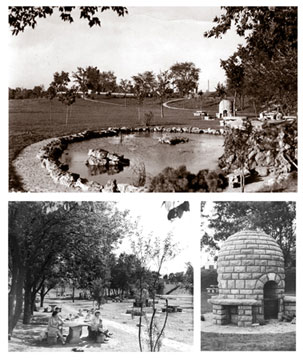

All but gone now, the roadside parks of Highway 100 were nothing less than a phenomenon – so much so that families came out to the highway just for the ride and the opportunity to picnic among the lilacs. The furniture was stone, and the three-family barbeque grills took the name “beehives.”

But the Highway 100 of 1939 is no match for the needs of the new millennium, and most of the parks had to be sacrificed. The only park now in St. Louis Park is the newly-renamed Lilac Park, (formerly called St. Louis Park Roadside Park) at Highway 7. This park has been extensively renovated, and the “Beehive” fireplace from the park at Minnetonka Blvd. is now the focal point of Lilac Park. The St. Louis Park Historical Society has worked with officials from the City, Mn/DOT, the State Historic Preservation Office, and Three Rivers Park District to move and restore the Beehive and renovate the new Lilac Park. We feel that it was important to preserve this piece of our history.

This chapter celebrates these much-loved roadside retreats. A great deal of the following material was provided by the people at Mn/DOT, who appreciate the historical value of these parks and safeguard their historical records. A major resource is the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) prepared by Mn/DOT in the 1990s.

First we explore the foundation of the roadside park movement, using Americans on the Road: From Autocamp to Motel, 1910-1945 by Warren James Belasco as a resource. We also provide a timeline of the creation of Highway 100’s parks, with a section on parks designer Arthur Nichols.

At the end of this page are links to individual pages on each of Highway 100’s Roadside Parks.

TIMELINE OF MINNESOTA’S ROADSIDE PARKS

As automobiles became affordable, families traveled for pleasure, often for days at a time. Lacking modern conveniences, travelers often imposed on farmers for water, restrooms, and even food. Belasco wrote:

Many rural areas had had enough. Roadsides were strewn with garbage, especially with tin cans, the autocamper’s emblem.. tourists broke off fruit tree branches to decorate their cars or graft at home, picked flowers, corn, apples, and even milked the cows. Schoolyards, a popular camping spot, were left a mess.

1929

Minnesota started to “preserve native trees along the roads wherever possible,” and paid more attention to the aesthetics of the roadside while building highways.

1930s

The State began to regulate tourist camps.

1932

The State established the Roadside Development Division of the Minnesota Department of Highways, headed by Harold E. Olson. Arthur R. Nichols acted as the consulting landscape architect (see below). The Division’s principal objective was to increase the recreational qualities and public enjoyment of the state’s highways. The earliest roads had been laid out by engineers who had been trained to lay out railroads, and many of those roads were precarious for automobile traffic. Instead of fixing those roads, the Division chose to start over, using principles of highway planning, conservation, and providing a “natural transition between construction and nature.”

A Conference on Roadside Development was held, attended by Minnesota groups organized to lobby the State for roadside improvements.

The Emergency Relief and Construction Act provided Federal funds to states for direct relief and job creation. Programs could not compete with private industry, and had to do work that “would not otherwise be done,” which includes all of what we have come to know as public works projects.

1935

Construction on Highway 100 began. See the chapter on Highway 100 for details on the construction of the highway, including the story of Lilac Way. Construction was principally completed in 1939, but not entirely finished until 1941.

1937

Federal legislation required that at least one half of one percent of federal allotments for trunk roads be used for roadside improvements.

1938

At least 1 percent of Federal highway allocations was required to be used for roadside improvements. This requirement was dropped in 1946, although Minnesota continued to fund roadside development.

In its Annual Report of the Accomplishments of the Roadside Development Division, the Minnesota Highway Department stated:

Stopping points have been provided for the traveling public along the Belt Line where they may stop to enjoy the scenery or picnic. These roadside parking areas are equipped with tables, fireplaces, drinking fountains or wells and are situated at strategic points along the Belt Line where right of way widths made possible such a development.

1939

Highway 100’s Roadside Parks were built. These parks were designed by the Minnesota Central Design Office of the National Park Service and Arthur Nichols. Nichols adhered to the National Park Service’s “Rustic” style of architecture and landscape design, which required native materials to be used and for structures to look like they were roughly hand made rather than manufactured. These principles can be seen in the picnic tables and other structures in Highway 100’s Roadside Parks. The stone structures were fashioned by unemployed masons out of limestone cut along the Minnesota River near the Mendota Bridge. Construction of this type required a lot of skilled labor, and when the war came, the style was no longer feasible. Many of the parks were constructed on parcels of land that the State had acquired along with the right-of-way for the highway.

ARTHUR NICHOLS

Arthur R. Nichols became the Roadside Development Division’s Consulting Landscape Architect in 1932. Already age 52, Nichols remained with the Division until 1940. He had trained in engineering and highway design as well as landscape architecture at MIT. From 1902 to 1909, Nichols and Anthony Morell worked for a landscape architect that designed sites around the country. In 1909, the two formed Morell and Nichols and set up shop in the Architects and Engineers Building in downtown Minneapolis. The firm developed master plans for cities, subdivisions, college campuses, private estates, public properties, and the University of Minnesota. It was also consultant to the State for the design of the State Capitol Approach, and designed part of Lakewood Cemetery. Partner Anthony Morell died in 1927. Nichols died in 1970.

DESCRIPTIONS OF HIGHWAY 100’S ROADSIDE PARKS

Excelsior Blvd. Roadside Parking Area

St. Louis Park Roadside Park – now renamed Lilac Park (at Highway 7)

Old Lilac Park (at Minnetonka Blvd.)

Glenwood Ave. Roadside Parking Area (Golden Valley)