These are only highlights in the history of the modes of mass transit that affected residents of St. Louis Park. Please contact us with additions and corrections.

Information in this document relies heavily on the books

- Transit in the Twins, by Stephen A. Kieffer, published by the Twin City Rapid Transit Company in 1958, and

- Twin Cities by Trolley, by John W. Diers and Aaron Isaacs, U of M Press, 2007.

For more information on Twin Cities streetcars, visit the Minnesota Streetcar Museum at www.trolleyride.org.

This page appears in three parts:

Part I: Minneapolis Streetcars and St. Louis Park Buses

Part II: The Como-Hopkins Streetcar Line

Part II: T.B. Walker’s St. Louis Park Streetcar Line

PART I: MINNEAPOLIS STREETCARS AND ST. LOUIS PARK BUSES

1872

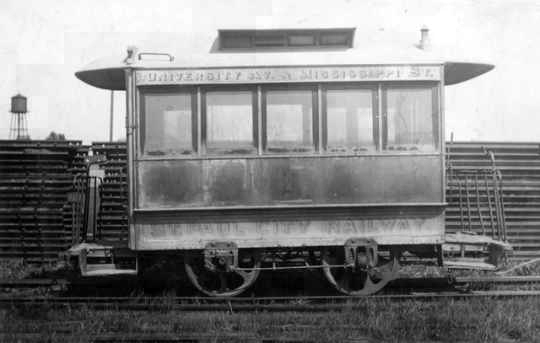

Horsecars had been operating in New York City since 1832. The first horse car trod the mud streets of St. Paul on July 15, 1872. The first route was two miles long. Capacity was 14 passengers. The St. Paul City Railway Company had six cars (dubbed “cracker boxes on wheels”) and 30 horses, operated by 14 men.

1875

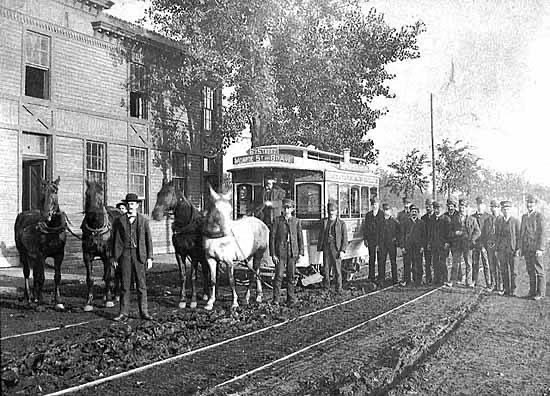

Streetcar service opened in Minneapolis on September 2, 1875. The Minneapolis Street Railway, under the leadership of Thomas Lowry (an emigrant lawyer who came to Minnesota from Illinois) built 4.37 miles of track that started at Hennepin and Washington Avenues. The ten cars, which were sometimes referred to as “Tom Lowrys,” were drawn by horses.

From MNOPEDIA:

The early Twin Cities horsecars were modest in size at just ten feet long and, at about 1,000 pounds, were equivalent in weight to the average horse. Each car could accommodate up to 14 passengers and ran at a maximum speed of six miles per hour, as mandated by city ordinances. For the comfort of riders in winter, heat was generated by a small iron stove placed in the middle of the car and the floor was covered with a thick blanket of hay. Signal lights were hung on each end, and an oil lamp provided light inside the car.

The first horsecar lines were also modest. St. Paul’s initial line was two and one-half miles long, and the Minneapolis line just two and one-tenth miles. Minneapolis line construction cost $6,000 per mile, and the completed tracks were made of five-inch-square wooden rails, or “stringers,” with wooden crossties and bent iron plates spiked onto them. The inferior quality track sometimes caused a car to derail, at which point passengers disembarked to help push it back onto the track. Passenger power was sometimes employed to assist a car up a steep hill as well.

The early streetcar barns housed both horses and cars and were staffed by a mechanic and a blacksmith. The first barn in St. Paul was located at Fourth and St. Peter Streets, and in Minneapolis at Third Avenue and Second Street.

The public could ride anywhere within the city limits of St. Paul or Minneapolis for just five cents. Passengers would drop a nickel into the fare box located in the front of the car before taking a seat. The first day’s revenue for the Minneapolis Street Railway Company totaled $21.50, collected from 430 passengers. By 1877, the company was running 18 cars and carrying an average of 17 hundred riders daily, with receipts totaling up to $100.

Maintaining the horsecar lines was expensive. The first cars cost $872 each. Six horses were needed for each car to keep them in operation for a full day. Horses cost $135 to $150 per head and were fed five times daily. Drivers (and later, conductors) worked 12 to 16-hour days in all weather for $35–$54 per month. With such high overhead, the lines were not cost-effective and employees sometimes waited several weeks to be paid.

