St. Louis Park has had three McDonald’s restaurants over the years.

Lake Street

The McDonald’s at 6320 Lake Street in St. Louis Park is an iconic place in the minds of the people of the Park, and especially alumni of St. Louis Park High School. Located just across the railroad tracks, it tantalized countless students to eschew the cafeteria fare for the taste of a burger and fries. How many of those students knew of the drama that ensued before their restaurant of choice was built?

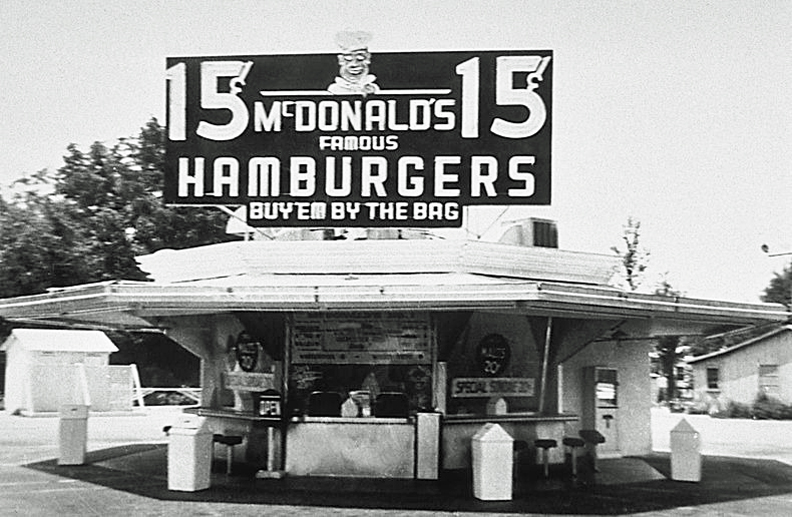

Although the idea of the hamburger stand was not new, McDonald’s promised burgers for 15 cents in a 25 cent market. Ray Kroc had perfected the art of mechanizing the hamburger-making process, making it possible to produce and sell them at lightning speed.

JIM ZIEN

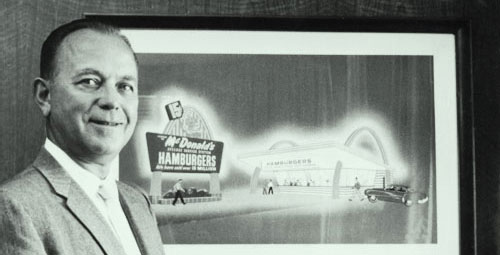

Obtaining a McDonald’s franchise meant getting a license to print money, and in 1957 one such franchise belonged to James D. Zien, the owner of the Criterion restaurant on University Ave. in St. Paul, and Zien’s brother-in-law, Sim Heller. Although the Criterion was a fancy, white-tablecloth restaurant, Zien had witnessed the immediate success of Minnesota’s first McDonald’s at 2075 Snelling Ave. in Roseville (#63 in the country) and saw the possibilities. That store was opened by David and Deborah Crimmins on September 7, 1957, according to a document issued by the McDonald’s Corporation in 1994 that listed store openings by date and location from 1948 to 1961. This information was provided to us by researcher Edwin Schlecter.

Zien was an entrepreneur. Owning the Criterion (which he sold in 1962), was almost a sideline to his main business; by 1958 he owned seven small town movie theaters. His son Peter explains:

Yes, dad was in the movie house business both before and after his service in WWII. I do not know their locations. He did share that his partners sold some of his interests while he was stationed abroad, as they didn’t think he’d come back alive! He shared stories with me about how he would have a kid bicycle some of the movies between his theaters. We also have a great picture of my father, uncle Sim, an unknown gentleman, and Judy Garland. Date unknown, but dad and Judy look young, maybe late 1930s? Even in his 80s, dad still loved watching Three Stooges shorts, telling me how he showed them in his theaters for his own enjoyment!

Zien had a unique take on advertising: “We would put banners on automobiles advertising pictures and drive through the town all day. Advertising was just in my blood.” (Love, p. 215)

FALSE START ON CEDAR LAKE ROAD

It was no accident that Jim Zien set his sights on St. Louis Park for his first franchise. His son Peter explains:

My uncle Sim and Aunt Ruth (dad’s older sister) lived in St. Louis Park. Dad loved the area and saw the potential with its proximity to schools and residences. Dad was a big believer in finding locations near private residences. He told me about taking Ray up in a helicopter to show him how many homes circled his proposed Nicollet Ave. location, which turned out to be McDonald’s first million dollar store in Minnesota (possibly company-wide, can’t confirm).

Zien’s first choice for his franchise was not Lake Street however, but the southeast corner of Cedar Lake Road and Nevada Ave. On August 7, 1957, he and attorney D.D. Wozniak went to a meeting of the Planning Commission to request a special permit to build a 30′ by 30′ building on a site that was 102′ deep by 150′ wide. There would be no facilities for sitting while eating, and the store would be open from 111 am to 11 pm.

