Was Highway 100 an old Indian path or oxcart route? Did the pioneers carve it out of the wilderness in the 1850s? Although the answer may not be as romantic, the history of Highway 100 is just as interesting.

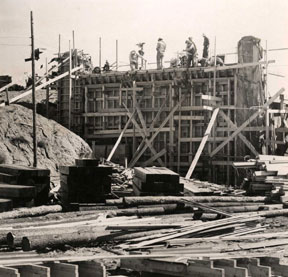

In fact, Highway 100 (i.e., the section north of Excelsior Blvd.) was wrested from the earth by unemployed men of the Depression in the 1930s, as a part of joint project of the Minnesota Highway Department and the Works Progress Administration. Its purpose was as much to provide work for desperately poor men during the Depression as it was to facilitate transportation in the western suburbs.

In addition, it was designed as a destination in and of itself, dotted with roadside parks where families could pull off the road and have picnics. See Highway 100’s Roadside Parks for that part of the story.

Also see: Video on the Creation of Lilac Way

A NOTE ABOUT NOMENCLATURE

The history of “Highway 100” is a little confusing, because it can either mean:

- The Original Highway 100, which was built between 1934 and 1941 along 12.5 miles between Highway 5 (78th Street) in Edina and Highway 52 (now Highway 81) in Robbinsdale;

- The Present Highway 100, which runs from I-494 to I-694; or

- The “Belt Line,” which was a precursor to the present 494/694 circle around the Twin Cities. This Belt Line, of which the Original and Present Highways 100 were a part of, existed from 1950 to 1965.

These are totally different things, and we will be careful to use precise language when describing the building of this highway. Our focus, however, will be on the Original Highway 100, as it passed completely through St. Louis Park.

CARL GRAESER

The story of Highway 100 starts with the individual primarily responsible for building it: Chief Engineer Carl Frederick Graeser (1875-1944). Acknowledged as the “Father of the Belt Line” in his newspaper obituary, he promoted the idea for such a road patterned after the German autobahns.

Described as a “one-legged German engineer,” Graeser came to the U.S. to avoid serving in WWI. He was quite a sight with his wooden leg, German accent, and the black German Shepherd dog that was his constant companion (first named Blitz, then Jet, who accompanied his master to important meetings). A mysterious relationship with a woman in Edina emerged when his will was read. He reportedly died of a heart attack while driving in Robbinsdale.

Central to Graeser’s design were grade separations at major intersections and railroad crossings, cloverleaf connections, and the opportunity to provide numerous entries into Minneapolis via various urban arteries. Graeser had originally planned for a wider median but was ordered to cut them down.

The land was swampy, and during the Depression people were known to cut peat to burn for fuel. The area was so deserted that the first travelers worried about breaking down because there was virtually nothing by the side of the road and very few other cars. In the late 1930s and early ’40s, traffic was so light that it could be shut down entirely for annual parades held in Golden Valley around Decoration Day. The Golden Valley Historical Society has copies of home movies of these parades, taken by local residents, including Mr. Brown of Brown Photo.

There are a couple of stories about Graeser that may or may not be true. One is that he got into an argument with a representative from Edina, and as a result, Edina got no roadside parks. Another is that he requested free water from St. Louis Park during construction, but was refused, resulting in the elimination of a Highway 100/Excelsior Blvd. separation. That had to wait 30 years.

Also see a memoir of Graeser written by the son of one of his engineers, Bernard Thomas Johnson.

LILAC WAY

The highway department did not, as a rule, plant flowers or shrubs along highways, preferring to reserve or restore native trees or shrubbery. The idea was taken up by the Minneapolis Journal, which was credited for coining the term “Lilac Way,” and pushed hard for the plan, likening the rows of lilacs to the cherry blossoms of Washington, DC. (and noting that lilacs bloom for 30 days as opposed to 10 days for cherry and apple trees). An exception was made because “we do not have a rural highway,” but open land.

The fledgling Golden Valley Garden Club promoted the concept of Lilac Way by selling lilac plants door-to-door for the GV stretch of the Original Highway 100. The project was first only intended to range from Glenwood Avenue and Golden Valley Road. The Garden Club sold French lilac bushes (15 cents) and peony roots to pay for those plantings. (Golden Valley Garden Club hint: pound lilac stems with a hammer to make them stay fresher longer in water.) The lilac was adopted as the official flower of Golden Valley.

Arthur R. Nichols was the Landscape Architect who designed the roadway and supervised its execution. Lilac bushes were laid out irregularly, separated by open space and set out against a backdrop of evergreens, elms, other trees and grassy slopes to fit the planting to the natural topography. The completed work included more than 7,000 bushes of 12 varieties of lilacs and thousands of other shrubs, vines, and trees. Along the entire route, trees as large as eight inches in diameter were moved as far as two miles and replanted by the roadside.

In 1938, state highway engineer N. W. Elsberg asserted that the new section of highway was not only safer than earlier roads in the state, but nothing less than “one of the most beautiful in the world” (Minneapolis Journal, January 30, 1938). The roadway design, which included four traffic lanes, adjacent parking lanes and service roads, and state-of-the-art cloverleaf grade separations, epitomized the latest standards for safe and efficient movement of vehicles around metropolitan areas.

The segment of the Belt Line north of Highway 81 has significantly different landscape features, representing the post-World War II construction campaign that completed the Belt Line. Although this northern section retains original plantings, they are primarily evergreens and shade trees instead of lilacs. Any lilacs originally planted in this area were largely removed for highway improvements at Brooklyn Boulevard and construction of Brookdale Shopping Mall. In 2001, 200 lilac bushes were moved from the Robbinsdale stretch of road, which was being widened, three miles north to Brooklyn Center. Mn/DOT and the City of Brooklyn Center share responsibility for moving and maintaining the new site.

