Much of the following information on El Patio and the Cotton Club is from Kent Hazen, and the book Joined at the Hip, A History of Jazz in the Twin Cities, by Jay Goetting (Minnesota Historical Society Press: 2011). Please contact us if you have any additions or corrections.

The building at 5916 Excelsior Blvd., now Bunny’s Bar and Grill, has a rich history. This page will tell the story of the various restaurants that have existed here. They are:

- The El Patio/Cotton Club

- Culbertson’s

- George Faust’s

- Anchor Inn

- Bongiorno’s

- Duggan’s

- Bunny’s

PREHISTORY

According to City tax records, the building was built in 1920. At that time, the adjacent Brookside neighborhood, not even 15 years old, was flourishing, and the older Center neighborhood was a few blocks down the street, although what is now Alabama Ave. may not yet have not gone through. The Dan Patch Railroad had come through in 1915.

On April 8, 1958, Cedric Adams wrote in his entertainment column that 20 years before, in 1938, the building started out as a farm house. The building was originally all frame construction. Adams wrote that some enterprising businessmen turned it into a lumber yard to increase profits. A few years later, “another man of vision” converted it into a cabaret, and the El Patio was born. This is not entirely accurate, as the building was up and running as the El Patio in the 1920s, as we’ll see below.

Four months later, in August 1958, Adams provided more details, although they don’t seem to match up chronologically either. He wrote that the place was turned into the Cotton Club in about 1940, when we know that it was the El Patio/Cotton Club as early as 1929. Adams did agree that “Ted Culbertson and a group purchased the El Patio, changed the name to Culbertson’s, and began one of the most successful suburban restaurant operations in the entire country.” (Minneapolis Star, August 8, 1958)

1929

EL PATIO – THE COTTON CLUB

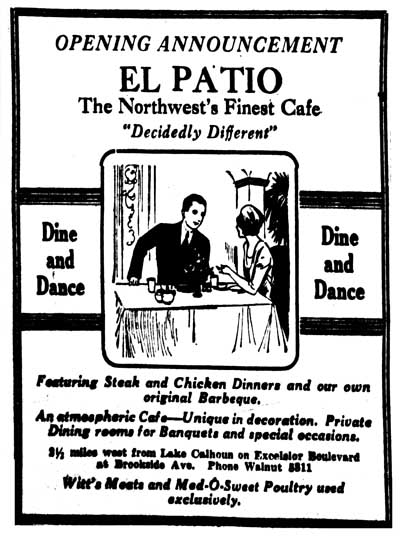

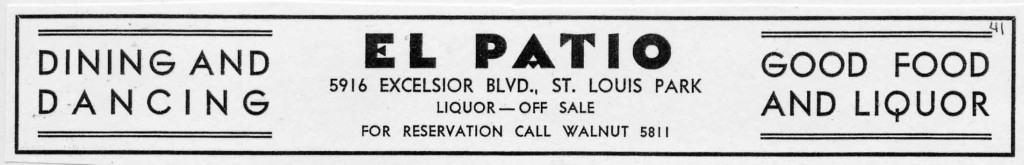

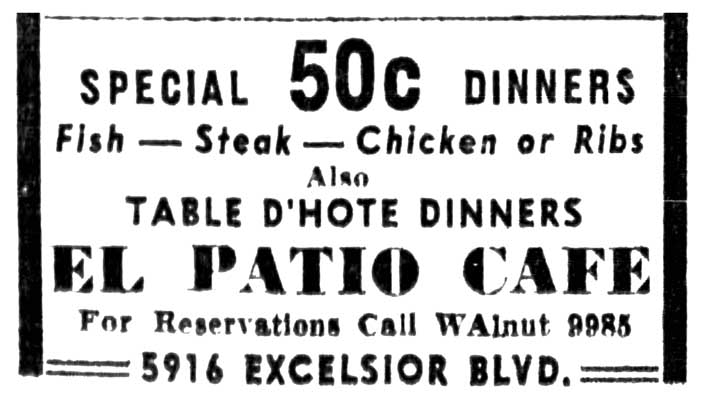

The El Patio, pronounced “el PAY sho,” was a cafe, dance hall, and after Prohibition ended in 1933, a tavern. One of the classiest establishments on the Boulevard, in the early days it catered to the Country Club and University crowds. Although there were plenty of cafes and speakeasies along Excelsior Blvd. closer to Minneapolis, the El Patio was ‘way out on the outskirts of town, before Highways 7 or 100 were built in the 1930s.

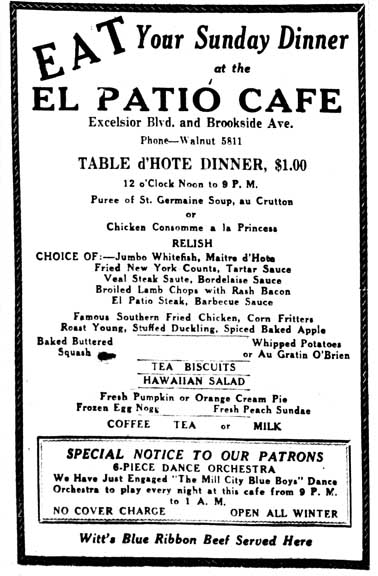

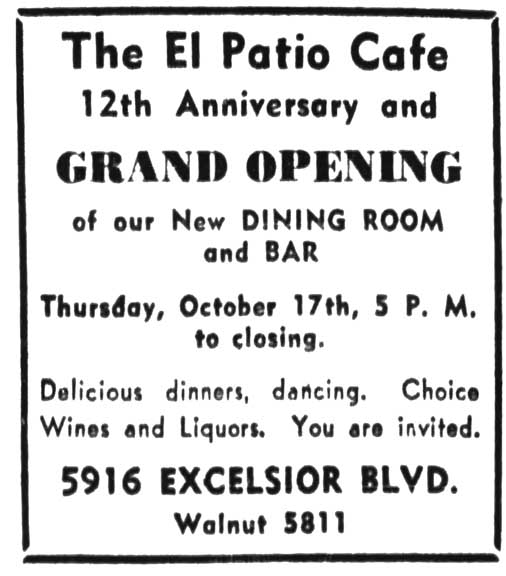

According to the ad below, it opened in May 1929, four years before Prohibition ended. However, the ad may be announcing its opening for the season; a 1940 ad announces its 12th anniversary, taking it back to 1928.

Owners

The owners were collectively known as “the Greeks.”