The property was owned by Wallace T. Bruce, who had built the portion of the Westwood Shopping Center that was east of Louisiana Ave. in 1954. Bruce also owned the property from Louisiana to Nevada Avenues, and explained his plans to expand the shopping center. He thought that “the location of a traffic generating business such as the proposed drive-in is just what is needed. Some estimates have indicated 300,000 cars per year for such a drive-in business.” In other words, while most proposed development meets opposition because of the increase in traffic, Bruce was hoping that the drive-in would stimulate commercial interest in the area.

The Planning Commission was not as enthusiastic about the idea. It was pointed out that “the proposed shopping center has not been planned as to the building mass, parking, traffic, cub cuts or how the proposed drive-in will fit.” The request was “deferred pending further information consisting of a plot plan for the entire parcel owned by Mr. Bruce including traffic and parking with the suggestion that the drive-in be located at the east end where it will be adjacent to two major streets and such effect will be transferred to adjacent commercial property rather than residential.”

It was apparent that this information was not going to be available soon. As it turned out, the portion of Westwood Shopping center that was east of Louisiana was not built until 1964. And the southeast corner of Cedar Lake Road and Nevada eventually became an apartment complex, built in 1967.

TAKE TWO: LAKE STREET

Abandoning the location that Wallace Bruce had probably promoted to him, Zien looked for another property in St. Louis Park. This time he looked to the corner of West Lake Street and Dakota Ave., which, at the time, was a very viable commercial hub.

- On the southwest corner was C. Ed Christy’s gas station and sporting goods store, and institution for decades.

- Behind Christy’s at 3424 Dakota was the 55426 Post Office.

- On the northwest corner there were several stores, such as Park Drug, Home Hardware, and Palm’s Bakery

- East on Lake Street about a half a block was the St. Louis Park Community Center, which was the hub of activity for young people before the Rec Center was built.

- Just east of the proposed site was a two-business storefront that housed Scherling-Pletsch Photography and a variety of hobby and convenience stores. This building was later razed to expand the McDonald’s parking lot.

- Across Lake Street on the southeast corner was Bob’s Standard gas station

On October 23, 1957, Zien again went before the Planning Commission for a special permit to build the drive-in. The special permit was required because it would be within 200 feet of a residential district and within 300 feet of a public school. Zien presented the plat, explaining that the parking lot would be black-topped, a 20 foot setback would be maintained, and a sidewalk would be installed. One commissioner mentioned that “school officials are concerned about attracting students away from the building; however, it was brought out that the land is commercially zoned and any use made of it would have some attraction.” It was determined that the proposed use “will not create an unacceptable condition” and the request was approved.

On October 28, 1957, based on the positive report by the Planning Commission, the City Council approved the Special Permit to construct the restaurant as a matter of routine. The drive-in would cost $40,000 for the building and blacktopping the parking lot, and $20,000 for equipment. The item was buried on Page 15 the October 31 issue of the St. Louis Park Dispatch in the weekly roundup of Council actions. The Dispatch’s report read:

Special Permit for a McDonald system food drive-in at Dakota Ave. and W. Lake St. was granted James Zien. The establishment will serve prepared food to customers who would either take it home or eat in their cars, but “car hops” will not be used, the council was told. In answer to a letter from Supt. of Schools Harold Enestvedt, a company representative told councilmen presence of the drive-in would not make the problem of students congregating at the business district any more acute.

On November 4, 1957, the Council approved the building permit.

With special permit and building permit in hand, Zien arranged to purchase the land from Mrs. C. Ed Christy for $25,000.

Nothing was reported about the issue by the Dispatch when reporting on the meeting of November 11, 1957.

ALL HECK BREAKS LOOSE

But on November 18, 1957, a delegation of critics descended on the City Council to protest the approval of the permit. Their spokesman was Leo J. Schultz of 3125 Dakota Ave., who cited “safety, litter, traffic hazard and proximity to the senior high school” as reasons to rescind the permit. He presented petitions of residents and businessmen in opposition to the drive-in, which was planned for a corner where students already congregated. The most common fear was that students would pass up school lunches that were “much better for them.” The Council agreed to defer the matter for one week, while Councilman Gene Schadow and representatives of the petitioners met with Zien to work out some of the objections.

Also on November 18, Zien’s request to erect a 26 by 17 ft. sign at the site was approved. Opposing the “towering, blinking” sign was Councilman Ken Wolfe, who said, “That’s a monstrosity of a sign and it dwarfs the building. It’s something I would not want to live with.” Zien promised that he would eliminate the blinking lights “if they prove obnoxious.” Unfortunately we do not have a picture of the sign.

