years and upward, may vote at any election held for the purpose of choosing any officers of schools, or upon any measure relating to schools, and may also provide that any such woman shall be eligible to hold any office pertaining solely to the management of schools.”

However, two years later a bid to allow women to vote on matters of prohibition was unsuccessful, and the law was further clarified that women could only vote for school board officials and no local officials.

Seeing the need for a statewide agency, 14 women formed the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA) in Hastings in 1881. Among the founders were Harriet Bishop and Sarah Burger Stearns. Stearns became the organization’s first president. By 1882, the MWSA had grown to 200 members.

In October 1885, MWSA president Martha Ripley convinced the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) to hold its annual meeting in Minneapolis. This national event demonstrated the importance of the MWSA. It also drew the attention of Minnesota’s male lawmakers. The MWSA eventually became a chapter of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), which formed in 1890.

In 1893, the MWSA convinced the Minnesota Senate to take up women’s suffrage. President Julia Bullard Nelson worked with Ignatius Donnelly, a Populist state senator. The Populists regularly supported a women’s suffrage plank. Nelson herself was a Populist school superintendent candidate in 1894. Nelson and Donnelly initially sought the vote for women in municipal elections. However, the Senate went further. Its members voted to remove the word “male” from the state’s voting requirements. The bill passed 32-19. However, this change did not pass the House. That chamber did not have time to take it up before the legislative session ended. Even if it had passed the House, however, the voters of Minnesota would have had to approve it before it became law.

After the failure of the 1893 amendment, the MWSA was unable to build on its earlier success. The MWSA and its ally, the Political Equality Club, placed women’s suffrage before the state legislature every session. Each time, the bill either died in committee or was defeated.

As the national movement for suffrage gained strength, so did Minnesota’s movement for suffrage. Minnesota suffragists began to use new tactics such as parades, rallies, advertising, and promotional tours in newly purchased automobiles. They even had female stunt pilots put on aerial shows in support of suffrage. Clara Ueland served as MWSA President from 1914-1919, when the suffrage campaign in Minnesota gained significant momentum. On May 2, 1914, she organized a parade of over 2,000 suffrage supporters through the streets of Minneapolis, giving the movement renewed attention.

Other prominent organizers for suffrage in Minnesota included Ethel Edgerton Hurd, Emily Haskell Bright, Bertha Berglin Moller, Emily Gilman Noyes, and Nellie Griswold Francis. For more information about these women, see Minnesota History, Fall, 1995, p. 291-303.

By 1919, 30,000 women across the state officially belonged to local suffrage associations such as the MWSA and the NWP. Their numbers and continued activities convinced lawmakers to act. On March 24, 1919, before the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, the Minnesota Legislature passed a law allowing women to vote for presidential electors. On August 18, 1919, the U.S. Congress legislature passed legislation authorizing the 19th Amendment, which allowed women to vote in Presidential elections. Minnesota was the 15th State to ratify the amendment, on September 8, 1919. The Amendment took effect in June 1920 when the last of the required two-thirds of the states approved it.

With their right to vote secured, the MWSA became the Minnesota League of Women of Voters in 1920, with Clara Ueland as president.

NOTE: Although suffrage granted all female citizens in the United States the right to vote, certain populations were not allowed to become full citizens, which denied the women of these populations the right to vote. For example, Native Americans were not granted citizenship until the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. And despite passage of that law, states still could decide whether or not Native Americans could vote.

FORMATION OF THE SLP LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS

The St. Louis Park League of Women Voters was started in the Fall of 1953 when 18 members of Unit 45 of the Minneapolis LWV who lived in the Park held a pre-organizational meeting on September 9 at the Village Hall. The meeting was chaired by a Mrs. Dosse, who “made it clear that while Minneapolis is not eager to divorce its suburban units, it does not intend to encourage any further violations of National Policy.” (Two other Minneapolis units made up of Park residents chose not to participate in the new SLP League.) A pre-organizational was held on October 27. On November 17, 1953, 52 women attended the organizational meeting at Lenox School, and officers of the Provisional League of Women Voters of St. Louis Park were elected. Mrs. Ernest Marotta (Bunny) was elected the first president. The first general membership meeting was held at Village Hall on December 10, 1953. The group was officially chartered on July 10, 1954, with Mrs. William Bierne as President. Its 134 members met in 11 units.

MISSION

The League of Women Voters, a nonpartisan political organization, encourages informed and active participation in government, works to increase understanding of major public policy issues and influences public policy through education and advocacy.

NONPARTISANSHIP

The League supports or opposes governmental issues which members have studied and reached agreement upon. It does not support or oppose political parties or candidates. As individuals, members are free to be active in party politics, and are encouraged to do so, except when they represent the League in the public eye.

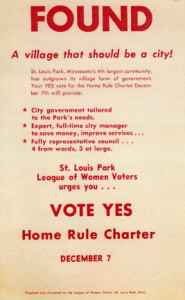

THE FIGHT FOR THE CHARTER

In September 1954, the League focused on a study of the proposed St. Louis Park Home Rule Charter, and they campaigned vigorously for the passage of the Charter. Two previous referenda had turned down the new form of government. The League held meetings in their homes for friends and family, provided public speakers for 24 meetings of local organizations, campaigned by telephone, advertised in the Minneapolis and St. Louis Park newspapers, and distributed 10,000 fliers door to door. The Charter was passed on December 7, 1954, and Charter Commission Chairman Everett Drake said “The effort put forth by the League of Women Voters was the greatest single factor in bringing about the overwhelming adoption of our new City Charter.”