- In December 1932 Village Council minutes identify James Spain as the President of El Patio Cafe, Inc. This was no doubt a misspelling of James Spaise. Spaise was born in Greece in 1894/5, and lived in Minneapolis and worked as a waiter (1930) and proprietor (1940) of a restaurant, according to the Census. He was named as an owner of El Patio, along with George Broumas and John Eliopolos, in a 1939 newspaper account. In December 1945, O. James Spaise was listed as an owner of James’s Barbeque at 1414 Nicollet, identified as “former owner El Patio.”

- John Eliopolis (or Elipoulos) was born on May 22, 1897, in Greece. He came to the U.S. in 1917. In the 1920s he lived in Minneapolis and was listed in directories as a cook. In the 1930 Census, he and George Broumas (below) were listed as living on Excelsior Blvd. (no street address given), both single and working as cooks. He died in Greece in January 1979. See a picture of John under 1939 below.

- George Efstathion Broumas was born on January 5, 1890, and came to the U.S. in 1911. In the 1930 Census he was single, working as a cook in a cafe (with John, above). George died in Athens on October 18, 1972. His last U.S. address was 3973 Alabama, a house that was built in 1927, adjacent to El Patio. At the time of his death he had a wife, Sophia.

- John E. Ellis was born on July 24, 1899, in Greece. He came to the U.S. in 1911. In the 1930 Census he was listed as a waiter at a road side inn. In 1940 he was a partner/proprietor of a cafe. Both years he was single, living with his brother George in Crystal. After he sold El Patio he went on to run Ellis’s Log Cabin Restaurant in Crystal. Ellis was a prominent member of the community, belonging to the AHEPA Lodge, Compass Lodge AF & AM, Zuhrah Temple, and Robbinsdale Lions Club. He died on January 13, 1976, in Golden Valley. He was survived by his wife Canella (Feb. 6, 1921 – Oct. 26, 2000) and daughter Stavroula Joanne.

- George Ellis was born on June 16, 1891, in Greece and came to the US in 1907 or 1914. In the 1930 Census he was a cook at a roadside inn, and in 1940 he was a partner/proprietor of a cafe. George lived in Crystal with his wife Sophia, three sons, and brother John.

- George A. Katsmedas was identified as a former owner of the El Patio in his obituary when he died on July 20, 1951, at age 70. He had lived in Minneapolis for 30 years and had a few restaurants since 1927.

According to a former waitress at El Patio, “The Greeks” were strict on liquor, although one Sunday night a big band came in and a lot of “cold coffee” was served. When 3.2 beer (“select?”) became legal in 1933, customers would buy a bottle and supply their own harder stuff. During the Depression, El Patio provided meals to the needy.

On the Radio

From very early on, music was part of the dining experience at the El Patio. On September 11, 1929, an ad was placed for a five-piece orchestra for the El Patio Cafe, Brookside, Minn. [In those early days, for some reason, Brookside was often identified as if it was its own village, although it never was. St. Louis Park was a collection of disparate neighborhoods, and Brookside was just one of them.]

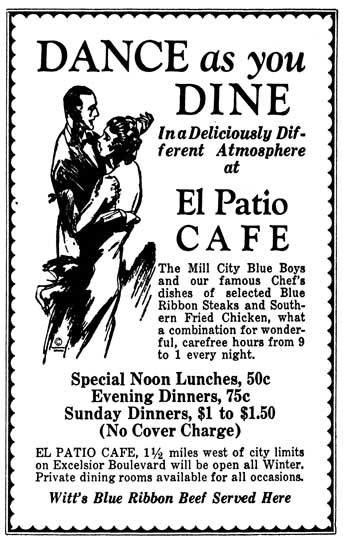

Orchestras played for dancing and their music was broadcast over the radio over telephone wires. The first station was WHRM, a long defunct radio station, with broadcasts starting in October 1929. Broadcasts moved to WDGY in December 1929, with music by Polta’s El Patio Orchestra and the El Patio Play Boys.

The ad below may be hard to read, but it reflects an ambitious menu, and announces that the Mill City Blue Boys were on hand for musical entertainment.

1934

The Cotton Club

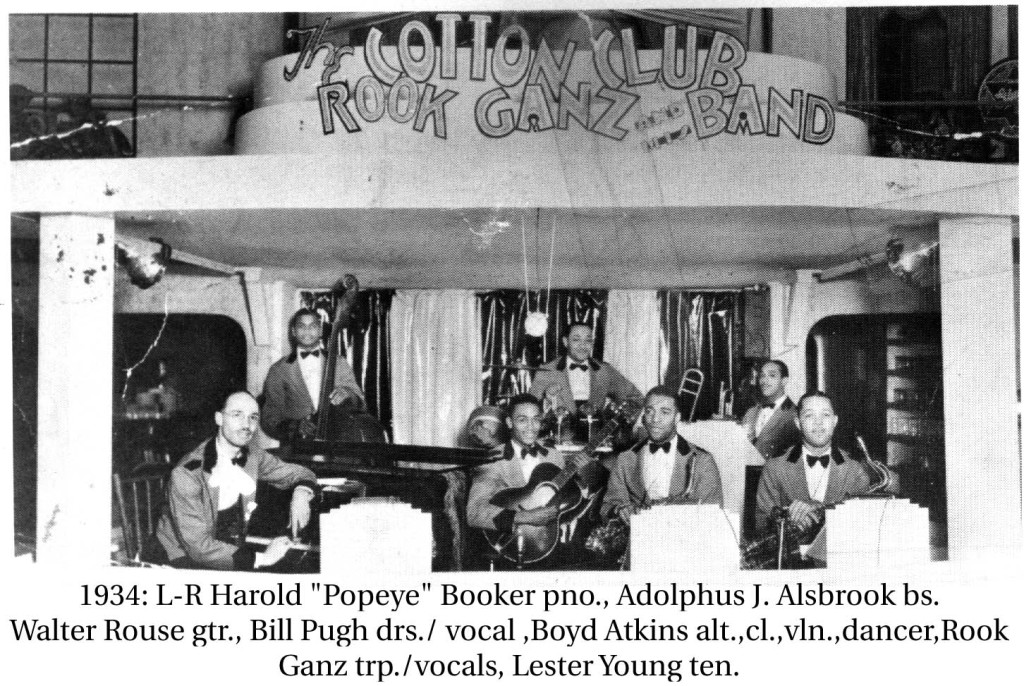

For several years, El Patio was concurrently known as the Cotton Club, named after the famous nightclub in Harlem (1923-1940). (There had been another Cotton Club in Minneapolis at 6th Ave. N. and Lyndale.) When the Apex Club in Minneapolis was shut down in 1934, club manager Pete Karalis signed the musicians and looked for a place for them to play. The Census lists a Peter G. Karalis who was born in Greece in 1888 and came to the U.S. in 1903 with his brother Christ.