Between November 18 and November 25, Zien did meet with Schultz; Art Meyers, the President of the Chamber of Commerce; Schadow, and Superintendent Enestvedt. Schadow reported that Zien reacted favorably to the group’s offer to find another site “more satisfactory to everyone concerned.”

The Council meeting of November 25, 1957, was no quieter. Myers questioned the attendance of Councilman Herbert Davis at a planning commission meeting when the permit was discussed. Davis was a member of the commission; although he had been at the meeting, he said he had left before the issue of the McDonald’s permit was discussed. Tempers flared between the two men, with Meyers apparently accusing Davis of a conflict of interest?

The Councilmen referred the matter back to the Planning Commission, despite the opinion of City Attorney Edmund Montgomery that a legally-issued permit could not be rescinded.

The Dispatch reported on November 28, 1957, that:

Mr. Schultz earlier had quoted Mr. Zien as stating he expected to net $200,000 annually at the drive-in with the average meal costing 60 cents. It was figured that would represent serving 1,000 meals a day.

“If he serves 1,000 meals a day I’ll eat the whole building,” Councilman Kenneth Wolfe commented later.

“If he does that much business we ought to open a municipal drive-in,” Councilman Schadow said. “Or else there will be another request for a similar permit in here, and it will be mine!” he added.

There was no Council meeting on December 2, 1957.

Elections were held on December 3, 1957; a new City Council would take office on January 13, 1958.

AN UNPRECEDENTED RE-REVIEW BY THE PLANNING COMMISSION

The Planning Commission revisited the special permit at its meeting of December 4, 1957. The Commission opened the discussion up to the public. Zien and his attorney Hyman Edleman said that a contract for deed to purchase the property was complete, contracts to start construction were signed, and some work was already underway. Attorney Herman Ratelle stated that the drive-in should not be permitted so near the high school and that the intersection was already congested. Superintendent Enestvedt said that local businessmen often called the school or police to complain about students hanging around in the area, but action was temporary unless a policeman could be assigned to the area full time. He opined that the drive-in would “tend to aggravate this problem.” He noted that students at the Junior High were restricted to the building to prevent the problem.

The president of the Senior High PTA stated that the business would provide a new meeting place or hang out, not only for the high school students but other young people. This was not considered to be in the best interest of the “general welfare, health or morals” of the community, and the PTA voted to oppose the drive-in.

A Mr. Schultz complained that the procedure for informing the public of such developments was inadequate. He also voiced his concern about trash.

Zien said that he intended to serve 900 meals every day, or one every 48 seconds, at 60 cents each.

Art Meyers presented a large diagram of the intersection, showing traaffic volume counts taken on December 3 and 4 during the after school hours. The data was taken by “interested persons.” Meyers opined that the drive-in would generate traffic that would make the already-busy corner unacceptable.

City attorney E.T. Montgomery declared that a request for a special use permit could legally be returned by the Council for reconsideration by the Planning Commission.

After a lengthy discussion it was moved that, based on the traffic count information provided, the drive-in would create a traffic hazard at the intersection. Thus the commission recommended to the Council that the permit be revoked, provided that the City Council has a traffic survey made to substantiate the data given to the Planning Commission.

In the December 5, 1957, issue of the Dispatch it was reported that Meyers continued his “bitter attack” on the City Council. “This deal smells to high heaven,” he charged. “Not one deal in an entire year has been shoved through the planning commission and council like this one was. It was engineered so beautifully and all the loopholes were blocked so nicely that the people didn’t have a chance in the world to know what was going on.” He said he was acting on behalf of the Chamber of Commerce because he has had “numerous calls from Chamber members wondering what is going on. I’m not trying to implicate anyone on the council but just trying to get to the bottom of this thing.”

[Meyers] revealed that four Councilmen were told of plans to erect an office building on the site before the drive-in permit was granted. He said had the drive-in been rejected on the basis of health, welfare and safety reasons, the office building would have been built there.

“What’s best for the city, another hamburger joint or an office building?” he said. The Chamber president said the one story, 10,000 square foot office building would have accommodated 60 employees. It would have been built at a cost of $150,000, he said.

“The office building would have increased our tax base much more than this $35,000 drive-in, and no hazards would have been created such as are being created by the drive-in,” he said.

He said that Councilmen Schadow, Wolfe, Davis and Ehrenberg were aware of the “second-choice” plans for the land … He said they all were notified by telephone.

“If one of them had moved to table this drive-in requests, the people would have had a chance to find out what was going on and to voice their opinions. But no, everything rolled along smoothly and the deal went right on through without a ripple of delay. It certainly was well engineered. In fact the permit was given Mr. Zien on the Thursday before it was formally granted by the council,” he charged.