The project also included a series of roadside parks or picnic areas. St. Louis Park had three of these parks, at Excelsior Blvd., Minnetonka Blvd., and Highway 7. The parks featured picnic tables, two “beehive” barbeques, rock gardens, and reflecting pools made of limestone quarried near the Mendota Bridge and built by unemployed masons. See Highway 100’s Roadside Parks.

HIGHWAY 100 TIMELINE

1907

The plat of Brookside (west side of 100) was recorded, and owner Suburban Homes advertised in the Minneapolis paper that it was a “creekside garden spot.” It may have been at this time that the name Aurora Ave. was attached to the road.

1909

The plat of Browndale Park (east side of the road) was approved by the Village Council with the proviso that Aurora Ave. be 30 ft. wide instead of 20.

1914

In May the streets of Browndale were approved to be “turnpiked,” on condition that Aurora Ave. be turnpiked a distance of about 500 ft. or to the hill. Not sure what this means.

What was Highway 100 north of Excelsior before the the highway was built? 1914 and 1926 atlases tell the tale. The new road cut through several (mostly truck) farms, effectively putting them out of business. Only two extant roads appear: One was between approximately 34th Street and Minnetonka Blvd., called Vera Cruz. (In 1893 August Johnson owned the land along Minnetonka Blvd. between Toledo and Vernon, south to 32nd Street.) Then, between 26th and 28th Streets, the road was called Birchwood.

There were different subdivisions, sections, and even meridians on either side of the would-be Highway 100 line, so the areas on either side were developed independent of each other and have very different histories. By 1926 one could drive north from Excelsior by a circuitous route as far as Cedar Street [26th Street], but there was no need to go any farther, since your objective was probably east to downtown Minneapolis via Excelsior Blvd. or Minnetonka Blvd./Lake Street.

The route went through two gravel pits (Kline) in St. Louis Park, north through the Held farm, intersecting with Highway 12 at the first cloverleaf built in the Cities. The 1914 map shows a Virginia Lake where the 100/394 interchange is today.

The Golden Valley stretch roughly followed part of old Turners Crossroad. Here it continued northward to Robbinsdale, sometimes following extant roads, sometimes cutting through new territory.

1915

The Tingdale Bros. platted Browndale, named after H.F. Brown’s 77-acre farm, on June 9, 1915. This was on the east side of Aurora Ave. For the most part, these 40 ft. lots were not built upon until after WWII, and would be removed in the 1960s for highway expansion.

1926

The 1926 map shows some interesting obstacles to building the new road to the north of Excelsior. For one, there was a race track between Minnetonka Blvd. and 31st Street. Further north, between Cedar Lake Road and 16th Street at the northeast corner of the village, was a 9.65-acre plot owned by the E.J. DuPont de Nemowrs Powder Co. So far we have seen no other reference to this company, so we are free to speculate that it might have been a gunpowder factory? There was no directory until 1933, so we don’t know where to look it up.

1927

Trunk Highway 5/Aurora Avenue/Highway 169 [later Vernon/Highway 100] was paved by the State in the fall of 1927. The road extended from Excelsior Blvd. 1.77 miles south into Edina. The initial cement road was three lanes – two lanes each way and a “suicide” (passing) lane in the middle. From Excelsior to 50th it mirrored the future Highway 100, but then veered southwest along what is now Vernon Ave. The paving ended at about 53rd Street; today that spot is where the road narrows to one lane each way going southwest. An old name was the Mankato Highway, as it continued southwest to Mankato and beyond. The bridge that took the highway over 44th Street (then the streetcar line and Motor Street) was built in 1927. You couldn’t exit to go to 44th, but a pedestrian could walk down some steps, which had become quite crumbling by the early 1970s when it was replaced.

Bill Clark was three years old at the time, living in a house that is still on Highway 100 just south of Excelsior. Decades later he still remembered that his mother had to tether him to the house because he wanted to wander off and play with the big trucks.

Another family that had lived on Aurora Ave. since the 1920s was the Motzkos. The photo below is of Josephine Nalewaya, sister of Tom Motzko’s wife Rose. She’s standing on the dirt road just before the paving of what at the time was referred to as Aurora Ave. and Highway 169. The big house in the background was 4137 Aurora Ave. and belonged to George Brooks, who owned a gas station at 4400 Excelsior Blvd. The house had to be moved back from the new highway in 1927, and was demolished in 1967.

Below is another Motzko photo. It was taken on July 26, 1927 to document damage to a car after an accident. Supposedly that is Brookside School in the background; at the time the school was only four rooms up and four rooms down, facing what is now 41st Street. What do you think?

1928

On April 5, Carl Graeser appeared before the St. Louis Park Village Council to obtain consent to the plans and specs for Highway 5 [100].

1930

On October 15, 1930, it was noted at the Village Council meeting that in the last five days, there had been five automobile accidents at Highways 5 (to be 100) and 12. (A 1926 map shows that Excelsior Blvd. was known as Highway 12 for a time.) This portends the long history of heavy traffic and danger at this most heavily traveled intersection in the State.

1931

One of the earliest articles published about the highway appeared in the Minneapolis Journal on July 23, 1931. It announced that state and county officials had agreed on plans to construct the “so-called belt line road along its western limits, which was authorized at the last session of the legislature.” Approved was an 11-mile stretch from Robbinsdale to Highway 52. (The route of the original Highway 100 eventually spanned 12.5 miles to 78th Street in Edina.) One of the most important benefits cited was that livestock shipments from the west and north could proceed directly to South St. Paul without passing through either of the Twin Cities.