Karalis said, “I sold the idea to the four Greek boys at [El Patio]. [One source said Karalis was a relative to one or more of the Greeks.] I then auditioned the group with Bob DeHaven and Lee Whiting at WTCN. They really liked the group and said they’d give me a line out there for thirty-nine dollars a month. I spent the remainder of my capital on paint to write ‘Cotton Club’ on the roof. We had a fairly good dinner trade, and the boys were proud of their restaurant… The group used to play the dinner shift.” (Joined at the Hip, page 83)

There was a reference to the “Cotton Club (El Patio)” in the 1934 Echowan St. Louis High School yearbook. An article about a fight in June 1934 referred to the place as “a tavern known as ‘the Old Cotton Club’ on Excelsior Blvd.” Other physical evidence of it is in the 1937 village directory, which listed the establishment as El Patio-Cotton Club. Otherwise it was referred to only as the El Patio in Village Council Minutes and village directories.

PHOTO OF THE EL PATIO

The only known photo of the El Patio is the one below. One can clearly see the “El Patio” vertical sign over the shoulder of the man on the right. If you look long and hard enough, you can see that the roof says “Dine [and] Dance” and, underneath, “Cotton Club.” A closeup of the photo reveals that the license plate on the car they are leaning on has the year 1941 on it. Thanks to Rick Sewall for finding this in our own collection!

Although these men might look a bit menacing, they are just St. Louis Park school friends, all born in 1916 and 1917, and all in their early 20s in this photo. They all registered for the draft on October 16, 1940. They are:

Bill Finnegan, who lived at 4708 W. 43rd Street. In 1940 he worked as a truck driver for Suburban Drayage, which might mean that he was a garbage man. He served in the Navy from 1942 to 1946, died in 2008, and is buried at Fort Snelling.

Bob Felber lived at 5924 Oxford Street, and worked at the lumber yard across the street from El Patio. He served in the Army Air Corps in World War II from 1942 to 1945, died in 1993, and is buried in Sioux Falls.

Richard Dahlquist lived at 6230 Cambridge, and in 1940 he was a student at the U of M. It appears that either because of his student status, or because of his height (6′ 4″), he did not serve in the War. He died in 1991 in Indiana.

Henry Swoboda lived at 6015 W. 37th Street, and in 1940 he delivered groceries for Swenson’s Market on Walker Street. At the time he registered for the military in 1941 he worked at Pockrandt Lumber on Highway 7. He served in the Army from 1942 to 1946.

Kent Hazen: “Karalis brought in Boyd Atkins from Chicago to lead the band of local musicians he then presented at the Cotton Club. Among the local players were trumpeter Rook Ganz and tenor saxophonist Harry Pettiford. Atkins was a composer/arranger of some stature who also played reeds and piano. In 1935 Karalis brought in Lester Young to replace Pettiford. Young was with the Atkins band at the Cotton Club in 1936 when he received a telegram from Count Basie asking him to join his band back in Kansas City. Lester made his seminal recordings with Basie that same year.”

“One of the earliest assemblages of world-class talent on a Twin Cities stage was the Cotton Club or El Patio in St. Louis Park. Joined at the Hip, page 39.

Again from Joined at the Hip: “The place was clean, neat, well run, and without rough stuff. It was the more established and familiar Minneapolis musician Rook Ganz whom people came to hear. George Putnam, later with Pathe News, was the radio announcer … Lester would leave the bandstand for some of his solos in order to stroll and serenade the diners at their tables and booths.” (page 84)

Drummer Bob Burns described how jam sessions at El Patio often turned into all-night affairs: “We started work at nine o’clock with a six-piece orchestra; at one o’clock, we cut down to three; by one-thirty, we’d have fifteen to twenty men on the stand, everybody blowin’. This was not only local musicians, but, remember, it was the era of the big band: Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, Glenn Miller – men like that on the stand at the same time. We’d work there until three o’clock in the morning, shut down, then go up north where Rook and the other fellas were playing. We’d stay there ’til eight, nine o’clock in the morning. If some of that music could have been recorded, I’m sure it would go down in the archives of history as some of the greatest ever performed.” (Joined at the Hip, page 92)

Hazen: “Atkins led the Cotton Club band until 1940, when he moved on to lead a band at a club in Peoria, Illinois. In the 1950s & ’60s Atkins was deeply involved in the Chicago blues and R&B scene, including collaborations with Elmore James, Magic Sam and Muddy Waters.”

Don Lang of Downbeat Magazine wrote in the 1940s that “The Cotton Club was the last Minneapolis spot to employ a colored band.” (Joined at the Hip, page 86)

1939

Trouble at El Patio

As can be expected, having a roadhouse with black musicians playing hot jazz late into the night in a suburbanizing village was drawing more and more ire from its neighbors.

On March 8, 1939, the El Patio was fined $25 for staying open after hours. On March 11, bartender-partner James Spaise was fined another $50 for “permitting minors to be in a place where intoxicating liquor is sold.” This was the result of an incident on February 25, 1939, when three youths lied to Spaise about being 21 and were served drinks. The other two partners, George Broumas and John Eliopolos, were not fined because they worked in the kitchen and did not have contact with patrons.

The two charges were filed after reports that an earlier complaint had been quashed by the arresting officer because of pressure from his superiors. (Minneapolis Star, March 9, 1939; Minneapolis Tribune, March 12, 1939)

This controversy led to another, and a few days later, the Minneapolis papers seemed to be making fun of St. Louis Park’s problem. One article began,

“Jitter bugs” prancing to strains of “hot music were blamed for revocation of the tavern and 3.2 beer licenses of the El Patio Cafe on Excelsior boulevard by the St. Louis Park city council.

The citizen who brought the problem to the council’s attention at their meeting on March 13, 1939, was one Norman Hague, who vehemently opposed allowing the joint to jump after closing time. After his impassioned speech, the council voted to revoke the cafe’s 3.2 beer license (but not the hard liquor license). They also revoked its tavern license, which meant that there could be no dancing. The councilmen even passed a motion commending the policemen who gathered evidence against the cafe. (Minneapolis Star, March 14, 1939)

The St. Louis Park Spectator reported that Mell W. Hobart represented a committee from Brookside that insisted that something be done. The indignant crowd, and even the Mayor himself, mentioned rumors about the place; one citizen was quoted thusly: “It is a known fact that they have been catering to high school kids for years, serving near beer to be spiked.” Mayor Nelson voted that the club keep its licenses, but was the only one.

