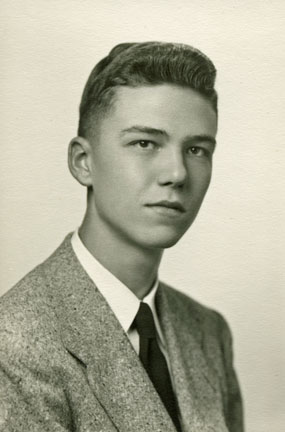

This is the story of a young man who had the world on a string, with endless possibilities, only to have the rug pulled out from under him. This is the story of how that young man refused to give up, going on to live an interesting, productive life. This is the story of H. LeRoy deBoom.

EARLY YEARS

Henry and Verna deBoom first came to St. Louis Park in 1937, first living at 4021 Xenwood Ave. in a house that is no longer there. Henry worked for the Minneapolis Artificial Limb Co. Sometime after 1949 they moved to 3945 Zarthan Ave.

One can find articles about LeRoy’s early years all through the St. Louis Park Dispatch and the St. Louis Park High School Echo in the 1940s and ‘50s. He was an exceptionally smart, active kid. He was a crossing guard at Brookside School back in the days when children crossed Highway 100 by foot to get to school. He was a paperboy since 1947, with routes covering practically the whole South Side. He was a Boy Scout in a Minneapolis troop, ushering with the first aid group at Memorial Stadium.

And he was a scholar – since seventh grade he competed in the Minneapolis Star’s Information and World Affairs test. He was grade champion his first year, and in eighth grade he was the youngest participant. In ninth grade he had the highest score of all freshmen competitors. He was a finalist for the fourth time in his junior year; “I guess I’m just a hardy perennial,” he quipped in the May 8, 1951 Echo. On May 12, 1952, LeRoy received a Rand-McNally Atlas and a biographical dictionary for placing 7-25 on the test at the Nicollet Hotel.

HIGH SCHOOL ACCOMPLISHMENTS

As a freshman in 1949-50, LeRoy was a member of the student council, glee club and chorus, and a reporter for the Echo.

LeRoy was honored by the Minneapolis Star and Tribune Scholarship Committee for three years in recognition of scholarship, citizenship, and ability as a carrier salesman:

- 1949: Honorable Mention

- 1950: Award Winner

- 1951: Honorable Mention

In the summer of 1950, LeRoy, along with Bill Dean and Corwin Reed, made a trip to the Boy Scout Jamboree at Valley Forge. LeRoy was awarded the trip free of charge from the Minneapolis Star. The trip included stops at Chicago, New York, Philadelphia and Washington. None of the boys had ever traveled to the East before. Plans were to build a model city and to hear a special address from President Truman. In typical journalist-to-be fashion, LeRoy sent dispatches about the trip back to the paper, which were printed.

In February 1951, LeRoy represented the Boy Scouts at the Quiz of the Twin Cities and successfully answered all the questions. For his efforts he received $12 and helped Minneapolis win the contest. (as reported in the Echo)

Despite his height of 6′ 6″, LeRoy confessed to not being a very coordinated athlete, but his big interest was in journalism. In his Junior year (1950-51) he was the third page editor of the Echo, and the paper was rated All-American by the National Scholastic Press Association, the first time in Park history.

That same year the Echo received a national award for outstanding contribution to tuberculosis education. LeRoy was part of the delegation from Park that attended the annual High School Press Project meeting at Glen Lake Sanitarium in November 1951. Amid this responsibility, he was also on the debate team and a member of Hi-Y.

One of the highest honors, Editor of the Echo, was bestowed upon LeRoy in May 1951 for the 1951-52 school year. The paper won All-American for a second year and the Dillman Award for the third year.

One of LeRoy’s most memorable moments of his senior year is when a bunch of Park kids were in Anoka for a football game. Somehow their signals got crossed as to where to catch the bus back. LeRoy ran four blocks trying to catch the bus, but it took off and he had to run the four blocks back. The kids camped out at the police station and did the Hokey Pokey until their parents could come and rescue them.

In October 1951, the Echo reported that LeRoy and classmate Dick Buchheit had been chosen Junior Rotarians for the month of October by the St. Louis Park Rotary and the school administration. They would be guests at all the Club’s dinner meetings that month. LeRoy remembers that the dinners were at Culbertson’s and that they ate filet mignon – the first time he knew that beef didn’t always come ground!

Also in October 1951, LeRoy was elected by the student council as part of Park High’s delegation to the Minnesota State High School convention in Duluth, November 1-3. Other delegates were Joan Hancock, Joan Nelson, Bud Ondich and Nancy Janes. Joan Hancock, Park’s student council president, stated “The convention will enable delegates to co-ordinate their ideas and discuss and solve their school problems with those of other delegates.” She and LeRoy were Park’s voting delegates.

Everything was buzzing along – he had been offered a full scholarship to Harvard, which he accepted. The May 22, 1952, Echo reported that he was awarded a national scholarship worth $1,050 a year and $50 a year from the Harvard Club of Minnesota, renewable for as long as seven years. He had also been offered a $900 regional scholarship to Yale, but he declined because it would have required him to work in the cafeteria.