Also in the December 5, 1957, issue of the Dispatch was an Editorial that started out,

St. Louis Park’s city council this week finds itself in one of its worst jackpots. The president of the local Chamber of Commerce has unleashed an unprecedented blast at the council. School officials are disturbed.

Council pulled the lever on the jackpot by granting a special permit for a food drive-in near the senior high school and not far from the junior high school. When the wheels stopped spinning, three lemons showed up.

After spelling out the facts of the case, and concluding that legally little could be done, it ended:

The only hope for the objectors lies in the chance the drive-in operator may decide to build elsewhere rather than try to do business in a hostile neighborhood.

At the Council meeting of December 9, 1957, Councilman Torval Jorvig moved to rescind the permit, but the motion died for lack of a second. The council then voted to defer action until its meeting of December 23, pending analysis of a traffic study of the intersection. Meyers and Schultz provided their own data on traffic conditions, but Hyman Edelman, Zien’s attorney, said that any traffic problems could be “easily controlled. There will be no real menace to anybody. Let the action stand as it is.” [To this day there is only a four-way stop at the intersection.] Edelman continued, “It would be a tragic thing for every citizen of the Park if the idea was disseminated that permits are issued businessmen who then find that they are subject to being recalled.” Zien agreed to suspend building until a final decision was reached.

A sidebar in the December 12, 1957, Dispatch demonstrated how desperate the Chamber was to defeat the drive-in:

During discussion of the controversial Zien drive-in permit before the city council Monday night, Art Meyers arose and said: “I will give $5,000 for a library in St. Louis Park if something else can be done on that corner.”

At the December 23, 1957 (reported on by the Dispatch on January 2, 1958), another wrinkle was added when Mrs. Henry P. Morris, an unsuccessful candidate for City Council (and indeed the first woman to actively campaign for Council), noted, “I was in the audience the night the permit was issued unanimously. In fact I was the only audience. I was the only one left at the time this came up. Nobody opposed it. Consider what would be the effect on future people bringing business into the Park.”

The Council once again voted that the permit be postponed, with Jorvig and Wolfe favoring suspension and Davis and Robert Ehrenberg opposing the delay. Mayor Russell Fernstrom broke the tie by voting for postponement. The same arguments were given, with Jorvig saying “I feel we all made a mistake,” and Ehrenberg arguing that rescinding the permit would leave permit holders insecure about whether their permits would be revoked.

MORE VEHEMENCE AND A FINAL VOTE

At the January 13, 1958, meeting the Council heard from angry residents, including Mrs. Howard George of 2705 Lynn Ave., who said that not one of the parents of high school students favored the location of the drive-in. She also said “Sgt. Clyde Sorenson [not yet Chief of Police] said the drive-in would bring increased police activity to the area.” Mrs. George noted that a permit to construct an identical structure at Nevada Ave. and Cedar Lake Road had been denied the summer before, implying that “we have a first class citizenry and a second class citizenry. Those with money get consideration – those without – do not.”

Speaking for the restaurant was Don Conelly, representing McDonald’s in Chicago. He pointed out that the drive-in would not “employ women, would have no car hops, no outside facilities conducive to loitering, no alcohol, cigarettes or pin ball machines and generally – just sell hamburgers.”

Another vote was taken to decide whether to rescind the permit. Voting against the drive-in were Jorvig and newly-elected Councilmen Herman Bolmgren, and Dallas C. “Tex” Messer. Messer was concerned about the future of the site if the McDonald’s franchised failed.

Voting to lift the temporary suspension of the permit were Councilmen Davis, Wolfe, and Ehrenberg. New Mayor Herbert Lefler had to break the tie, voting not to rescind the permit even though the Planning Commission recommended revocation. Lefler qualified his decision by saying, “I’m not in sympathy with drive-ins but this one has been duly processed. The issue is no longer the drive-in, but the seriousness of revoking permits which would leave a precedent for more trouble in the future.”

One of the last volleys in the war came in an apparently unsigned Letter to the Editor, published on January 16, 1958. McDonald’s was feared to be:

a monument of neon and tile commemorating the shortsightedness of our Planning Commission and the unreasoning obstinacy on the part of three councilmen and a mayor.

It wasn’t quite over. An editorial in the January 23, 1958, issue of the Dispatch was entitled “Both Arguments Have Their Merits,” and the language was fanciful:

The mayor’s vote decided the issue, but you can be sure the opposition won’t let it be forgotten. Vociferous objectors already are calling names, charging discrimination and threatening retaliation … especially at the polls in future city elections. Some are so upset by council’s action one begins to wonder if their interest in the drive-in site is not deeper than appears on the surface.

Their voiced objections to the drive-in, especially to them, are very real and we can understand their concern. They envision a teen age hang-out at the site, predict increased police activity in the area and fear the business will create a nuisance.

But the editorial went on to say that the point was well taken that to revoke the permit would set a bad precedent and work a hardship on the permit holder, who had already expended $25,000 to acquire the property and make arrangements for construction.

