This chronology describes only a smattering of the actions taken by St. Louis Park to further the cause of preserving mother earth. Please contact us if you have any additional information or corrections.

Also see Garbage and Recycling in the Park.

For information on water pollution caused by Reilly Tar and Chemical, see the Creosote Plant.

Environmental awareness hit its peak around 1972, although much of it turned out to be short lived. Eventually, of course, the experimental measures taken in the ‘70s were fully executed later on.

ENVIRONMENTAL TIMELINE

At the turn of the century the Sugar Beet plant was having trouble disposing of the odorous refuse of the mill. They had been dumping it in the swamp and Minnehaha Creek and people living near the dumping sites were complaining of the stench and were threatening to bring injunctions to prevent the use of this method of disposal. The company did not feel that they could afford to install sewers to carry off the refuse because it would cost about $6,000. A disastrous fire in 1905 solved the problem.

The infamous Creosote Plant (Reilly Tar and Chemical) came to St. Louis Park in 1917. A full account of that struggle is located here.

In the 1926 re-codification of Village Ordinances, among the conditions prohibited were:

- water pollution by sewage, creamery, or industrial wastes

- noxious weeds and other rank growths of vegetation

- dense smoke

- noxious fumes, gas and soot or cinders

In June 1961 J.V. Gleason sued for an injunction against the City, which had rezoned his black top mixing plant at 2631 Virginia Ave. from industrial to residential-business after residents had objected to the smell of the blacktop. There were several homes in the immediately adjacent area that had been built in the 1950s. Below is a photo of Gleason and his eight 10,000-gallon storage tanks, as published in the Minneapolis Star (courtesy Minnesota Historical Society). A high-end home was built at the site in 1999.

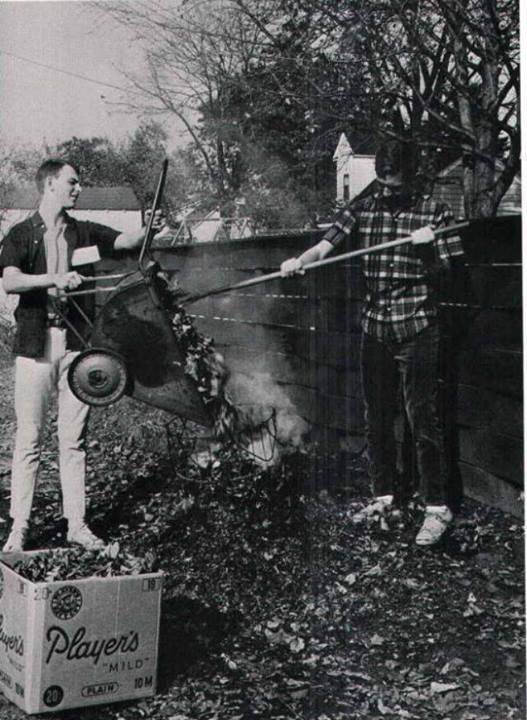

As early as November 24, 1966, the headline in the Dispatch read “Air Pollution is Local Threat, Officials Say.” Dr. Ellen Fifer, City Health Officer, predicted that if we don’t start to control air pollution now, “we could face a real health hazard within the next 20 years.” The pollution came from car exhaust fumes, trash burning, and industrial smog. She advocated State action, since pollution didn’t respect municipal boundaries. Here are some high school kids burning leaves for “Slave Day,” fall of 1965. At least they weren’t burning them in the street, which was often done.

The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency was formed in 1967 in order to control pollution of the air, water, and solids. Before its creation the only state agency that controlled pollution was the Water Pollution Control Commission.

In 1969 St. Louis Park became the only suburb with a strict anti-pollution ordinance. Based on ordinances in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Pittsburgh, and Albuquerque, its provisions were a basis for the State pollution control law. The St. Louis Park ordinance:

- banned the burning of leaves. Before that, people routinely burned the leaves they had raked every autumn, sometimes in the street.