Revoking the cafe’s hard liquor license required a public hearing, however, and that was held on March 20, 1939. A packed house of 65 people came to voice their opinions, and most of them were the complete opposite of those expressed at the council meeting the week before. Jack McCarthy asserted that the cafe had a “good, clean operating record for the past 10 years, and complaints against it were few and far between.”

Peter E. Kamuchey, attorney for the cafe, went as far as to say that “The El Patio is run almost as well as a minister operates a church.” “These boys have run the place 10 years without a single conviction until this last trouble.” Fred Peters opined that closing the cafe was too stiff a penalty for the violation, and would throw a score of people out of work and cost the village taxes.

“This is the best joke the Minneapolis newspapers have ever had,” shouted Jack Drummond when a photographer’s bulb flashed. “Let’s get it settled!” After the Villagers revealed an “overwhelming sentiment in favor of permitting the cafe to continue operation,” the council voted not to revoke the tavern’s hard liquor license, with the exception of Torval Jorvig, who voted against all liquor establishments.

At the next village council meeting on March 27, 1939, the council renewed the cafe’s tavern and 3.2 beer licenses it had revoked earlier. The Minneapolis Star, still making fun, wrote that “More interest was expressed last night in selection of a village dog catcher.”

1940

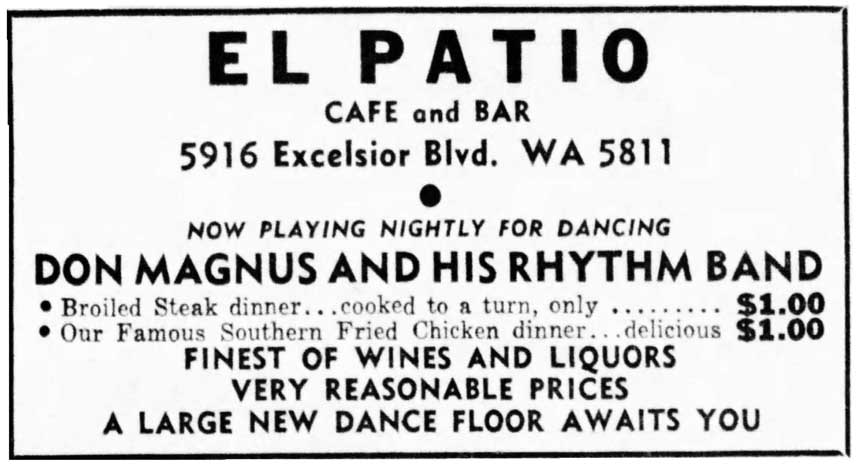

The ad below indicates that the El Patio was shut down for remodeling in 1940. Those changes were made in masonry. It also indicates that the place opened in October 1928?

1945

An odd item about the El Patio appeared in the Minneapolis Star on October 11, 1945, with the headline “Gypsy ‘Gyp’ Band on Job, City Warned.” The article warned of two families of Gypsies who were victimizing businessmen from Massachusetts to Minnesota. Seems they had poured asbestos cement into three ovens at the cafe “to insulate them,” charging $200 for their service. The Better Business Bureau heard about it, and repairmen from the Minneapolis Gas-Light Co. had to remove it before there was a serious explosion. On top of that, legitimate repair work should have only cost $25 an oven, gas company officials estimated.

1946

El Patio Closes

On August 8, 1946, the Tribune published an ad by the El Patio, selling 20 complete leatherette booths and tables in “A-1 condition.”

The ad below indicates that El Patio would close its dining room on Monday, August 26, 1946, for remodeling with the intention of reopening at some time that same year under “new ownership and policy.” The bar would stay open during renovations. A neighbor remembers that it was closed for quite awhile before opening again as Culbertson’s.

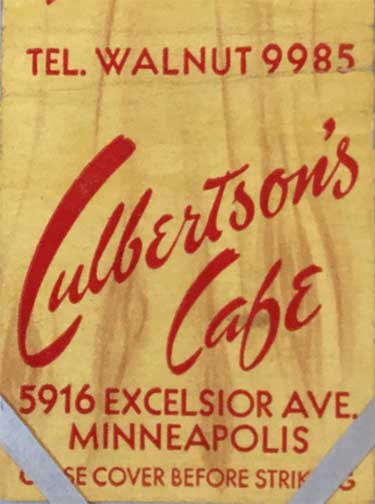

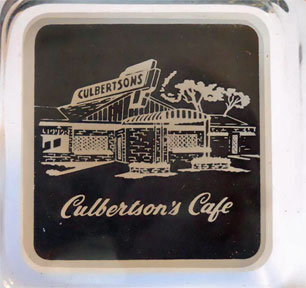

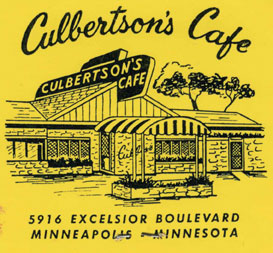

CULBERTSON’S

According to a sports article in the Minneapolis Star, Ted J. Culbertson opened Culbertson’s Cafe on August 19, 1946. That does not compute with the ad above that says that El Patio would close on August 26. But it did exist in September 1946. Go figure.

This restaurant, an upscale steakhouse, was said to be patronized mostly by people outside of St. Louis Park. Journalists were known to hang out there. In the early 1940s, Ted Culbertson had been a co-owner with Keith McCarthy of McCarthy’s Cafe.

1947 – 1948

In 1947 the building was in pretty bad condition when the Building Inspector wrote a letter to the Village Council citing numerous violations. Things were apparently cleared up, and on August 24, 1947, an ad was placed announcing that Culbertson’s was now fully air conditioned.

A 24’ by 60’ room was added on the west side in August 1948, according to city building permits.

1949

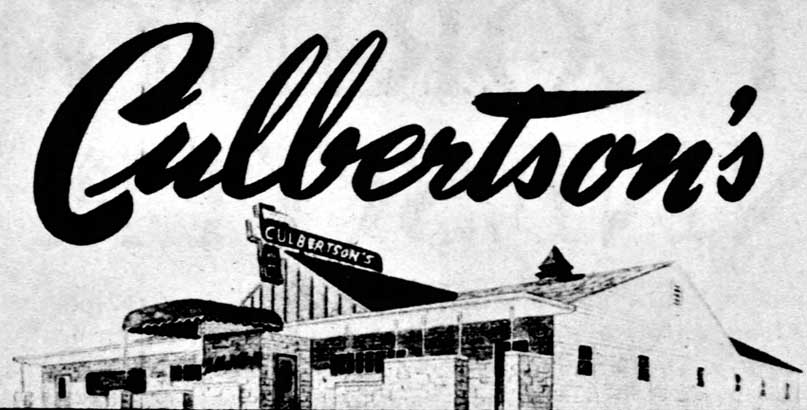

The photo below is dark but shows the building’s lines and front entrance on Excelsior Blvd. in 1949.