And then the war of words went silent, and there was nary a sound about the impending doom going up on the corner of Lake and Wooddale.

McDONALD’S OPENS

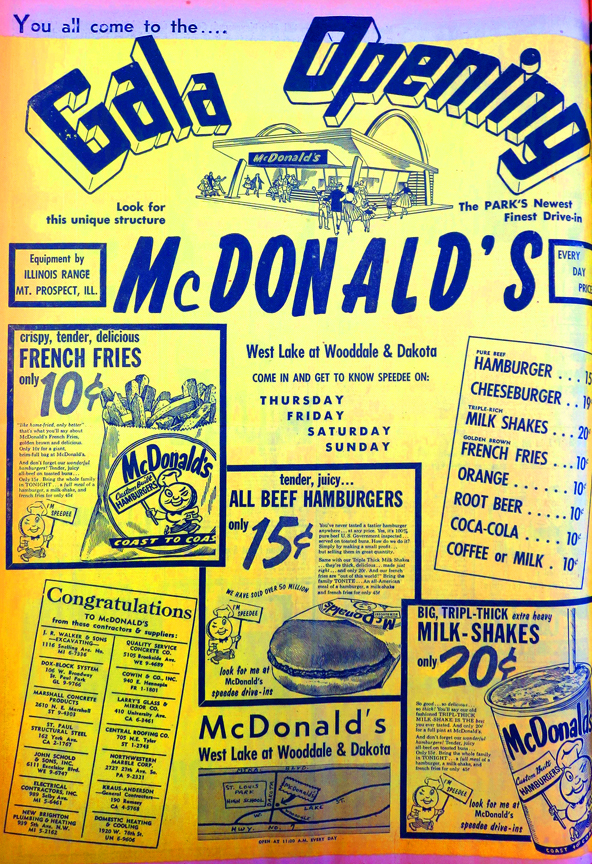

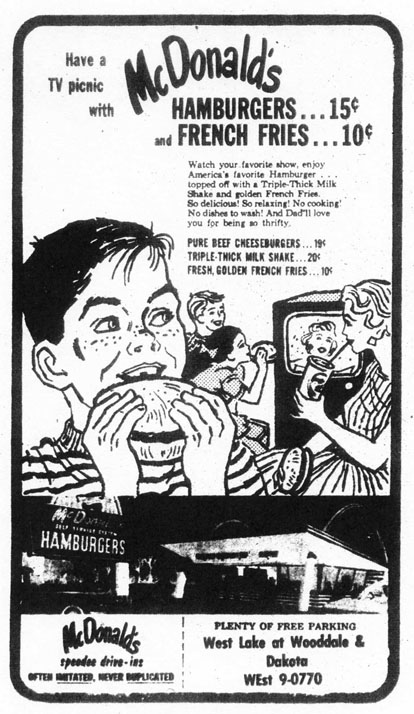

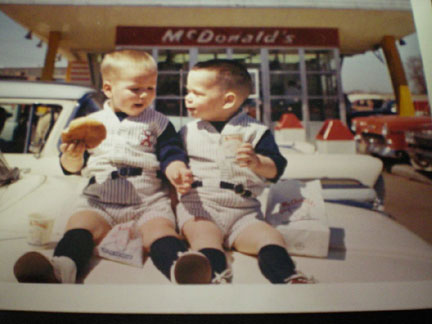

Although the store’s official soft opening was on June 3, 1958, the Gala Grand Opening was held on June 12-15, 1958. It was Park’s first, the state’s second, and the world’s 93rd McDonald’s ever built. Despite changes, it still carries the number 93.

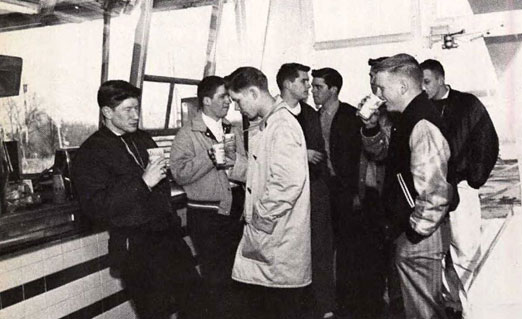

Ray Kroc and future McDonald’s CEO Fred Turner were present on opening day, along with 20 employees (one account cites 40). Many of them were announcers-in-training from Brown Institute and they would practice their radio voices. Women were not allowed in the building. To discourage loitering, there was no seating. The line was two deep, a block long, for hours at a time. The weekend take was about $23,000, four times the amount projected. Zien spent a reported $12,000 for his sign, more than most houses cost in 1958. Dale Lapakko remembers the first thing on the sign was “100 Sold.”