On August 3, 1931, the Hennepin County Board authorized county highway engineer W.E. Duckett to survey the 100-ft. right of way for the “new belt highway.” The width of the road had been extended from 90 to 100 ft., except in Crystal, Edina, and Robbinsdale.

Joint construction of the Belt Line by the county and state was authorized by the State Legislature. The County was to build the sections south of 50th and north of Wayzata Blvd., with the State responsible for the middle, including the stretch through St. Louis Park. The project was expected to take three years. An official statement promised:

The belt line road would connect every county and town road entering Minneapolis from the west. It will be possible for anyone wishing to enter Minneapolis to follow this road outside of the city until he reaches that part of Minneapolis which he wishes to enter, or he may avoid the city entirely if he wishes to do so. This will relieve those entering Minneapolis from driving long distances.

1932

On April 18, 1932, the Hennepin County board appointed appraisers in connection with the proposed acquisition of land for the highway. The appraisers named were S.W. Batson, Max Hoppenrath, C.G. Wentworth, J.A. Bellmur, John Degnan, and E.J. Goodal.

Carl Graeser presented the Highway Department’s plans for Highways 7 and 100 on July 20, 1932. At the time, Highway 7 was being referred to as Highway 12, and Highway 100 was being referred to as Highway 5.

A 140-ft. right of way for 1.8 miles between 50th and 63rd Streets in Edina, was acquired, graded and graveled. The October 1932 edition of the Country Club Crier described the area under construction as “that portion where it joins Highway No. 5 at the intersection with West 50th Street, south to about West 63rd Street. The route largely follows the Willson Road both as to location and grade except for about a quarter of a mile south of the No. 5 intersection, where the course has been moved west to line up, north and south, with the State highway.” The acquisition of land was done by the County without condemnations. The article describes the project’s southern terminus as the Minnesota River.

1933

A survey of the route was done in 1933 using two crews, one truck, and equipment left over from World War I.

In January 1933, Lake Street businessmen went to court to protest the highway project, fearing that instead of taking Excelsior Blvd. to Minneapolis via Lake Street, they would bypass the Boulevard and take Wayzata Blvd. They were right.

Aurora Ave., south of Excelsior Blvd., was renamed Vernon Ave. in conjunction with a general street renaming effort within the Village. A map shows plans to reconfigure the intersection of Vernon, Excelsior, and Wooddale, since they did not exactly meet up. The map suggests that parts of lots on the east side of Vernon just south of Excelsior were taken even before the highway was built.

The 1933 – 1934 St. Louis Park directory, the first ever, showed that Fred Dean lived at 1800 Quentin Ave., which had been called Quincy before the streets were renamed. Dean’s granddaughter reports that his house had to be moved in preparation for the building of the highway. The house was moved to 1836 Princeton (not an address today) in about 1935.

The Public Works Administration (PWA) was formed in June 1933 and operated until July 1939. Its goal was to provide work to private construction firms, which would in turn hire skilled workers. Unskilled workers were required to be local. To the extent feasible, men, horses, and hand tools would be used instead of heavy machinery, to give the men expanded opportunity to work.

1934

On November 8, 1934, Minnesota received $900,000 in PWA funds in accordance with the National Industrial Recovery Act of June 16, 1933 (the precursor to the NRA). Funds were available to finance up to 30 per cent of the cost of construction equipment and materials.

Funds were provided by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), which had been created in 1933. Projects funded by FERA were referred to as ERA projects, as noted below. In January, the National Recovery Work Relief Program encompassed projects funded under PWA, FERA, WPA, and/or state money, as Highway 100 was.

On April 26, 1934, the Hennepin County Review reported that the project was started by the CWA and paid for by the County, from 36th Ave. No. to Glenwood Ave. Work was abandoned in March 1934 until September 1934. County Engineer W.E. Duckett predicted a year’s delay due to lack of funds.

The State took it over, widened the roadway to 60 feet and provided service roads. It was at this point that it was decided to extend the road to Excelsior Blvd., according to the December 16, 1937, article in the Hennepin County Review.

The County started grading the section of the new highway which ran from Excelsior Blvd. south to 50th Street/Vernon Ave. in Edina. The State later took over construction.

1935

The second phase of the highway was begun between Excelsior Blvd. and Wayzata Blvd.

ERA gave way to the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in January 1935, taking over unfinished projects of the FERA, which ended in June 1935. The WPA provided immediate employment to thousands of construction and landscaping laborers. The Country Club Crier of August 1935 reported that machinery replaced hand picks used in 1934 and the number of Minneapolis applicants was not reduced. Construction was speeded up from 20,000 yards per month to 120,000 yards per month.

4,500 Men’s Bureau clients were given physical examinations, and approximately 3,000 qualified. By 1937, approximately 1,500 men were working on the project every day. As the largest Federal work relief project in the state, the building of the belt line provided an immediate boost to the economy. The WPA operated until July 1939, when it was replaced by the Works Projects Administration (also the WPA) until June 1943. Its biggest year was 1938. In Minnesota, 600,000 people had been employed by the WPA.

Things apparently got off to a rocky start, as the March 2, 1935, meeting minutes of the Village Council included the following:

A letter was received from the Workers Protective Association, relative to the dissatisfaction and friction among the WPA men, and their foreman Mr. Kelley. It is the contention of the Association that this condition was retarding the progress of work. Trustee Jorvig made a motion which was seconded by Mr. Perkins that the Recorder write to Mr. Kristgau for his assistance in handling this matter, and that Mr. Perkins as a committee of one work on this problem. Upon being put to a vote the motion was carried.