1955

The photo below from 1955 shows many interesting things: the proximity of the club to the railroad tracks, suggesting that patrons might have taken the train to this outpost way back in the 1920s. Also, the original portion of the building was the middle, and the rooflines of the additions faced the opposite way. Another item of interest is that the front door faced Excelsior Blvd., in an era when on-street parking was plentiful.

1958

There was a significant fire at Culbertson’s in January 1958 (“the other night,” said Cedric Adams in his January 23 column). Adams credited hostess Ruby Berg for keeping a cool head while herding the customers out, and organist Rollie Altmeyer for playing “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” “until he felt fire singeing his breeches” and then “There’ll be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight.” (Minneapolis Star)

In response to the fire, Ted Culbertson and his partner Elden Rothgeb decided to do the entire cafe over from vestibule to kitchen, reported Adams on the following June 13. Work consisted of:

- An enlarged, all-formica kitchen, “only one of its kind in the world,” which will turn out 200 steaks at once from its gas broilers.

- A renovated dining room with new tables and chairs, and new booths that will seat 150. This was later amended to 500, with four private dining rooms that could be divided into seating arrangements from 12 to 150.

- Carpeting and a “multi-vaulted ceiling” to deaden the noise to a murmur. Adams alternately described the ceiling as “lowered and acousticised.”

One of the many charming features of the place was a “pass-through” from the ladies room to a service bar, so that ladies could get drinks without their husbands knowing about it.

Boe Construction Inc. built the addition, which Adams reported to have cost $250,000. He also said that it was done without the loss of a single day’s business. And in the end, there was only one main wall left of the old Culbertson’s and the old El Patio. Adams had his facts wrong about timing, though, so let your eyes be your guide on that one.

On August 11, 1958, Adams reported

that the dining room ceiling had been lowered and “acousticised” and the floors in every room had been carpeted, to cut out the noise problem that had plagued the place since the El Patio. The new restaurant had a seating capacity of 500, with four private dining rooms that could be divided into seating arrangements for from 12 to 150. The big private dining room would be used primarily for conventions. Ruby Berg, the meeter and greeter, Dora Sahl, and Russ Mass had all been with Culbertson’s since it opened. In 1958 the club had a staff of 89.

The renovated restaurant would feature Rollie Altmeter on the organ for dinner, and head a three-piece orchestra comination for dancing in the new dining room for dancing in the new dining froom. Ozzie Dial, “the darling of the Steinway,” will be singing her torchies in the lounge.

1960

Harry Pence and the Dan Patch

An oft’ told story may have started with Cedric Adams, in his entertainment column in the Minneapolis Star dated March 11, 1960. It may be true, it may not. It may have happened in 1960, it may have happened in 1920. We do know that Harry Pence took over the Dan Patch Railroad in 1916 when Marion Savage died. But Harry Pence died in 1933. But there was another Harry Pence who was a pal of Ted Culbertson in the 1950s, perhaps Harry, Jr. Here is the entire article.

A St. Louis Park policeman burst into Culbertson’s cafe the other night shouting, “Anybody in here who parked a new Cadillac on the railroad tracks just outside the door?” A voice from inside answered clearly, “Yes, I did.” The cop approached the owner of the voice, Harry Pence. “Don’t you think you ought to take that car off the tracks?” “I don’t know why I should,” Pence responded. “I’m president of the railroad.” “But supposing a train came by?” the cop questioned. To which Pence replied, “Look, don’t you suppose as president of the railroad I know when our trains are running?” The car stayed there.

1963

A further addition was built by Culbertson in 1963, according to City building permit records.

Joined at the Hip mentions that a series of live jazz broadcasts was produced by Dick Driscoll for KQRS in the 1960s (page 185). The June 1963 Twin Citian promised Entertainment nightly.

1964

Culbertson’s on-sale and off-sale liquor licenses were transferred to the Halseth Corporation on September 17, 1964. Stockholders in the Halseth Corp. were Perry Halseth, his son L. Richard Halseth, and Ted J. Culbertson. The Halseth Corp. bought the stock of Culbertson’s and operated the cafe and liquor store. Halseth was the majority stockholder and his son and Culbertson were minority stockholders.

1965

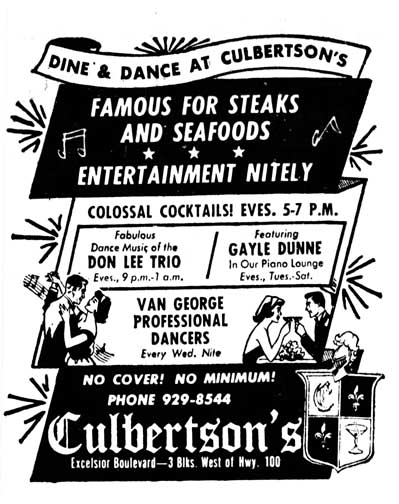

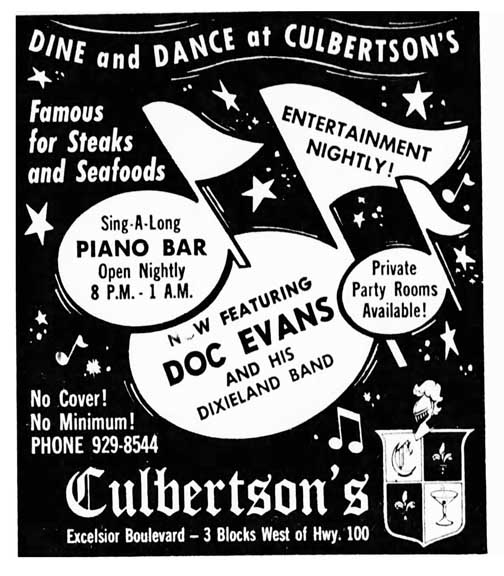

Culbertson’s was apparently a hip place to hang out in 1965. A newspaper ad from 1965 features the “Fabulous Dance Music of the Don Lee Trio,” Gayle Dunn in the Elbow Room Piano Lounge, and the Van George Professional Dancers every Wednesday night. 1965 was the year of Go-Go, so one could assume that the Van George Professional Dancers might have been in cages or worn white boots?

