St. Louis Park’s borders are decidedly irregular and have seen several changes since the Village was incorporated in 1886. In the past, State law provided that cities or villages could annex property of adjoining townships without the permission of the local town boards if all the property owners request the merger. The following information is based on newspaper reports, city records, and our friend and former City Councilman Keith Meland. A sincere thanks to City engineer Mark Fremder for deciphering the descriptions of the Hopkins annexations and providing maps! We don’t have documentation for every annexation but we’ll keep looking.

ANNEXATIONS

FAILED ATTEMPTS AT GRABS BY MINNEAPOLIS

In 1879 there was a plan afoot by Minneapolis to annex all outlying suburbs into Minneapolis prior to the 1880 Federal census, in an attempt to boost the population figures for Minneapolis. It was all because of the intense rivalry between Minneapolis and St. Paul to be the biggest and best of the Twin Cities.

On February 22, 1893, a party of aldermen and officials from the City of Minneapolis visited St. Louis Park, led by A.M. Allen and Louis Gorham of T.B. Walker’s land Syndicate, the West Minneapolis Land and Investment Company. At the time the factories were booming, and the aldermen expressed a wish that they were within the boundaries of Minneapolis. In March, the joint committees on municipal corporations was considering a new charter, but was stuck on language – the way it was written, St. Louis Park, for example, could not be annexed to Minneapolis, since the territory to be annexed had to be unincorporated. The Panic of 1893 began in earnest in May 1893, presumably one reason why the talk of annexation ceased for a time.

In July 1910 the topic came up again when it was proposed that the villages in the immediate vicinity of the City be annexed into a “Greater Minneapolis.” This proposal came from the Minneapolis Real Estate Board, the Commercial Club, and the Publicity Club. It was felt that Minneapolis needed more room for factory sites. A typical opinion came from Ed. A Stevens, “prominent in the legal and political world of the city.” Said Stevens, “I believe that Minneapolis should get in on the ground floor this time and not let St. Paul or any other city take anything away from us that is our due.” Minneapolitans were still sore about the way St. Paul snapped up the Midway district, and wanted St. Louis Park and Hopkins to make up for the loss of territory.

The 1910 proposal apparently had some legs, for in January 1911 the Tribune reported that the citizens of St. Louis Park held a mass meeting in the Odd Fellows Hall to protest against the proposition to make them a part of Minneapolis. Several speakers denounced the plan, declaring that additional taxation would be imposed if the plan went through. In February 1911, the state legislature attempted to annex Hopkins, Edina, Robbinsdale, St. Louis Park, Golden Valley, and Columbia Heights into Minneapolis. Representatives of the Villages were hopping mad when none of the members of the Hennepin County legislative delegation showed up to meetings held to discuss the matter, and accused the legislature of “railroading” the bill through. Columbia Heights, incidentally, was eager to be annexed, but the action, of course, failed.

ANNEXATIONS OF LAND BY ST. LOUIS PARK

All of the land that St. Louis Park annexed in the 1940s and 1950s had originally been in Minnetonka Township. By the time Minnetonka incorporated as a Village in 1956, only 28 square miles remained of the Township’s original 36 square miles. Minnetonka became a city in 1969.

HOPKINS

There was a series of annexations in the southwest corner of the Park (Section 20, Township 117, Range 21). All of the annexed land came from Minnetonka Township. Three that we have documentation for:

Ordinance 288 annexed 10 acres with the following boundaries:

- East: Meadowbrook Road

- South: Excelsior Blvd.

- West: A line approximately lined up with Hopkins’ Homedale Ave. (east of Powell Road)

- North: The section line

It was basically a rectangle measuring 700 feet wide and 642.5 feet high. The ordinance was passed on December 22, 1947, and was effective January 1, 1948. This is now the site of Japs Olson Printing, at 7500 Excelsior Blvd.