An article in the Minneapolis Journal dated May 2, 1935, cited relief authorities, who felt that the project is a “refutation of many of the current criticisms of ERA (emergency relief administration)…” Crews averaging 700 men were at work. FERA had created a Transient Division in July 1933, in an effort to help men who were often turned away by municipalities that only helped their own.

Soon after the relief load became heavy, the Gateway District of Minneapolis developed into one of the sorest of the sore spots. The City’s Skid Row, the district was 25 blocks of bars, flophouses, pawnshops, missions, social service agencies, warehouses, and old office buildings. Hundreds of homeless men were housed and fed in the district, first in hotels, and later, as the load grew, in converted warehouses and factories. Hordes of men roamed streets of the section. Agitators, always sure of audiences there, made the Gateway the starting point of demonstrations. The picture at right is of men passing time at the Gateway, 1937. Photo by John Vachon, from the Library of Congress.

Outbursts of criticism against the standard of relief provided grew louder and more violent, until last fall the public welfare board and the relief department hit on the plan of setting up an ERA project especially for homeless men.

Highway 100 and three smaller projects furnished work for 3,500 homeless men, each working six hours a day for six days [once or twice] per month. [40 hours per month] They earned 55 cents an hour or $19.80 in cash in lieu of the $10.80 they had received in meal and lodging tickets. Frank W. Hooton was the ERA liaison officer. A picture dated July 9, 1935, shows the men boarding a long line of buses after a day of work. Previously they had been transported in open dump trucks.

In July 1935, plans were still in play for a cloverleaf at Excelsior Blvd.; a drawing even showed the proposed motoring marvel, with the intersection looking mighty rural. The Excelsior Blvd. cloverleaf did not come to pass. An article mentioned [Wayzata] Blvd. and Excelsior Blvd., but also stated that the new Highway 7 was carrying the heaviest traffic load in the state, so the switch was logical. At the time, no bridges had been built yet, pending final word on the Federal government’s national grade separation program. The existing road at this point is still referred to as Highway 5, but so was the Fort Snelling-Shakopee Road.

In August 1935, C.M. Stafford of the Saddle and Bridle Club urged that the state add a dirt or tanbark road for the purpose of driving horses: “hackneys with snappy carts,” then a popular occupation. He stated that there were more than 2,500 people who rode or drove horses in Minneapolis. It is interesting to see that horses (or some kind of work animals) were used in the construction of the highway.

In August 1935, Graeser said that the 3.65 mile section from 36th Ave. in Robbinsdale to Wayzata Blvd. would be completed by the end of the month, but funds were still needed for four major bridges. Graeser also warned that unless the WPA immediately allocated $750,000, the project would have to be postponed. He estimated that the $100,000 currently on hand would provide employment for 2,800 men through September, according to a report in the Country Club Crier.

In October 1935 it was reported that the project was held up for several weeks pending its transfer from ERA to WPA. 2,500 relief workers would be given jobs completing the road grading. The highway was expected to be completed in 1936, and the landscaping in 1937.

The first lilac plantings, over 3,500, were made along two miles of highway between Glenwood Ave. and Medicine Lake Road in December 1935.

1936

Farmers along the route lodged a complaint that they were not allowed to hire out their trucks and that Drivers Union No. 574 was preventing them from getting truck hauling jobs through intimidation. Union President William S. Brown denied the charge, and stated that the Farmers’ trucks only had “T” licenses and therefore could not be used for hire. One photo of construction notes that service roads were built along the side of the highway so that farmers would not have to “drive from their farmyards directly into the traffic of the high speed road.”

The Soo Line overpass was constructed at Highway 7. Actually two bridges spaced 10 ft. apart, they are described as “Vaguely Art Moderne in appearance, each pier has a raised vertical panel with streamlined vertical moldings at the center.” These bridges were designed to accommodate two lanes underneath on each side. A notorious bottleneck, in 2006 the road was reconfigured to fit three each until the bridges could be replaced.

1937

For pictures of the construction of Highway 100 from the Minnesota Historical Society, go to http://collections.mnhs.org/visualresources/ and put in Highway 100 as the search term.

On January 1, 1937, the State reported that 3.7 miles between Wayzata Blvd. and Robbinsdale had been graded, representing 1.2 million cubic yards of excavation.

The opening of (one section of) the new Belt Line Highway was celebrated with a picnic in July, sponsored by the Golden Valley Commercial Club. Thousands gathered for sports events, a kangaroo court, and fireworks. The event also celebrated the renaming of Sixth Avenue North as Floyd B. Olson Highway, in honor the Minnesota Governor who died in office in 1936 at the age of 45. Golden Valley also saluted its pioneers.

August 1937: The highway was not complete. However, the Minneapolis Journal reported that work was going to be accelerated so that it could be open between Excelsior Blvd. and Robbinsdale before winter. The State highway department said that the project would definitely be completed by 1938. Two bridges had yet to be built, although the cloverleaf at Wayzata Blvd. was underway. The underpass below the railroad tracks was finished in early August. Now only 400 men were at work on the project.

Snow and Ice in August! ran the headline in 1937:

It was August 30 but these girls found some snow and Patricia, 8, Beverly, 12, and Mary Lou, 9, children of Mr. and Mrs. Neal Doyle, 2618 Toledo Avenue, St. Louis Park, and Gloria, 13, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Elie, 2710 Toledo Avenue, tried to make snowballs. The ice and snow was uncovered by crews working on the new belt line highway near 26th Street and Utica Avenue.

The girls appear to be having a great time with the “Rather muddy snowballs.”