The on-site manager at the St. Louis Park store was Rollie Smith, husband of Joan Smith. Zien split the profits evenly with Smith, and Smith got a $12,000 bonus in the first year. Zien knew Smith through Smith’s wife Joan, who played the Hammond organ at Zien’s Criterion Restaurant. Years later Joan would divorce Smith and marry Ray Kroc, but Rollie Smith remained in the McDonald’s family; Zien and Smith went in as equal partners in a franchise in Rapid City, South Dakota, and went on to owning several franchises.

JIM ZIEN’S ADVERTISING

From the start, Zien wanted to agressively advertise the new drive-in and not wait for word-of-mouth. He decided to spend 3 percent of sales on advertising, and persuaded Patty Crimmins, his counterpart in St. Paul, to establish a cooperative advertising fund. Each contributed $600 every month toward the fund, and with this war chest available, Zien hired Jaffe, Naughton and Rich, a local advertising agency, to produce a sophisticated ad campaign that would be more than just print ads.

Al Jaffe, one of the firm’s partners, couldn’t understand why anyone would want to pay $1,200 a month to advertise a hamburger stand. “I had seen this funny-looking store going up, and I wondered why someone would want to desecrate the neighborhood like that. when he wanted to advertise it, I figured he knew something I didn’t.” (Love, page 215)

But rather than relying on newspaper advertising, they expanded into radio. And to do that, agency partner Sid Rich wrote a jingle that emphasized the food’s economic value:

Forty-five cents for a three-course meal

Sounds to me like that’s a steal

With the help of the jingle, Zien’s sales soared. He shared it with other franchisees for basically nothing, and soon it could be heard all over the country.

Another innovation in advertising attributed to Zien was advertising on locally-produced live kiddie shows, which were prevalent in the 1950s and ’60s. Hosts of the shows made the pitches, so production costs were minimal. Unfortunately, the Love book does not give us the names of the shows. With Zien the owner of the exclusive rights to the Minneapolis market, he could do no wrong. Kroc stopped giving out exclusive rights by the early ’60s. (Love p. 224)

Peter Zien, who was born in 1962, remembers doing the rounds:

Dad owned a number of stores – 5 or 7 – in the Twin Cities. As early as 5 years old, I remember dad taking me on “the rounds” every Saturday. We would pop in to his stores unannounced and evaluate service, food quality and head counts. I also helped by eating a burger or fries or a shake at each store! I looked forward to these visits and remember the wonderful smells and perfectly cleaned stainless steel counters and processing equipment in the back.

By 1959 the members of the City Council were probably wishing they’d had a piece of the new burger joint: it did over $315,000 in business that year. In 1960 our store did more business than any other in the then-228 store chain. And in one month it broke the company-wide monthly total by bringing in $37,262. St. Louis Park loved its burgers, fries, and shakes for their ridiculously low prices.

Al Hartman remembers the early days:

Since the store originally opened in the summer, there was no enclosure. When cold weather came they installed the glass enclosure and doors but still people were in line outside of the building. It was hard to tell if the cold weather enclosure was the original plan but it must’ve been. There were rudimentary built-in ceramic tile uncomfortable benches on the sides of the building. The benches were not cleaned very often, at least when I hung out there as a kid during a late 1950s summer, and ketchup, mustard, etc. spills were on them most of the time. The guys working there peeled the potatoes, subsequently running each of them through a large slicer to make the fries.

Competition for the local drive-in business in the 1950s and ’60s was fierce: there was even a so-called “Drive-In Point” full of them by Lake Calhoun. Henry’s, a local hamburger chain, had locations in Crystal, Bloomington, and Richfield in 1961, but apparently not in the Park. Porky’s had locations by Lake Calhoun and St. Paul.

An article from the February 10, 1965, issue of the St. Louis Park High Echo reported that the store sold about 24,000 hamburgers per week and over 1 1/4 million per year. The French fry count was 16,000 orders per week, or 800,000 bags per year. “Surprisingly, by far the largest share of McDonald’s customers are adults who provide 80 to 85% of their total business.”

By 1966 it was okay for women to work at McDonald’s, as long as you were married – presumably married women wouldn’t cause much of a distraction to those high schoolers.

EXIT JIM ZIEN

In 1969 Zien sold his stores back to corporate and moved to La Jolla, California, where he owned a couple of franchises in San Diego. He became a regional manager, and, with Paul Schrage, developed and tested the first Playland. Peter Zien remembers that his dad regretted the pit of play balls, which had to be cleaned frequently because a kid or two would … have a little too much fun. We have Jim Zien to thank for his persistence and vision! Zien passed away at age 88 in 2001, and always spoke about McDonald’s fondly.

In about 1969-1972, all of the McDonald’s stores were remodeled and our beloved Golden Arches were removed, replaced with a brown brick building with a mansard roof. The original sign was replaced at the same time. At one time there were pictures of the restaurant from the fifties, sixties, and seventies on the walls, but it is a mystery as to what happened to them.