Ordinance 345 was a similar annexation, with St. Louis Park taking land just east of the previous action. Boundaries were:

- East: The section line that is now Excelsior Way

- South: Excelsior Blvd.

- West: Meadowbrook Road

- North: The BNSF Railroad tracks/Oxford Street.

Properties included within this area are 7400, 7252, 7202 and 7192 Excelsior Blvd.; 3985, 3965, 3941 Meadowbrook Road; Excelsior Way; and 7305 Oxford Street, which is the City’s Municipal Service Center. Minnehaha Creek runs east-west through the property. The ordinance was adopted on November 21, 1940 and was effective upon publication in the Dispatch on November 25, 1949.

Ordinance 348 annexed a sliver of land in front of what would become Methodist Hospital. Boundaries were:

- East: Middle of Dakota Ave.

- South: Excelsior Blvd.

- West: Meadowbrook Blvd.

- North: A line that runs approximately between the present 3986 and 3990 Dakota.

The creek runs through this property as well. The ordinance was adopted on December 19, 1949 and took effect upon publication in the Dispatch on February 15, 1950.

Another annexation for which we don’t yet have documentation is the sliver of land in front of Meadowbrook Manor. Again, that would be between the section line and Excelsior Blvd.

KILMER

The Kilmer neighborhood was annexed from Minnetonka Township by Ordinance 451, enacted on May 17, 1954, effective June 27, 1954. It is located straight west of Highway 169 and south of Highway 394. It comprises approximately 80 acres, in Section 1, Township 117, Range 22. The northern 70 acres were owned by developers (Stanley) Ecklund and (Leonard) Swedlund and Magna M. Gabrielson. The southern portion was owned by Ecklund and Swedlund and Clara Marie Olson of the Lakeland Development Corp. Developers wanted it to be in St. Louis Park because of Park’s ability to provide sewer and water. Also, Park had only a 40 ft. minimum lot line and they could build more houses on the same land. The annexation took effect in August 1954.

SHELARD PARK

125 acres that would become Shelard Park were annexed from Minnetonka Township in 1955. It is the area north and west of today’s Highways 169 and 394. The annexation was requested by the owners of the property in order to build a $15 million development that would include a $5 million Oak Knoll Shopping Center. The owners had petitioned Minnetonka Township to rezone the property to allow development but were turned down.

Developer Wallace E. Freeman presented a petition, signed by all of the land owners, to the St. Louis Park Village Council in March 1955. Ordinance 473 was adopted on March 14, 1955 annexing land in Section 1, Township 117, Range 22. The land owners were:

- Wallace E. Freeman, 100 Mendelssohn Ave. (Highway 18, now 169).

- Harold and Fred Johnson, 9604 Wayzata Blvd. (Highway 12, now 394)

- Petersen-Russell Greenhouses, 9708 Wayzata Blvd.

- H.M. Cornish, 9808 Wayzata Blvd.

- John and Hazel DeMuth’s Merry Hill Kennels, 9920 Wayzata Blvd.

- Mr. and Mrs. Carl Dressel, 500 Mendelssohn

- Elmer T. Hess, 4701 Linnea Lane, Minnetonka

An article in the Minneapolis Star dated March 1, 1955 described the parcel:

The annexation area includes land both north and south of Wayzata boulevard west of highway 18. Most of the site lies west of Golden Valley directly across highway 18.

The site is roughly 2,640 feet wide on Wayzata boulevard going north to a depth of 1,860 feet.. The area south of Wayzata is approximately 1,000 feet along the boulevard, and about 500 feet deep.

Residents at a February 16, 1955 meeting at the Oak Knoll school voted 166 to 20 in favor of the project. Members of the Westwood Road Civic association filed a temporary restraining order to block the annexation – they were not opposed to the development but felt that their concerns about proper screening between new construction and adjacent homes were not being heard. After a court hearing the judge determined that St. Louis Park could go through with the annexation despite the threat of a restraining order. Protesting parties eventually dropped the request for an injunction in exchange for St. Louis Park adopting an ordinance requiring a buffer zone of a landscaped area and a height restriction of 2 1/2 stories on apartments. Westwood Road runs parallel to Shelard Parkway in Minnetonka.