As promised, the cloverleaf at Wayzata Blvd. was ready for business on November 26, 1937 – construction had started on June 20. A December 16, 1937, article in the Hennepin County Review reported that the cloverleaf at Highway 12 (Wayzata Blvd.) was the “Northwest’s first cloverleaf highway grade separation.” The article stated that where such cloverleafs have been built in the east, accident rates were cut sharply. The “belt line” at this point was expected to cost $3 million, intersect nine east-west roads leading to Minneapolis, and traverse 6.7 miles from 36th Ave. N to Excelsior Blvd. It was to be finished in another month, except that the elevation at Highway 7 and the underpass at Minnetonka Blvd. would have to wait until spring of 1938.

Highway 12 was being built with WPA funds. By now the plans for the second cloverleaf had changed from Excelsior Blvd. to Highway 7.

In December 1937, the Highway Department reported that Highway 100 was 80 percent complete.

1938

As of January 1938, the bridges at Highway 7 and Minnetonka Blvd. were the only things to stand in the way of the opening of the new highway. It is now being referred to as Highway 100. An article claimed that an eight-foot sidewalk for pedestrians would border the highway, but that didn’t happen. Fourteen bridges had already been built, including an ornamental concrete bridge over Minnehaha Creek in Edina, and the bridge that went over 44th Street and the streetcar tracks.

As for Excelsior Blvd. (“old” Excelsior Blvd., still), “a center aisle grade separation has been constructed to provide one-way channels in all directions without a stop. A neutral zone is created by a 30-ft. center lane for left hand turns.” Thus was created the most dangerous intersection in the state.

Completion of the highway depended on WPA funding, and such funding was approved in May and again in November.

1939

A report of the Commissioner of Highways dated March 1, 1939, indicates that the Belt Line “is nearing completion.”

The Highway 7 and Minnetonka Blvd. overpasses were completed.

We don’t know exactly when the cloverleaf at Highway 7 was opened, although it can be seen under construction in aerial photos taken in the summer of 1937. The daughter of plumber Clifford J. Browne, President of the St. Louis Park Businessmen’s Association, remembers that her father cut the ribbon for the opening of the Highway 7 cloverleaf. She also remembers riding her bike around the four circles of the cloverleaf that day. The cloverleaf required 30 acres and cost $65,000.

On September 1, 1939, 3M’s Scotchlite product was used on traffic control signage and installed at the cloverleaf.

1941

Work on the Original Highway 100 was completed in 1941. With the onset of World War II, workers and materials were diverted to the war effort.

1946

The Village Clerk was instructed to write to the State asking them to put in lights along 100.

The 1.5 mile portion of the highway between Highway 81 and Brooklyn Blvd. was completed in 1946 – 1947. Mn/DOT does not consider this section part of the Lilac Way Historic District because it was built later, it was not a part of Federal relief construction during the Depression, and it was not adorned with lilacs.

1947

The Dispatch reported that school buses were dropping kids off across the highway from Brookside School and leaving them to their own devices to cross the street. This situation was fixed, but the Village continued to ask the State for a lower speed limit and a stop sign.

By 1947 the road had been extended four miles northeast of Robbinsdale, through Brooklyn Center, to the Mississippi River (including the northern-most segment of Highway 100 project north of Highway 81).

1948

St. Louis Park made a request to the County for funds to buy traffic lights, but County Engineer L.P. Zimmerman reported that there were no funds available. One irate Village Councilman deemed it a “brush off” by the County. The Council made plans to install three lights: Brookside and Excelsior, Ottawa and Minnetonka, and Louisiana and Minnetonka.

1949

The Village Council asked the State to install traffic signals at Highway 100 and Excelsior Blvd.

1950

A traffic light (the second in the Village) was installed at the intersection of 41st Street and Highway 100 at Brookside School. (Plans dated November 19, 1948) Not sure what the first was.

In June 1950, the Village Engineer was instructed to check with the State Highway Department regarding relief from the perennial traffic jam at Highway 100 and Excelsior Blvd.

In August 1950, the Mayor was authorized to sign an agreement with the State for installing a full activated traffic signals at Highway 100 and Excelsior Blvd. A Highway Department map dated October 10, 1950, indicates a reconfiguration of the intersection to accommodate the “Full Traffic Actuated Traffic Signal System.” At this point the road south of Excelsior Blvd. is labeled T.H. 100, 169, and 212.

THE BELT LINE/”HIGHWAY 100″

In 1950, the Highway Department combined new highways and existing roads to form a 66-mile radial route around Minneapolis and St. Paul. For 15 years, this entire Belt Line was also known as Highway 100. The road was especially rough in South St. Paul, where it was comprised mostly of industrial roads. The concept of the Belt Line was lost with the construction of 494/694.

From Wikipedia, a description of the route of the old Belt Line:

- Starting from the current southern terminus [at 494], the Belt Line overlapped eastward with a pre-494 Highway 5 past the Minneapolis-Saint Paul International Airport to its intersection with Highway 55.

- It continued east concurrent with Highway 55 over the Mendota Bridge, then along current Highway 110 through Mendota Heights, then following current I-494 across the Mississippi River and turning north onto Century Avenue in Woodbury, which feeds into current Highway 120 north of Interstate 94.

- It then turned west upon County Road F and north along White Bear Avenue to meet up with and overlapped westward with Highway 96 (the section of which is now turned over to county maintenance).

- It then turned south briefly along U.S. Highway 8 (now a town-maintained street), then carried on westward along the current routing of I-694 to meet back at its current northern terminus.