In 1965 the Culbertson’s cocktail hour featured lingerie shows, as pictured in a huge photo of ogling men in the October 17 Minneapolis Tribune Picture Magazine. The photo is too dark to post, but the caption reads:

The gowns grow shorter as the cocktail hour lingerie show progresses at Culbertson’s Cafe. The Model reminds viewers that they may buy anything that catches their eye, “in the way of lingerie, that is.” Three girls do the show, taking turns as the narrator with such comments as “You’d better order another martini, ’cause we’ll be right back with some swingin’ bikinis.” One of the girls makes more money modeling 5 hours a week than she does in her 40-hour receptionist job.

1968

In 1968 there was one band in the Continental Room, one in the Back Room, and also a Piano Lounge.

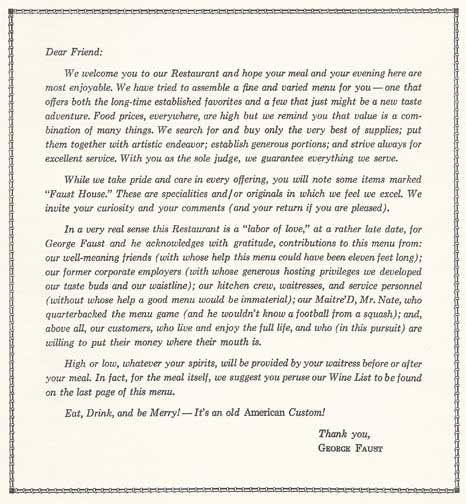

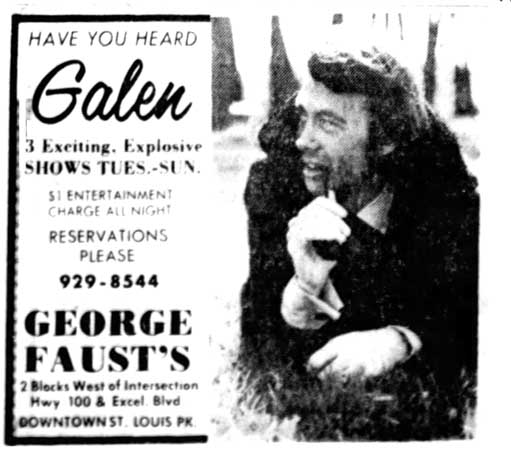

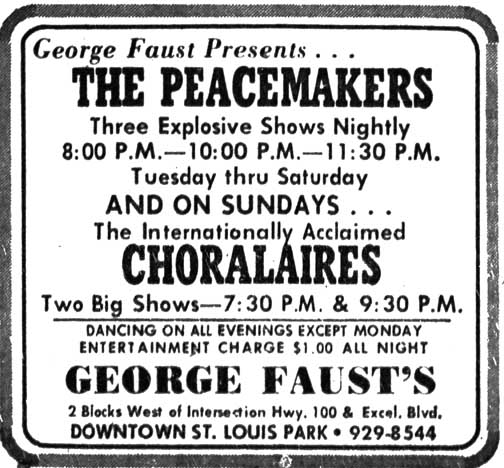

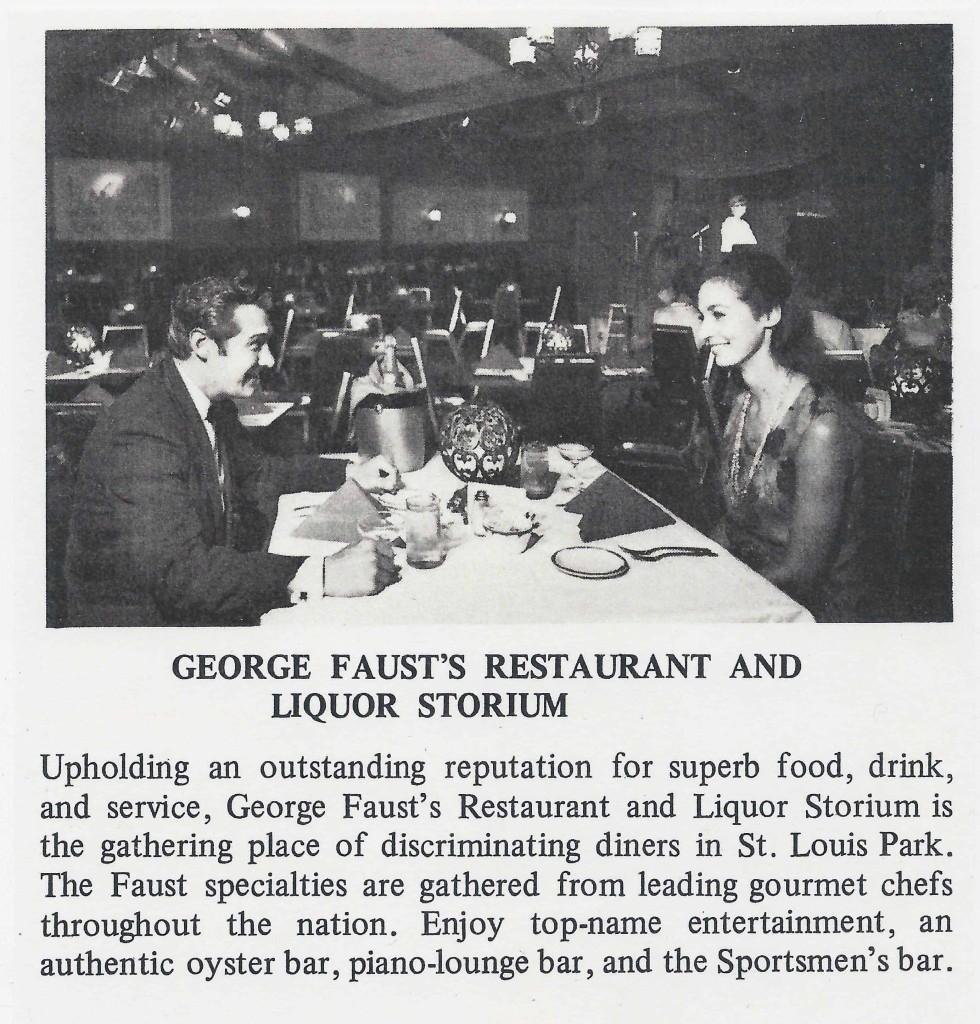

GEORGE FAUST’S

George Faust, a former U of M football hero, was the next to run the establishment, heading up George Faust’s Restaurant and Liquor Storium from October [December] 1968 to 1971. The liquor license was transferred from Perry Halseth. One unique draw was their raw oyster bar. A comparison of singles bars from July 1971 describes Faust’s as catering to an older “thirtyish” crowd.