KNOW YOUR CITY

One of the first activities undertaken was the local government survey. Leaguers attended meetings of the Village Council, School Board, and others; researched news articles; read past minutes of governing bodies, interviewed local officials, etc. They strove to collect information on the history, economics, and physical characteristics of the Village. Organizations, churches, and schools were listed as well. The study was called “Surveying the Park,” and it was issued in May 1954.

In November 1955 members Mrs. Ernest Marrotta, Mrs. Herbert Ramberg, and Mrs. Elwyn Williams prepared the first “Know Your City” handbook, setting forth the important facts about the city government. The booklet was based on the original “Surveying the Park” that was issued in 1954. Sources of new material for the study were the home rule charter, the City’s administrative code, and the annual budget for 1956. This booklet was updated and published for several years before the City took over the responsibility (see Community Handbook below).

VOTER REGISTRATION

In 1955 City Clerk Joe Justad deputized League members so they could register citizens to vote. This was to be a core activity for the League throughout the years, and was one of the first efforts of this kind in Minnesota. Booths were set up in shopping centers around the City. When 18-year-olds were given the vote in 1971, booths were set up at the High School to register new voters.

OTHER ISSUES

The issues the League tackled over the years cover every aspect of Park life. These include:

-

the City plan

-

the City parks and recreation bond issue of 1958

-

the SLP Library

-

the school bond issue of 1965

-

straw polls of issues at a booth at Robin Hood Days

-

law enforcement

-

bike trails

-

affordable housing

-

zoning

-

nuisance control

-

education

-

juvenile justice

-

energy

-

community education

-

reproductive choice

-

disability rights

-

the Equal Rights Amendment

-

foreign affairs

-

mental health

-

firearms

-

domestic abuse

-

cultural diversity

-

desegregation

-

immigration

-

air and water quality

-

clean indoor air.

Leaguers sit in on City Council, School Board, and other meetings as observers, and they sponsor candidates meetings before elections.

EMPTY BOWLS

In 2002 Dorothy Karlson, a member of League of Women Voters, became the chair of Empty Bowls. She presented to the League Board the importance of supporting this event whose purpose was to bring financial support to STEP (St. Louis Park Emergency Program) and to thank the community of its ongoing support of this vital organization. The board immediately offered to help by giving a donation and becoming a sponsor. Every year since then League members have volunteered at the donation tables on the day of the event. This is just one example of the way Leaguers view their role of doing everything possible to meet the needs of St. Louis Park residents.

COMMUNITY HANDBOOK

In 1993 League of Women Voters St Louis Park (LWV SLP) decided to find out if St. Louis Park really was a welcoming community. It was found that the two most common barriers for the new residents were transportation and communication. There were many services available, but it appeared difficult to find out about them. A committee was formed and all community resources including schools, churches, and community organizations were contacted. The results were printed in a book called “Feasibility of a One-Stop-Shop for Family Services.” The book was widely distributed. It was hoped that one day the old Central Junior High would become a center for many community services and information would be offered as to where help was available.

The idea of a one-stop-shop never materialized, but the information in the book proved useful. However, to carry the idea even further, LWV SLP decided to create a “New Neighbors’ Handbook” that would contain information about how to get help in an emergency, where to find things, educational opportunities, and more.

A committee of leaguers was formed and the handbook was created. It contained names and phone numbers of resources available and also gave important information in the form of “Good to Know” paragraphs.

The book was translated into three other languages (Somali, Spanish, and Russian) and was distributed widely throughout the area. Eventually the city took over the printing and distribution of the handbook. Martha McDonnell, a St. Louis Park city employee, became responsible for seeing that enough copies were available.

With the passage of time, the city requested that the handbook be updated. Another committee was formed to make the book more current. Elaine White, Eilseen Knisely, Ellen Hacker, Barb Person, and Dorothy Karlson formed this committee and called each phone number in the book to confirm that the information was correct. Email addresses and web sites were added.

When the book was near completion it was discovered that the St. Louis Park School District had found that information about services available in the city was lacking. Teachers needed a way to inform parents about additional services. As part of their strategic plan, the school district decided to further develop the handbook. Linda Savaraid, Director of Community Education, was put in charge of the project.

Ms. Savaraid was able to bring valuable additions to the handbook. A local graphic artist, Kelli Burrows, who designed the original “New Neighbors’ Handbook,” was hired to design the updated booklet. She also agreed to create a website for the handbook and maintain it for two years.

The new black and orange handbook entitled “St Louis Park Community Resource Directory” came into being and was available in schools, apartment complexes, and community buildings beginning in the fall of 2010. Mary O’Brien took over the project when Linda Savaraid left the district.

The Family Services Collaborative approved $4,000 to print and distribute 5,000 copies that went to school and city employees, boards and councils, faith communities, non-profit organizations, and health care organizations.

The next step was to develop a web site for the Family Services Collaborative that would host the community resource directory. Once again the Collaborative offered a grant of $2,200 to make this happen. A plan was put into place to update the Directory. As a result, the Directory is available on-line offering current information to St Louis Park residents.

What started as a question about whether St. Louis Park is a welcoming community developed into the answer that our community continues to thrive. It helps fill the gap that was found in regard to communicating the availability of services and it happened because of the collaboration of the LWV SLP, Community Education, and the SLP School District.

PRESIDENTS OF THE LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS OF ST. LOUIS PARK

It is interesting to note that, despite the empowering nature of the organization, in the beginning members were identified by their husbands’ first names, with the women’s names in parentheses. It is significant that this practice changed in the pivotal year for women’s rights, 1972, when the husband’s names were shown in parentheses.

Click Here for a pdf file of the Presidents.