With the completion of 494/694 in 1965, the “Highway 100” Belt Line fell away. Due to traffic pattern changes over the years, it is no longer possible to directly follow the path of the old Belt Line. Small detours are necessary which involve the use of Exits 40 and 60 of the present I-494/694 freeways.

1951

On one day in July 1951, 20,313 vehicles were counted traveling down Highway 100 north of Excelsior Blvd. At that time the speed limit on Highway 100 was 50 mph.

In November 1951, Edina invited neighboring communities and State Highway Department officials to a meeting about safety issues on Highway 100. Despite requests from the various Mayors, the Highway Department refused to lower speed limits or provide more policemen. The State also refused to provide center dividers, citing Federal steel restrictions.

$515 in damage was done to a traffic signal at Highway 100 and Excelsior, also in November 1951.

1952

Highway 12 was rebuilt as a four lane divided roadway, replacing Wayzata Blvd. as it traversed the northern boundary of St. Louis Park.

In April 1952, the State signed some kind of agreement with the Village for the construction, reconstruction and improvement of Highway 100 with the proviso that the Village allow no gas pumps or billboards along the road and that any parking was parallel only.

A gravel pit located at 2200 Louisiana Ave., owned by the State, was used by the Alexander Construction Co. to pave Highway 100 between Excelsior and Highway 52.

A June 26, 1952, article in the Dispatch outlined a plan to eliminate the at-grade intersection of Cedar Lake Road and Highway 100. The plan was to loop CLR under the Great Northern railway bridge about 300 feet south of the intersection, which had been the source of several deadly accidents. CLR traffic would also use the loop to cross the highway. In the meantime, a two-foot, raised concrete island was built to divide Highway 100 into two two-lane roadways to prevent left-hand turns. This loop still exists today.

1953

In the spring of 1953, the Highway Department began to notify residents on the east side of Highway 100 (south of Excelsior Blvd.) that their houses were in the path of the planned freeway expansion. One man moved into his new house in the fall of 1952, and was told by the State that it was building a highway through it in the spring of ’53. It didn’t get moved until 1967.

In response to the carnage that was being wreaked on the highway, in August 1953 the County closed nine intersections to left turns, including the one at Excelsior Blvd. Residents feared that the highway was becoming a “slaughterhouse.” The State had wanted to shut down all streets crossing Highway 100, but the Village Council protested and the State backed down. Some stretches of road that only had yellow line dividers received concrete barriers to stop the frequent head-on collisions.

As another attempt to reduce accidents, the speed limit on the Belt Line was reduced from 50 mph to 40 in November. In a letter to the Village Council, Mr. C.R. Skanse of 4337 Mackey decried the death traps on the Belt Line and urged no left turns between 50th St. and Robbinsdale.

Cloverleafs were still puzzling to some drivers, and accidents happened. The June 4, 1953, edition of the Minneapolis Star provided explicit instructions on how to negotiate the Highway 7 and Highway 12 cloverleafs. (The Minnetonka Blvd. intersection was not a cloverleaf.)

1954

Citing congestion, in April 1954, Hennepin County Engineer L.P. Zimmerman proposed a “second belt line,” starting with County Road 18 to the west.

A bridge over (new) Cedar Lake Road and the Great Northern Railroad tracks was underway in August 1954. About one mile of Cedar Lake Road was rerouted to the south, under Highway 100, as an “accident prevention measure.” The intersection at “old” Cedar Lake Road was closed.

Click here for a picture from 1954.

1955

Plans for an 80-mile “Super Belt Line” were revealed by Walter Schultz, the Highway Department, and Arthur Overby of the Federal Bureau of Public Roads. The road that would become 494/694 was part of President Eisenhower’s proposed interstate highway network. The first link was to be along 78th Street in Bloomington. Only six miles of 494 would coincide with the present Belt Line (at the end of Highway 100 going east). Plans for I-35 and I-94 were announced at about the same time.

A picture of the newly-constructed Ethel Baston Elementary School shows that the speed limit on at least that stretch of 100 was 40 mph.

In December 1955, complaints were made that drivers were cutting across the berm on the east side of 100 in front of Yngve and Yngve. There were also complaints about dusty conditions south of Excelsior Blvd.

1956

Five more intersections with Highway 100 were closed down, including W. 26th Street and W. 28th Street. Traffic was to be rerouted to the railroad underpass at Cedar Lake Road.

A three-phase traffic signal – allowing for controlled left turns – was installed at Highway 100 and Excelsior Blvd. This in an effort to curb the carnage at the State’s most busy and dangerous intersection.

1958

Locally, hearings were held on the proposed “Super Belt Line and Twin City Freeway system,” i.e., 494/694.

In 1958, City Councilman Torval Jorvig requested that a committee be formed to give Highways 7 and 100 names, presumably like Wayzata Blvd. The committee came up with Centennial Drive (1958 being the centennial of Statehood), and Lilac Way, which it had been called for some time. No action was taken.

1959

E.J. McCubrey of the State Highway Department appeared before the City Council in January 1959 to obtain city approval of plans to widen Highway 100 from Excelsior Blvd. to the Edina city limits. City Councilmen expressed their preference to widen and improve Excelsior Blvd. from France Ave. to Highway 100 instead. Although McCubrey reported this preference to the state, the state’s plan to widen Highway 100 from Excelsior Blvd. to 50th Street in Edina prevailed.

On May 7, 1959, the State Highway Department conducted a public hearing to present its plan to upgrade Highway 100 from I 494 to Excelsior Blvd.

The State Highway Department proposed to reroute Highway 169 right through St. Louis Park. The plan called for the highway to enter the Park from Edina at approx. midway between Brook Lane and Yosemite, cross Brookside Ave. and continue north and west. It would cross Highway 100 at its junction with Wooddale Ave., then cross the Johnson [Wolfe] and Bass Lake areas, and head northwest into Minneapolis.