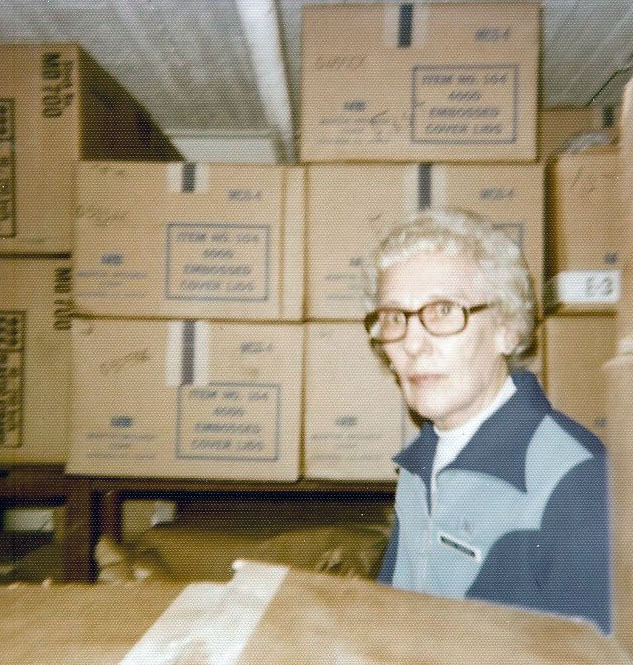

HAZEL THE DAY LADY

One of the best-remembered employees was Hazel Garton, who started working here in 1971. Hazel lived behind the dentist across from the Roller Gardens. When Caprice Lantto-Walker used her bathroom she was amazed that Hazel had wallpapered it with the colorful paper tray liners from McDonald’s! Hazel was dedicated to McDonald’s and had a collection of memorabilia, including glasses, ashtrays, toys, books, and other McDonald’s promotional items. Judy Andersen Hogan took this picture of Hazel on 15 Cent Hamburger Day, April 1975. Hazel passed away on October 7, 1992.

McDONALD’S VS. MAZIE OTTO

All those dire prognostications of high school students sneaking over to McDonald’s for lunch instead of eating the delicious cafeteria fare came true, of course. A wry 1979 article in the SLP Sun by R.T. Rybak (who later became the Mayor of Minneapolis) had the headline:

She does it all for you: Mazie Otto launches Big Mac attack

The article told of how the new director of St. Louis Park schools food services was determined to take on the competition from McDonald’s, which “has done a brisk lunchtime business as hungry students have illegally left school grounds to sample the famous hamburgers and fries. The traffic from St. Louis Park High has, in fact, been so heavy over the years that McDonald’s once sponsored an appreciation dance at the school.” Mazie’s predecessor, Billie Lee, began a fast food section at the school, offering hamburgers, fries, and pizza. Otto planned to increase those selections, carrying roast beef sandwiches, corned beef on rye, kosher pickles, and other “finger foods.” Otto said, “Today’s kids like fast foods. We know the kids should eat vegetables and we put them on the menu. But there is nothing that can force them to eat them. We know our competition is McDonald’s and we have been pretty successful, especially in winter when the kids don’t want to go out into the cold. But if they want to go eat at McDonald’s or if they want to go across the street to smoke, there is nothing you can do to stop them.” Mazie “rolled out heavy artillery in her fight against the fast food giant,” coming out swinging with menus of pizza and tacos. But she remained philosophical. “Kids never appreciate school food. But once they leave it, they always want to come back.

In June 1983 the restaurant celebrated its 25th Anniversary with a visit from Ronald McDonald, magic and juggling acts, a performance by the St. Louis Park Community Brass Band, gypsy palm reading, face painting, and a performance by the Salvation Army Kitchen Band, a group of senior citizens who played kitchen instruments. Also on hand was Sim Heller, one of the original owners of the store, and Greg Witry, the then-current manager.

A NEW LOOK

In October 2000 the building was razed by owner Ken Darula in order to build a larger facility. Al Hartman says, “When the building was razed there were rumors floating around that they had found quite a bit of money stashed in a wall in the basement implying an employee was building a nest egg but nothing was ever substantiated.” A news report said that 50 employees would be added to the larger store.

In 2016 our Lake Street store was put in the spotlight with the book Ray & Joan: The Man Who Made the McDonald’s Fortune and the Woman Who Gave it all Away by Lisa Napoli. The book focused on the role that Ray Kroc’s third wife Joan played in his life and how she donated his fortune, but provides a comprehensive history of McDonald’s itself.

Also in 2016, a major motion picture called The Founder, starring Michael Keaton as Ray Kroc, made its debut. The film took some dramatic liberties with the facts, as explained by Ms. Napoli on her website

It should be noted that references to the “Minneapolis” store in the early days were undoubtedly about St. Louis Park’s store; as seen below, Minneapolis proper did not have a McDonald’s until after 1961.