Faust got in trouble a couple of times for serving 20-year-olds with fake IDs. In March 1970 the City Council ordered the place closed for 10 days, on the erroneous report that he had served a 15-year-old. The shutdown was later rescinded as being too severe, when Faust said that the shutdown would cost $10,000 and force him out of business.

During its entire run, George Faust’s identified itself as “Formerly Culbertson’s.”

One explanation of Faust’s demise is that George’s glory days were back in the ’30s, and his businessman clientele grew weary of his football stories. On September 29, 1971, it was announced in the Minneapolis Star that George Faust had sold the restaurant to Lyle Ebeling and Louis Gydesen of Minneapolis, and they would take over on Friday, October 1, 1971. Faust said he would be joining the staff of a Minneapolis firm in a managerial capacity. One source said that he went back to his previous profession selling frozen meat.

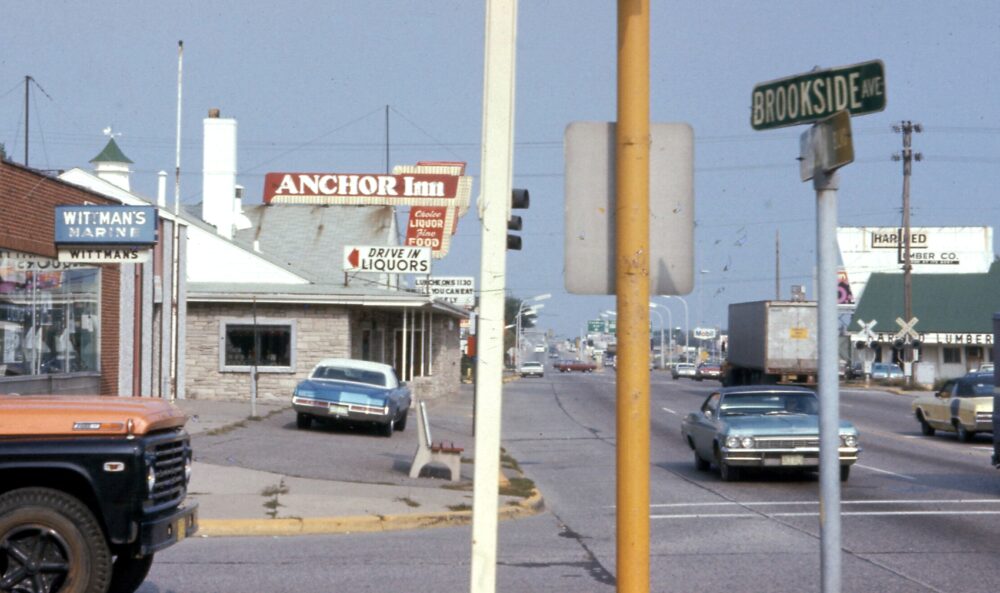

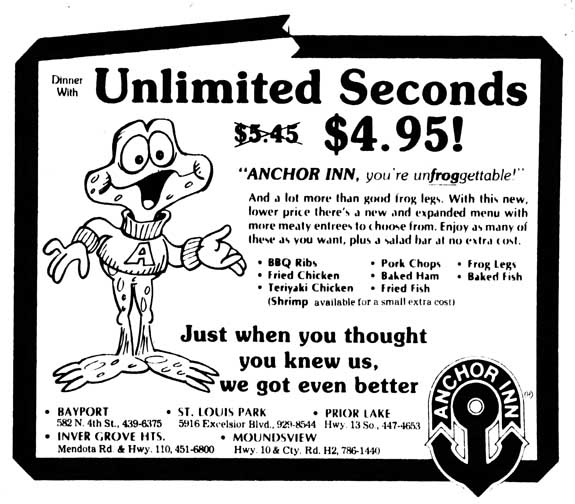

ANCHOR INN

The first ad for the Anchor Inn appeared on November 27, 1971. The Anchor Inn was a chain, and this was the second one owned by Louis Gydesen, who owned the one in Bayport.

The restaurant featured all all-you-can-eat format, which spelled disaster for some waitresses who had worked for Culbertson and Faust, as they received smaller tips. The restaurant had a long run, lasting until 1981.

The St. Louis Park Dispatch reported that on June 17, 1972, there was a fire that was deemed suspicious. No outcome was reported, and it did not make the Minneapolis papers.

Al Hartman remembers his time working at the Anchor Inn:

In 1975 I got a job bartending at the Anchor Inn. To learn how to bartend and get the job I put in 20 hours for free in their kitchen service bar. The tag line of the restaurant was “The Home of Waitress Served All You Can Eat.” The waitresses still got decent tips, I think, (maybe not as good as working for the previous restaurants at that location but I am not sure if many had been there that long), at least I did as a bartender, but I was union also and got a good wage too. The plan for the servers was to load customers up on bread and coleslaw first. They came out with an aluminum foil covered tray with the food on it and each time someone ordered any of the all-you-can-eat food again, the portions diminished on that tray incrementally.

The menu was mostly beer battered and deep fried with chicken and shrimp being quite popular but I remember they also had unbattered ham slices. The cooks would pop up at the service bar occasionally for a pitcher of beer to make the beer batter. At one time I remember a customer complaining about the beer in the batter as he was an alcoholic and should not have the beer in anything. We all wondered why he was there then as the beer batter part of the whole thing was pretty well promoted.

There were two bars at the time: the Piano Bar on the Northeast end and the Sportsman’s Bar on the Southeast end. The piano bar had great piano players with quite a selection of songs. I enjoyed asking them to play “Hernando’s Hideaway” as it was obscure, they actually had the sheet music, and customers seemed to like to sing along to that along with my other fave “Yes, We Have No Bananas.”

The Sportsman’s Bar was better lighted. It was more no nonsense bar and had a TV to watch sports on. Bill, the day bartender, I think actually retired from there with a bartender union pension. Both of the bars had black plastic booze metering dispenser tops on their bottles to make sure just a shot was poured. Dick Chapin and Lyle’s step son Terry were both evening managers under Lyle at the time.

The Anchor Inn closed in the fall of 1981.

BONGIORNO

David Bongiorno came to Minnesota from Erie, Pennsylvania in 1959. In about 1961 he became a co-owner of Mama Rosa’s Italian Restaurant in Minneapolis, which began as a pizza parlor in 1954. Bonjourno may have been an excellent chef, but his businesses suffered from three major disasters.