1960

The Highway Department identified Highway 100 and Excelsior Blvd. as the busiest at-grade intersection in the State. Later statistics show the number of accidents at 40 in 1958 (no fatalities), rising to over 100 in 1964. Bigger cars and crowded roads led to record numbers of traffic accidents that didn’t abate until the gas shortage of the mid 1970s resulted in smaller cars and lower speed limits.

Houses started to move to prepare for the widening of Highway 100 as early at 1960 – a picture of a house being moved down Excelsior Blvd. was printed in the February 2, 1960, issue of the Dispatch.

The City Council authorized an agreement with the State to put up traffic signals at Highway 100 and 36th Street. The City decided to install a temporary signal, to be hand operated by a City employee.

1961

The intersection of 36th Street and Highway 100 was a busy one, and the the City Council allotted $9,000 for a traffic signal to be installed. A hand operated signal was to be used until the permanent one could be installed. The light was replaced by a bridge in 1985.

1962

The Highway Department proposed the “Southwest Diagonal.” The road, later abandoned under a flood of protest led by the Chamber of Commerce, was originally intended to go from downtown Minneapolis to the new town of Jonathan.

“The proposed route… would take Highway 169 on a winding course from a point just north of Excelsior Blvd. on Highway 100, northeast through a major industrial zone [through the site of the Rec Center], across Highway 7 and Lake St. near Chowen Ave., then east of Cedar Lake to a junction with Highway 12 near Penn Ave. Plans call for the rerouting of Highway 7…[which] would mean a probably large but presently undetermined number of homes in Minneapolis would be condemned to make room for the highways.”

In January 1962, the Minneapolis Star reported that Park refused to agree with the plan, and the State Highway Department held up work on upgrading the deadly Excelsior Blvd/Highway 100 intersection. Mayor Wolfe appealed directly to the Governor for relief. In the meantime, only a stoplight regulated traffic at this busy intersection. One businessman suggested erecting a sign at the site: “This congestion due to the courtesy of the Minnesota Highway Department.”

In October 1962, the Highway Department relented and approved plans for an upgraded interchange at Highway 100 and Excelsior Blvd. The State approved a modified diamond-cloverleaf interchange, where 60,000 cars traveled each day. City Fathers were reportedly “jubilant” at the news.

A Highway Department construction plan for grading and concrete surfacing Highway 100 showed the average daily traffic as 28,725-34,900. The estimated daily traffic for the year 1980 was 72,212-87,713. The road was designed for 50 mph (although the speed limit was 40).

1963

After more than five years of discussion and debate, in February 1963 the City Council approved State Highway plans for an improved interchange for Highway 100 and Excelsior Blvd. The plans included a footbridge at 41st Street, to be built in 1967 or 1968. Parents of children who attended Brookside School and Most Holy Trinity petitioned the Highway Department to construct the bridge immediately. The petition effort was organized by Robert J. McFarlin of the Brookside PTA, who stated that the intersection had the highest volume of traffic of any school crossing in Minnesota. Approximately 350 children navigated the crossing every day.

In February 1963, E.J. McCubrey, P.R. Staffeld, and Dean Wenger of the State Highway Dept. presented plans to improve the Highway 100 and Excelsior Blvd. intersection. The City Council approved the tentative plans.

1964

The Highway Department began buying houses on Vernon Ave. south of Excelsior Blvd. to make way for Highway 100 widening project.

In July 1964, the Edina Village Council approved plans for a six-lane divided highway between its northern border south to Highway 62, and a four-lane divided highway to 494 (78th Street). This work included the bridge at 44th Street, and eliminated access to the Highway between Excelsior Blvd. and 50th Street. It also provided long-awaited frontage roads, although it required the removal of four or five houses in Edina.

In September 1964, stop signs were erected at the cross streets between Highway 100 and Wooddale in an attempt to control traffic.

1965

What is now the Present Highway 100 was all that was left of the old Belt Line, according to the 1965 State map. “Old 100” signs were put up, and Highway 100 markers on five highways were removed. Highways 494 and 694 took the Belt Line’s place.

There was still some discussion of the SW Diagonal – see 1962.

Left hand turns on Highway 100 were scary and dangerous. In 1965 the City Council closed the streets on the east side of the highway between 41st and 44th Street. Some were later reopened to right hand turns only. Residents on the west side of the Highway were still able to turn left into their driveways.

1966

In April 1966 the City Council was presented with the full plan for the Southwest Diagonal, still alive after several years.

The Highway Department came to the City Council with a proposal for a bypass for Excelsior Blvd.

1967

After fighting delays by the State Highway Department and cutbacks in Federal funds, the city finally got a commitment to begin work on the Highway 100/Excelsior Blvd. overpass. Work was to begin in the fall. City fathers were jubilant – they claimed there had been more than 100 accidents at the site.

Plans and specs for the Highway 100 expansion was approved, calling for grading, surfacing, bridges, widening the median, and guardrails.

On December 10, 1967, the St. Paul Pioneer Press published a story called “Our Highways are Real Groovy.”

Modifications were made of the ramp and loop terminals at Highway 12.

Work was done on traffic signals and ramp reconstruction at Minnetonka Blvd.

1968

In May 1968, construction began on medians on Highway 100 and the widening of two bridges at Cedar Lake Road and a railroad bridge between Highway 55 and Glenwood Ave. Both steel and Jersey barriers were planned in an attempt to reduce head on collisions.

The SLP City Council approved the final plans for the improvement of Highway 100 in August 1968.