Ordinance 473 was adopted on March 14, 1955, to be effective on July 1, 1955. With the annexation, all zoning was removed and owners had to apply to St. Louis Park for the desired zoning to meet their plans.

Robert Cerny was set to design the shopping center, which was to have 40 stores.

By August 1955 Freeman had dropped all plans for single-family homes on the site. He calculated that the shopping center would employ 300 workers, and the General Mills headquarters building at the northeast corner approximately 1,200. (General Mills was built in 1957, east of 169 in Golden Valley and is not part of the parcel.) The new proposal was for primary retail development, and light industrial was also on the table.

Freeman had originally proposed that Park annex 240 acres, which would have included a large residential development in Plymouth. The ultimate annexation did not include any property from Plymouth.

For whatever reasons, the Oak Knoll Shopping Center did not materialize. The Shelard Park subdivision was not platted until October 9, 1969 and was not built until the early 1970s.

TEMPLE’S GARDEN LOTS

In August 1955 developers Sam Segal and Victor Formo petitioned to have 30 acres south of Kilmer annexed to St. Louis Park from Minnetonka Township. The land would be used to build about 100 high-end homes. This petition was temporarily withdrawn.

Then in December 1955 the Segal/Formo petition was combined with a petition from a company called Morning-Park, Inc., owned by Maurice L. Grossman, P.A. McMillan, and Shirley Silver. Morning-Park had a contract for deed on the land from owners Daniel J and Mary C. Gallagher.

Minnetonka leaders were furious at this latest attempt at encroachment, and said that the homes should be built in Minnetonka using Minnetonka’s rules about lot sizes, setbacks, and sideyards. The Dispatch reported that “Town board supervisors will not go along with what they term ‘boxes in a row’ built in St. Louis Park. They feared the “herding” of children and a strain on the Hopkins school district, which would have to be responsible for the additional school facilities.

First reading of the ordinance that would annex the property took place at the June 4 meeting of the St. Louis Park City Council. Ordinance 530 was adopted on June 11, 1956 and was effective on publication on June 21, 1956. At that point St. Louis Park took on all governmental functions for the area.

In turn, Minnetonka Township supervisors held a meeting of Township citizens who voted to file a “quo warranto” (show cause) lawsuit to be heard at the Minnesota Supreme Court. The argument was that St. Louis Park did not have the right to take the land on petition of non-resident owners specifically for development of real estate. (Dispatch, June 28, 1956). Another argument was that the land did not abut St. Louis Park as required by state law.

Minnetonka also began the process of changing their governmental status from a township to a village, which would prevent any further annexations.

In July 1956 the Minnesota Supreme Court granted Minnetonka a writ of quo warranto, questioning St. Louis Park’s right to exercise sovereignty over the area. In August St. Louis Park answered the writ, denying that the action was illegal. The Court assigned the case to District Judge J.H. Sylvestre of Crookston. On January 14-15 , 1957, depositions were taken from the petitioners and it became clear to St. Louis Park City Attorney Edmund Montgomery and Minnetonka Village Attorney John Shanard that there were irregularities that were serious enough to void the annexation. Montgomery reported that “certain of the petitioners in this matter misrepresented their ownership.” It was found that some of the signers of the petition for annexation were not owners but friends and employees of developer Sam Segal. Shanard said that Segal had deeded his part of the property to five people who in turn deeded it to others to acquire supporters for the petition. Montgomery and Shanard presented a stipulation to Judge Sylvestre in which St. Louis Park was “declining all sovereignty over the area and declaring the attempted annexation null and void.” (Dispatch, January 20, 1957) Something called a Writ of Ouster was received and filed on March 11, 1957.