Knollwood

A small McDonald’s was located in Knollwood Mall from 1983 to 1997. When it came in there was considerable controversy, as the owners wanted it to be in the main part of the mall and not in the food court. The city tried to block it, saying that it was against the terms of the PUD that was developed for the mall in 1977. The issue caused the city to revisit the PUD, but eventually McDonald’s ended up in the food court.

Park Commons

A McDonald’s opened in Park Commons, 5200 Excelsior Blvd., on Friday, October 14, 1994. It was expanded in 2012.

The First McDonald’s Stores in Minnesota

- 2075 North Snelling Ave., Roseville, September 7, 1957.

- 6320 W. Lake Street, St. Louis Park, June 3, 1958.

- 4605 Central Ave., Columbia Heights, June 30, 1959.

- 1620 Service Drive, Winona, MN, September 22, 1959

- 8040 Nicollet Ave., Bloomington, December 27, 1960

- 1273 So. Robert Street, West St. Paul, May 24, 1961

- 1165 Prosperity Ave., St. Paul, November 28, 1961

- 2070 County Road E, White Bear Lake

- 5400 West Broadway, Crystal

- 5831 University Ave., Fridley

- 720 Winnetka Ave. No., Golden Valley

- 407 15th Ave. SE, Minneapolis

- 551 Jefferson Street, St. Paul

- 701 Rhine Street, Mankato, Spring 1967

- 1116 No. Broadway, Rochester, July 9, 1968

- 1009 West Oakland Ave., Austin, August 12, 1969

Some McDonald’s History

McDonald’s was founded in 1940 as a barbeque restaurant in San Bernardino, California, by Richard and Maurice McDonald.

In 1948 the barbeque was converted into a hamburger drive-in. (That location was demolished in 1976.)

The first mascot of McDonald’s was Spee-Dee.

The Golden Arches first appeared when the store in Phoenix opened in March 1953. The company first trademarked the Golden Arches in 1961, although the look of them changed over the years.

The first franchised restaurant was opened in Des Plaines, Illinois, on April 15, 1955, by businessman Ray Kroc. It was the ninth McDonald’s restaurant overall.

While in the Twin Cities arranging for the construction of the St. Louis Park McDonald’s on Lake Street, Ray Kroc met his future wife Joan, who played the organ at the Criterion Restaurant in St. Paul. They eventually married; read the story in the book in Lisa Napoli’s book Ray and Joan – there is quite a bit of material about the brouhaha surrounding our Lake Street store!

In 1961 Ray Kroc bought all rights to the McDonald’s concept from the McDonald’s brothers for $2.7 million. On May 4, 1961, McDonald’s first filed for a U.S. trademark on the name “McDonald’s” with the description “Drive-In Restaurant Services.”

Ronald McDonald was created and first played by Willard Scott in 1963. Ronald had totally replaced Speedee by 1967.

SOURCES

Many thanks to the City of St. Louis Park for access to Planning Commission minutes.

Articles

Hearing Set Nov. 11 on Hebrew School in Park: St. Louis Park Dispatch, October 31, 1957

Huge Sign For Drive-In Approved: Dispatch, November 7, 1957

Fight Brews On Permit For Drive-In: Dispatch, November 21, 1957

Planners Get Drive-In Squabble: Dispatch, November 28, 1957

Chamber President Presses Attack On City Council In Fight Over Drive-In Permit: Dispatch, December 5, 1957

The Case Of The Disputed Drive-In: Editorial, Dispatch, December 5, 1957

City Defers Final Action On Drive-In: Dispatch, December 12, 1957

New Mayor Inherits Hot Drive-In Issue: Dispatch, January 2, 1958

Drive-In Hurdles Council: Dispatch, January 16, 1958

Citizen Calls Mayor, Council’s Stand On Drive-In “Obstinate” – Letter to the Editor: Dispatch, January 23, 1958

Both Arguments Have Their Merits: Editorial in the Dispatch, January 23, 1958

Sign, Burgers In Contract at Zien Drive-In: Dispatch, June 12, 1958

Food-Famished Fans of McDonald’s Feast on Tons of Fries, Hamburgers: St. Louis Park Echo, February 10, 1965

She does it all for you – Mazie Otto Launches Big Mac attack by R.T. Rybak: St. Louis Park Sun, August 22, 1979

Lake Street McDonald’s marks 25th anniversary: St. Louis Park Sailor, June 27, 1983

McDonald’s fallen arches will be built on same site: St. Louis Park Sun-Sailor, October 11, 2000

Books

Ray and Joan: The Man Who Made the McDonald’s Fortune and the Woman Who Gave it all Away, by Lisa Napoli, 2016

McDonalds Behind the Arches, by John F. Love, 1986