There was still some talk of the SW Diagonal at a City Council meeting in 1968. The plans were holding up the completion of the Highway 100/Excelsior Blvd. underpass.

Between 1968 and 1969, the houses on the east side of the highway, from 41st to 44th Street, were moved or razed. Many (mostly 1939 – 1941) houses were bought for $1 by moving companies and hauled off in the middle of the night, to the excitement of spectators on the west side. Friends were lost and a neighborhood was irrevocably split in half by a road that had once had a stoplight at the corner but could be run across with ease. The photo below was taken in 1968 from 4246 Vernon on the west side, showing two of the doomed houses on the east side.

The photo below was taken in February 1970, showing the land that remained vacant for several years after the homes were removed.

1969

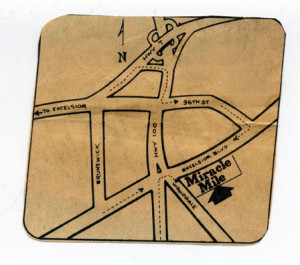

After being held up 6-7 years because of the debate about the Southwest Diagonal, the Highway 100 underpass at Excelsior Blvd. was finally accomplished. A May 1969 ad for Schuler Shoes at Miracle Mile in the Dispatch dared people to find them, given the detour necessitated by the construction:

The bridge was finished in June 1969 (picture in Dispatch July 10, 1969). The ribbon cutting, attended by State Senator Ken Wolfe, Maid Marian Joy Sheekanoff, and Mayor Len Thiel, was held on August 6, 1969. The interchange cost $2.27 million and took two years to complete. At the time it carried 70,000 cars per day, which was projected to climb to 112,500 per day in 1985.

1972

Highway 100 was widened between 44th Street and Highway 7 from four lanes to six. The narrow railroad bridges prevented further widening north of Highway 7. A service road, which retained the name Vernon Ave., was built between 41st and 44th Street to serve homes on the west side of the highway. On the east side, Vernon Avenue continued from part of 41st Street to Excelsior Blvd.

Gordon Andersen, who built his house right on the highway in 1961, photographed the progress of the construction in 1972.

Above: View from the footbridge at Brookside School facing south. The lanes on the right are the original four lanes, and those on the left are the new northbound lanes built where houses used to sit.

Above: This photo, also looking south, shows the complicated rerouting that was frequently done to keep the highway open during construction. Constantly changing traffic patterns caused many accidents, sometimes fatal.

Paving the southbound lanes, August 8, 1972. The old southbound lanes would become a service road.

The intersection of Highway 100 and 36th Street was quickly becoming the most dangerous intersection in the city, particularly when the Rec Center was open. City officials were back to trying to get the State to act. Finally a foot bridge was built, but not until about 1975. Some remember a wooden vehicle bridge.

1976

The Minnesota Highway Department became the Minnesota Department of Transportation (Mn/DOT).

A bridge with half-diamond ramps was built at Benton Ave. in Edina.

1984

Wooddale Ave. between 39th Street and Excelsior Blvd. was renamed Park Center Blvd. This street had also been known as Highway 100 So. and Vernon Ave. The buildings on the street at the time, which had included a law office, post office, and driving range, were demolished at about the time Lilac Way saw its demise.

Ground was broken for the Highway 100/36th Street interchange on July 9, 1984. The project had been delayed several times because of funding problems. C.S. McCrossan was the contractor. The City provided about $3 million of the project’s $9.5 million price tag. The project helped drive the final nail in the coffin of Lilac Way Shopping Center, as people stayed away from the construction zone.

The bridge eliminated one of the last stoplights on Highway 100. The pedestrian bridge was to be dismantled, divided, and erected at two other locations in St. Louis Park. One was over 36th St. west of Beltline Blvd., near the Rec Center. Another section was to be placed over railroad tracks to connect Dakota Park and Edgewood Ave., near Methodist Hospital.

2004

A $137 million Highway 100 project stretched from Glenwood Ave. to Brooklyn Blvd. through Golden Valley, Crystal, Robbinsdale, and Brooklyn Center. The project, started in 2000, turned a two-lane road with stoplights into a three-lane “free flowing highway” from 394 to 694. The construction season-ending MnDOT news conference was held in Graeser Park in Robbinsdale.

2006

The remaining two-lane section of Highway 100 between 36th Street and 394 was creating a huge bottleneck, but money to widen the highway wasn’t available until 2014. A stopgap solution was started in June 2006, whereby the State relined the road to make three lanes out of two. Extensive work was also done to turn the Highway 7 cloverleaf into a diamond.

2012

Although he didn’t make it to St. Louis Park, President Barack Obama traversed Highway 100 on his way to speak at the Honeywell Plant in Golden Valley on June 1, 2012.

The long-delayed expansion of Highway 100 at Minnetonka Blvd. and Highway 7 began in late 2014 and finished in 2016. The so-called “full build” project replaced the bridges over Highway 100 at Minnetonka Blvd. and Highway 7, as well as two railroad bridges. Pavement was replaced, and the new lanes are 12 ft. wide. The concrete median and a sewer line were replaced, and contaminated soil removed.

2016

The reconstruction of Highway 100, delayed for so many years, was declared complete at a ceremony on November 3, 2016. See video of the event Here!

Once the Pratts and the Hankes crossed the Aurora/Excelsior intersection on foot via Pleasant Avenue. 150 years later, from the western dead end of Wooddale, one can look across 14 lanes of pavement to see where the east side of Wooddale picks up. In typical fashion, you can’t get there from here. St. Louis Park was advertised as the place to be, “Out Where the Highways Meet” – but first you’d better have a car and know where the bridges are!