It was not quite over; in August 1958 a red banner headline in the Dispatch announced that the Grand Jury would investigate the “Tonka land grab,” with issues of taking money not reported to the IRS and phony signatures on petitions asking for the annexation. The whole affair ended inconclusively in September 1958.

Ironically, most of the property became Ford Park, which to this day belongs to Minnetonka, but is maintained by St. Louis Park.

BORDERS

NORTHERN BORDER

The northern border of St. Louis Park and Golden Valley has taken many twists and turns over the years. At first it was probably pretty straightforward, as Superior Blvd./Wayzata Blvd. most likely followed the section line between the two villages. However, Highway 12, and then Highway 394, did not follow a straight line, with the result that some property south of the highway ended up in Golden Valley and some property north of the highway belonged to St. Louis Park. Here’s how former council member Keith Meland explains it:

The original alignment of Wayzata Blvd., when it was called Superior Blvd., ran between McCarthy’s Cafe and the Boulevard Cafe. McCarthy’s was in SLP and the Boulevard was in GV. The old alignment was in a straight line and would pick up and run west from Winnetka Ave. about a block or so west of the Holiday Station in SLP and become GV running at the time to the north and west city limit of SLP. Eventually, when 394 was constructed, all the right of way in SLP was taken. The right of way in GV was later returned to GV as not needed. The car dealers are in GV and the residential area to the south is all SLP. I believe SLP acquired some land from GV to the north side of the Westwood Hills Nature Center so that it could not be encroached upon. This was done after the completion of 394 in that area c. 1984-85.

When 394 was proposed in 1967 or ’68, County Road 18 (now State 169) ended in GV at Mendelssohn Road. When it was built to 494, 394 was still in design. Ultimately more land was taken in SLP for the interchange right of way. The SE corner was taken because of topological problems on the SW corner and development in the NE and NW quadrants – General Mills and Shelard, primarily. My guess is that SLP lost 50 to 100 acres of undeveloped land to highway right of way. It helps to remember that only the NE quadrant was not SLP.

MORNINGSIDE BORDER

In 1945 the southeast boundary line between Morningside and St. Louis Park was changed. The old line ran north and south between Natchez and Monterey. Although Park was generally on a grid, the slant of Wooddale resulted in bisecting several lots and even some homes. This caused headaches for taxpayers and tax assessors. The Hennepin County Review of December 6, 1945 reported that the new line would run west along 43 1/2 Street, southeast between the lot lines at the rear of Oakdale and Wooddale. Homeowners whose lots faced Oakdale were now in Morningside, and lots facing Wooddale belonged to St. Louis Park. Both St. Louis Park and Morningside passed Ordinances that realigned the line as reported, except that the line actually runs west on Morningside Road. This accounts for the jagged edge at the southeast corner of the Park. Park’s Ordinance 227 was enacted on December 3, 1945 and became effective on January 1, 1946.