The summer of 1952 was spent working at the Star, sending prizes to paperboys (with “Dating Game” host Jim Lange) and catching up on some math skills at West High.

TRAGEDY

And then on August 17, 1952, LeRoy started feeling ill, perhaps with the flu. On the second day, his leg buckled under him, and by the third day, he was in the hospital in an iron lung. It was polio.

Polio (poliomyelitis), a disease caused by a virus, started to become common in our area in the early 1930s. Better sanitation rendered people less immune to the virus, with the result that it became more powerful than it had ever been. The first cases were seen in the U.S. as early as 1894 and it reached epidemic proportions in about 1946. Each year the polio “season” would begin in May and peak in the early fall. Public pools were closed, civic celebrations were cancelled, and even school openings were delayed. During the epidemic, 735 lives were lost in Minnesota to the disease. Victims, usually young children, experienced atrophy of the legs and chest, which eventually caused difficulty breathing. Doctors splinted the affected extremities with plaster and wood, often causing permanent damage, and placed the patient in an iron lung respirator to assist breathing. Sister Kenney developed her own method of physical therapy. The Salk and Sabin vaccines were developed only a few years later, and by the mid 1950s the illness was virtually eliminated.

But that was too late for LeRoy. As early as August 30, 1952, he dictated a letter to his beloved Echo staff describing what he was going through. This letter is painful to read, as he is still hopeful that he’ll be able to go to Harvard, but it gives a rare insight into what it’s like in an iron lung.

This having polio is a “novel” experience to say the least. Your legs start to ache, then your arms, they they stop aching and you can’t move them. It doesn’t hurt after all that, at least for a while, but you feel rather silly. When you feel O.K. everything feels O.K. and yet all you can do is wiggle your fingers and toes. Right now I’m in an Iron Lung. It seems my chest muscles got paralyzed too, and I found myself unable to breathe fast enough and deep enough to keep myself from “feeling very uncomfortable” so they put me in the Emerson Respirator Model No. 5C Serial No. 44 which does it all for me (It’s a product of Cambridge, Mass., where I’m going next fall since my scholarship is being held in advance for me and I’ll still be able to use it.) Well anyway, this lung is a long tube that’s air tight except where my neck sticks out a little and leaks a little but theoretically it doesn’t.

By changing the air pressure inside air from the outside is alternately sucked in and pushed out and since the only way it has of entering and leaving is through my mouth, I breathe. Even with this marvelous piece of equipment I feel kind of starved for air sometimes. …

Right now I’m going into still another stage in which my muscles start coming back to life, during which process they hurt like the dickens. They seem to get real tight. I’m getting the best of care through it all, though. I get washed every day and fed pretty good although I can’t eat too much, and my folks visit me three times a day. So I’m just grinning and bearing it. Oh yes, I’m learning to breathe again. It seems you forget when you’re in a lung very long and so they take me out of the lung for short periods to practice very day. Well, enough about me [questions about the Echo]

Well, I guess this is about it. I’m getting rather tired and breakfast is coming. I know I’ve left out a lot of things which might interest you, and I know my English isn’t too good, and I can’t even sign this, but that’s the way things go when you’re in an iron lung. You’re not as efficient as you’d like to be. If some of you would like to visit me, you can come anytime. Anyone over 16 is allowed in.. You’ll have to wear a gauzed face mask, but I’ll enjoy seeing you even with that on. Hoping to hear from you.

Le Roy

The first issue of the 1952-53 Echo, dated September 2, 1952, reported that LeRoy was in General Hospital in critical condition. The Echo followed that up on September 16 with excerpts from his letter of August 30. In the December 17, 1952, Echo, he showed that he hadn’t lost his sense of humor when he wrote:

Ole General hospital is doing pretty well by me these days. I’ve been breathing, on my own, twelve hours a day and using a respirator only at night, but even twelve hours is a big improvement. It’ll be quite awhile before I can get on my own completely.

My limbs are coming along pretty well too – not any new muscles, but the ones I have are a lot more loose, and my therapist says I’ll be able to sit in a wheel chair soon.

Yours for bigger and cheaper Christmas trees.

LeRoy

In June 1953 the Echo reprinted a report LeRoy had made to the Aldersgate Advance. He was on a respirator for only three hours at night and was at the Sister Kenney Institute.

He graduated from an iron lung to a rocking bed, then to a wheelchair.

In March 1954 Park High showed they had not forgotten LeRoy by including an update in the Echo. At the time he was in a six-bed ward at the Sister Kenny Institute and could make visits home on alternate weekends. During occupational therapy LeRoy was constructing a bookcase. He held dreams of studying at the U of M, then graduate work at Harvard. Student reporter Georgiana Christman paid tribute to LeRoy’s spirit when she wrote:

Far more than a polio case, LeRoy deBoom is an individual…perhaps a finer person today than ever before. His pluck, determination, humor and personality might well serve as an example to many of us who may be more fortunate in a physical sense, but who would be hard pressed to match his courageous record.