In 1971, Mama Rosa’s was hit with a strike for better pay, safer working conditions, faulty and defective equipment, a larger work force, an end to alleged discrimination in hiring, unjust firings, and longer skirts for waitresses. The two-day strike ended with pay raises and an agreement that waitresses could choose the length of their own skirts. (Minneapolis Tribune, September 2-4, 1971)

Breakfast at Mama’s opened in 1974, and was hit with lawsuits in August 1977 when 130 people got food poisoning after eating eggs Benedict. Then, both restaurants were closed on October 27, 1978, because of an outbreak of hepatitis and four people were briefly hospitalized. At the time of the hepatitis scare, Bongiorno had another Mama Rosa’s in St. Paul, and had been thinking of opening another restaurant in St. Louis Park, but business was so bad and he and his family were taking so much abuse that he was afraid for his future. (Minneapolis Star, December 8, 1978)

He sold Mama Rosa’s and opened the Bongiorno Ristorante in St. Louis Park in 1981. He advertised “Italian Food Prepared the Northern and Southern Way.” Will Jones reported that Bongiorno “got tired of all those grapevines on the West Bank and I’ve always liked the glamour of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers movies, so I just had to go this way.” Jones described the decor as “a pink-accented jewel box of a main dining room that looks like a supper club set right out of ‘Flying Down to Rio’ or ‘The Gay Divorcee.'” Unfortunately, non-smoking patrons were shunted off to a second-hand space where the only way to catch a glimpse of the action was to stretch one’s neck and peer through archways. (Minneapolis Tribune, June 19, 1982)

A review dated July 1982 deemed the food magnificent. Bongiorno’s also brought music back to the building; from August through October, 1982, the classic Percy Hughes trio was engaged to entertain.

Unfortunately, Bongiorno spent too much time and money fixing the place up and the establishment was gone sometime after March 1983. Bongiorno passed away on October 27, 2012.

DUGGAN’S

In November 1983, William F. Duggan purchased the building from Northwest National Bank for $608,000. Bill Duggan was born on December 31, 1923, and grew up on a farm at 62nd and Highway 100 in Edina, which his parents sold and became a large subdivision in 1953. Duggan went to Park High in 1940, since Edina didn’t have a high school at the time, and was a friend of Jim Jennings. Ads for Duggan’s American Bar and Steakhouse began to appear in December 1983.

A restaurant review by the Tribune’s Karin Winegar reveals that Duggan was the silent backer whose partners were restaurateurs Robert Engel (his son-in-law) and David Ariz of Seattle. They had been scouting the demographics of the Twin Cities, looking for populations of well-heeled 25 to 50-year olds.

Trendy touches of the time were mesquite, neon, natural woodwork, ceiling fans, interesting wine, neo-healthy entrees, Italian salads, gelati, wine labels on the walls, framed photos of food, wicker, dried weeds in baskets, cane-backed chairs, earthtone wallpaper, Celestial Seasonings herbal teas, unsalted butter, and sparkling apple cider, reported Winegar. (April 22, 1984)

Willie’s Bar was declared open in December 1984. A photo of Mr. Shakespeare accompanied the announcement. A subsequent ad featured William Holden. A review by food critic Jeremy Iggers in 1988 reported that the restaurant was quite popular and the parking lot was full.

An ad/article from April 15, 1994, reveals that Bob Engel was the front man, while David Ariz was the chef. They moved here in 1982 from West Coast and Hawaiian restaurants. In the fall of 1994, a facelift was planned for the restaurant.

Duggan’s Boulevard Grill

Bill Duggan died on January 13, 1996, at the age of 72. At this point it may be that chef David Ariz became the sole owner. On December 1, 1996, an ad for Duggan’s Boulevard Grill appeared in the Minneapolis Tribune, promising a redesigned dining room and bar and advertising for all staff positions. The mascot for this new iteration of Duggan’s appears to be a dog serving a plate of spaghetti…

On October 5, 1997, this very personal ad appeared in the wantads:

Yes I know. We’re looking for Cooks too. Isn’t everyone?? We pay the same as everyone, have the same equipment & wear the same outfits. Why work for us? We’re an independent w/the chef as the owner. He works like a dog all week and asks little of his co-workers. He enjoys a variety of music, has a weird sense of humor & enjoys Premium beer. He’ll improve your kitchen knowledge, remember your B-day and have an occasional brew with you. His name is Dave Ariz. (Minneapolis Tribune)

One of Duggan’s Boulevard Grill’s legacies was the outdoor patio, so popular now at Bunny’s.

Duggan’s Boulevard Grill closed on December 31, 1998.

BUNNY’S

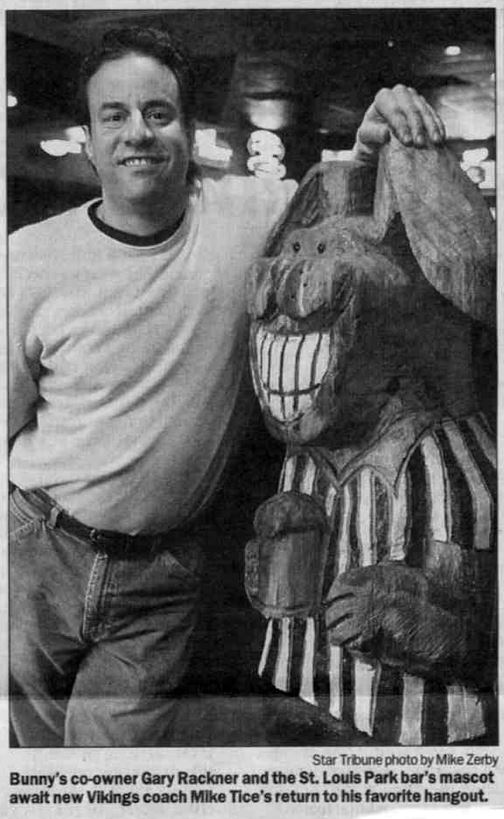

Bunny’s was started in 1934 at 4730 Excelsior Blvd. That site had to be vacated by the end of 1998 to make way for Excelsior and Grand. In January 1999 owner Gary Rackner and his new business partner, Steve Koch, moved Bunny’s Bar and Grill to the old Duggan’s site. It was a great way to preserve both the business and the building. In honor of Sherman Rackner, Gary’s father and original business partner, the back bar was named “Sherm’s.” Despite the smoking ban enforced on bars by the Freedom to Breathe Act beginning on October 1, 2007, Bunny’s is thriving!