- required polluters or possible polluters to be licensed

- required a license for burning refuse, including apartment house incinerators; no more back

yard burning barrels. - permits would be required for recreational fires and barbeques

- anyone burning oil as fuel must have a license

- asphalt plants, casting industries, foundries and smelters must be licensed

- operations giving off particulate matter, including trucks hauling sand.

- the ordinance included an odor clause, although the City wasn’t sure it would stand up in court.

The hope was to make pollutant activities too expensive to continue. The State law provided for financial incentives to reduce pollution. It also made it illegal to remove anti-pollution devices from cars. Opponents of the law included Reilly Tar and Chemical (Creosote plant), the National Coal Association, and the Minnesota Petroleum Council.

Park High students Mike Stutzer and Sue Gale started Have Everyone Limit Pollution (HELP) in February 1970. Their first focus was the creosote plant, which was under pressure to close by the city and the Federal Environmental Protection Agency (which began on December 3, 1970).

On April 8, 1970, the Echo reported on Students for Environmental Defense (SED), a high school level affiliate of the Pollution Report Center at the University of Minnesota. Although 15 Twin Cities high schools supported SED, Park High’s HELP organization (see above) chose to remain independent. SED’s focus was to work against no-deposit, no-return pop bottles. Other topics were Northern States Power and the Creosote Plant. HELP did plan to participate in SED’s High School Environmental Congress at the University on April 25. Each school had a booth with a topic – Park’s was how one-crop farming destroyed the fertility of the land.

EARTH DAY

Earth Day was founded by United States Senator Gaylord Nelson as an environmental teach-in first held on April 22, 1970. The St. Louis Park Sun noted it only as the traditional Arbor Day that year. The Echo reported that Earth Day at the U of M was marked by a rally, teach-in, and workshops. A High School Congress was held on April 25.

Woodsy Owl was created as the mascot for the first Earth Day. Wikipedia gives both ad exec. Harold Bell and and Forest Ranger Chuck Williams credit for coming up with the idea. But did they? Or did Steven Ritt, a third grader at Aquila School create it as the winning entry in a school contest? Ritt remembers clearly tracing his little hand to make Woodsy’s feet. We searched the paper for confirmation, but so far no luck. We’ll keep looking.

Park High’s HELP organized a variety of activities for 1970’s Earth Day:

- Information service center in the foyer

- Cleanup of the school grounds

- Action Day – urge students to pick up trash on the way to school

- Pollution films in social studies classes

- Teach-ins

- Media Day – exhibition of student films and photographs of pollution

- Talk by Bruce Watson, local meteorologist, to the entire student body on “Ecological Awakening”

On June 14, 1970, a new pollution law specifically defined pollution on the Ringlemann Scale, according to the Park High Echo.

In 1970 the City Council heard a proposal to switch from internal combustion engines to propane gas for city gas stations and city cars.

On May 5, 1972, a 13-hour telethon was held for clean water. Participants included Robert Vaughn, Roundhouse Rodney, Buster Crabbe, and Mr. Wizard (Don Herbert).

Bikes became more popular than ever in the mid ’70s, with people biking to work instead of driving. It was also the beginning of the bike trail movement.

Park High’s environmental organization in 1973-’75 was called Park Students for Environmental Protection.

In 1975 Minnesota’s Clean Indoor Air Act is the first in the US to limit smoking to designated areas.

The State legislature outlawed pop tops effective January 1977.

In 1980 the State legislature passed the Waste Management Act, which mandated that 16 percent of the waste stream be recycled by 1990.

In 1981 St. Louis Park was named a “Tree City U.S.A.” for the first time. The award is given to communities whose local governments have taken extra measures to protect and beautify public land through the use of trees. The award ceremony took place at the Capitol on April 27. The City has qualified as a Tree City ever since.

The Cedar Lake LRT Regional Trail is the trail that parallels Highway 7 through St. Louis Park. The portion of the trail that runs from Hopkins east to Beltline Blvd. was built in 1997. The trail section that runs from Beltline Blvd. east to where it connects with the Midtown Greenway was completed in 2001.

The North Cedar Lake Regional Trail was completed in 2000.

In 2013 the City Council voted to create an Environment and Sustainability Commission, also known as “Sustainable SLP.”