JAPS-OLSON LAND SWAP

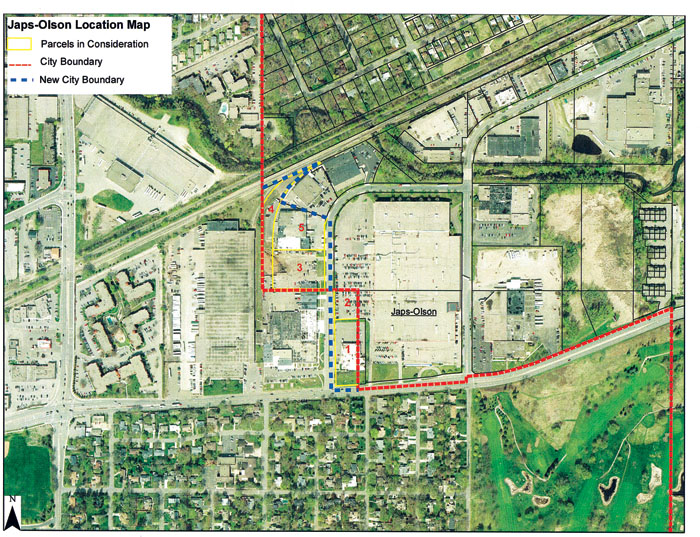

In 2015 the Japs-Olson Co., a direct-mail printing company located at 7500 Excelsior Blvd. in St. Louis Park, expressed a desire to expand its operation, and purchased land to build a 192,000 square ft. addition. The only catch was that while most of the land was located in St. Louis Park, part of it was also within the Hopkins city limits. Hopkins did not want to rezone the property, but was receptive to the idea of changing the city’s boundary so that the entire tract was in St. Louis Park.

On October 19, 2015, the City of St. Louis Park adopted Resolution No. 15-165: “Resolution for concurrent Detachment and Annexation of Land to and From the Cities of St. Louis Park and Hopkins.”

On October 20, 2015, the City of Hopkins adopted Resolution No. 2015-081.

The action was approved by the state of Minnesota Office of Administrative Hearings on November 6, 2015 (OAH 84-0331-32976). The swap provided Hopkins with more than five acres, ceding slightly more than two acres, with a net gain for Hopkins of more than three acres.

“GREATER MINNEAPOLIS”

Talk of Minneapolis annexing St. Louis Park into its city limits was seriously considered in the earliest years.

On February 22, 1893, several Minneapolis aldermen took a tour of St. Louis Park and its thriving factories, still buzzing with activity before the 1893 Financial Panic set in. On the special trolley car back to Minneapolis, “the aldermen spoke in high terms of the suburb and heartily wished it within the limits of [Minneapolis]. An agitation for is annexation was begun on the car while it was speeding them home.” (Tribune, February 23, 1893)

On March 21, 1893, the State Legislature was hammering out a new general charter relating to the organization of cities. “The first stumbling block was struck in the verbiage of section 18, relating to the annexation of adjoining territory … It was feared that St. Louis Park, for example, could not be annexed to Minneapolis under the section as it stands, as it provides that the territory to be annexed must be unincorporated. On the other hand, if this word is left out it would permit the people of St. Anthony Park, if they should so desire to quit St. Paul and go to Minneapolis.” (Tribune, March 22, 1893)

The topic was brought up again in 1910:

The annexation of the villages in the immediate vicinity of [Minneapolis] and creation of a “Greater Minneapolis” will, according to members of the Minneapolis Real Estate Board, the Commercial Club and the Publicity Club, fill a long-felt want in the Minneapolis industrial world. J.F. Conklin, president of the Real Estate board, and W.L. Harris, president of the Publicity Club, have given the idea their sanction, and following the formation of a public affairs department of all the booster commercial organizations of the city, the annexation of Hopkins and St. Louis Park will be discussed.

This action was contemplated because St. Paul had recently annexed the Midway, and the boosters of Minneapolis wanted to counter by adding territory as well. (Tribune, July 31, 1910)

But the folks in St. Louis Park were “Up in Arms” about the scheme to lose their autonomy. “Residents held a mass meeting last night in the Odd Fellows’ Hall to protest against the proposition to make that suburb a part of the corporate limits of Minneapolis proper. Several speakers denounced the plan, declaring that it would be unjust to impose additional taxation necessary should they be added to Minneapolis. (Tribune, January 26, 1911)

The State Legislature was in the process of drafting a bill that would add the villages of Hopkins, Edina, Robbinsdale, St. Louis Park, Golden Valley, and Columbia Heights to the city limits of Minneapolis. On February 6, 1911, the Tribune reported that about 50 residents came to meet with their county representatives, but none of the legislators showed, and in fact may have been hiding from the protesters. Columbia Heights was the only one of the named suburbs that actually wanted to be annexed by Minneapolis.