ONWARD

When he was discharged from the hospital after 22 months he was unable to walk, and had use of only three fingers. His mother reported that he had returned home in June 1954 weighing jus 91 pounds on his 6′ 6″ frame. But his mind was clear and he was determined to go on with his life, albeit with some changes.

LeRoy’s Park High classmates continued to remember him, and he periodically submitted letters reminding students how important it was to get polio vaccinations. In the January 23, 1957, issue of the Echo, he and fellow polio victim Chuck Heinecke were interviewed. LeRoy said “It’s just like continuing to stand in the way of an oncoming car when you have the opportunity to move.” Chuck, who did not have any lasting disability, said “Never in my life have I regretted anything so much as the fact that I hadn’t had the polio shots.”

A lengthy article in the September 11, 1955, Minneapolis Sunday Tribune revealed that friends and family called him Lee, and that he had learned how to write, paint, weave, type and do leather work, and he had a diploma in speed writing. LeRoy was able to go on long drives, to the movies, weddings, and picnics. LeRoy’s father Henry deBoom was a good impromptu handyman, building the first ramp to the house, operated by ropes. Brother Jim test drove the ramp – “The chair and I ended up in a heap the first time,” Jim said, “but we’ve perfected getting down now.” Many years later, Jim’s daughters had fun working the ramp. Another unique item he built for LeRoy was a device made from steel pipe, a coat hanger, and a chair leg, which LeRoy used to grab items and scratch his head, among other things. Henry deBoom had had a mild case of polio as a child, and got up several times a night to turn LeRoy over in bed.

LeRoy’s courage was demonstrated when he decided to attend the U of M, chauffeured by his parents. These were days long before the campus was accessible to wheel chairs, and often LeRoy would have to recruit strong students to give him a lift up a flight of stairs. Logistics became too daunting after two quarters, though, and he started going to night school. He had learned to type at Sister Kenney, and his father had rigged up steel weights on pulleys to facilitate his typing. He studied accounting, and it took him several years, but he took every accounting class he could and earned an AA degree on December 11, 1961. He worked as an accountant for two companies and even had his own accounting and tax practice in the family home until his health deteriorated in 1973.

LeRoy always had an interest in community affairs, and was an active member of the Jaycees (publicity chairman in 1959), Boy Scouts, and Men’s Club at Aldersgate Church. He has also belonged to the Indoor Sports Club of Minneapolis and the Disabled Citizens Club. In fact, he was so active that an article appeared in the Dispatch in 1965 that gave his views on issues ranging from bond issues to girlie shows. Another column in the Tribune reported on his novel idea to institute Temperature Savings Days (TSD):

The idea is simple. Every winter (say from October 1 to May 1) zero would be lowered on all thermometers by 30 degrees. Thus instead of braving temperatures of 12 below zero on a given morning, we would enjoy readings of 18 above. TSD would boost the morale of Minnesotans and improve the state’s image in the rest of the nation.

LeRoy lived with his parents in Brookside; his mother died in 1996 and his father in 2000. His brother Jim moved to California, but came to visit several times a year, often bringing one or both of his daughters, who got to know the Brookside neighborhood. Jim spent every Thanksgiving with LeRoy.

Only in 2004 did LeRoy move to the Benedictine Health Center of Minneapolis, a facility that could more closely monitor his health needs. There he remained sharp, still reading the paper and writing many letters to the editor (even if some of them are only in his head). In 2012 he and his brother made it to his 60th Class Reunion, where he met up with his former classmates (including the Homecoming Queen, he pointed out). He made use of technology, both in his health care needs and in entertainment, using the building’s wifi, subscribing to Netflix, and skyping with his brother’s children and grandchildren out in California. He also helped staff members with computer issues.

LeRoy had a close relationship with his church, Aldersgate Methodist, writing a column in the newsletter called “My Window.” Singers and the bell choir would come to entertain, and his pastor visited, only to be caught in the conversations about politics and world affairs that LeRoy loved throughout his life.

PASSING

LeRoy finally succumbed to complications of polio on March 12, 2014 at age 79. His family wrote, “LeRoy had gone through so much, lived much longer and led a fuller life than thought possible. He was strong, lived with spirit and tenacity and was an inspiration to many.”

Memorials in LeRoy’s name maybe made to:

-

- Aldersgate United Methodist Church, 3801 Wooddale Ave., St. Louis Park, MN 55416

- Benedictine Health Center, 619 E. 17th Street, Minneapolis, MN 55404

- Rotary International Polio Eradication Program, www.endpolionow.org

Read LeRoy’s full obituary in the StarTribune Here.

LEGACY

LeRoy deBoom is an inspiration to those of us who complain of minor aches and pains. He’s living proof that one’s will and determination are stronger than even the most severe physical limitations. And he has certainly lived up to his surname, which is Dutch for “The Tree.”