While embraced by the commuting public, horse-drawn cars had serious drawbacks. The odor and health risks associated with horse pollution were a real concern. One horse can produce up to 50 pounds of manure daily. When dried, wind-blown manure dust contaminated the air. Health officials warned that the polluted air was responsible for the high occurrence of diarrhea, especially in children. Piles of manure attracted flies, and outbreaks of typhoid fever were a common problem for city residents. Rainy weather turned the dust into a sludge that made walking highly disagreeable.

Worse yet, horses were sometimes injured in the line of duty or succumbed to the burden of their work, dropping in their harnesses on the street. Unable to move the heavy carcasses, drivers would leave them where they fell, and a cart was eventually sent to collect them. The carcasses posed health risks and blocked traffic.

1883

Thomas Edison exhibited the first electric locomotive in the world.

The first electric railway line, the Chicago El, had begun operation in 1883.

1884

Thomas Lowry and his partners took over the St. Paul City Railway Company.

The first overhead electric streetcar line was installed in Kansas City.

1886

The Minneapolis Street Railway Company (MSR) and the St. Paul City Railway Company (SPCR) began to operate under a single group of owners when Minneapolis businessman Thomas Lowry and his associates gained control of both.

1889

Over 15 months, Minneapolis converted from steam to the electric streetcar, running first on December 24, 1889. Frank Sprague had figured out to electrify the cars in 1887.

Electric streetcar lines were introduced in Minneapolis in 1889

1890

Electric streetcar lines were introduced in St. Paul in 1890. By that time, Minneapolis was running a total of 218 horsecars with 1,018 horses and mules on over 66.7 miles of track. St. Paul had one 159 cars with 900 horses and mules covering 53.3 miles of track.

The Interurban electric streetcar line was completed between the loops of Minneapolis and St. Paul, running down University Ave. through the Midway.

1892

On January 2, 1892, the Minneapolis Street Railway and the St. Paul City Railway became wholly-owned subsidiaries of the Twin City Rapid Transit Company, generally known as Twin City Lines or TCRT. The new holding company had been incorporated in June 1891 as a New Jersey corporation.

By 1892 all lines had been converted to electric operation and horsecars had been phased out.

1893

Bicycles (velocipedes) became an overnight sensation and put up stiff competition for the roadways til the fad cooled in 1897.

1898

The Como-Harriet interurban line was opened on July 1, 1898.

1909

Thomas Lowry died and his son-in-law, Calvin Goodrich, Jr. became president of the TCRT until he died in 1915.

1914

The Dan Patch Electric Railway, started in 1907 by Col. M.W. “Will” Savage, came to the Park running north-south.

Eric Wickman inaugurated the beginning of the “omnibus” when he transported miners from Hibbing to the iron mine. This eventually led to the development of Greyhound Lines.

1921

An independent company ran a bus line in Minneapolis.

1922

TCRT carried 226 million passengers, an all-time high. It had nearly 530 miles of track and 1,021 streetcars. The carhouse or station at 2108-2130 E. Lake St. was at the center of a trainman’s day. It was a home away from home, a private club of sorts. If you were a motorman, it was where you reported for work to pull out your car. If you were a conductor, it was where you got your change supply or turned in your receipts at the end of the day. Or, it was a place to catch some sleep between a late-night run and an early pullout the next morning. The system was dismantled in 1954, and Lake Street Station was demolished and now houses the Hi-Lake Shopping Center.

After 1922, ridership began a gradual decline, due to the increase in automobiles.

1926

TCRT bought up all independent bus lines and all taxi companies. The city smelled monopoly and ordered the taxis sold later in the year.

THE MOTORETTES

Between July 1943 and November 1945, the TCRT hired 381 female streetcar drivers or “motorettes” to replace motormen who had gone to war. Read the whole story by Twin Cities mass transit expert Aaron Isaacs Here.

Three of the first motorettes report for work at Nicollet Station, Thirty-first Street and Nicollet Avenue, Minneapolis, 1943. Photo courtesy Hennepin County Library.

1947

The bus first came to Knollwood. TCRT added 50 new streetcars and 90 new buses.

1949

From the Minnesota Streetcar Museum website:

Late in 1949, New York City investor Charles Green gained control of TCRT. Determined to squeeze dividends from a company that traditionally reinvested its profits in system improvements, Green discontinued the rebuilding program, trimmed maintenance to a minimum, laid off hundreds of employees, relentlessly cut schedules, and announced a goal of complete conversion to buses by 1958. His heavy-handed policies so alienated the public that in 1951 he was ousted and control passed to his local partner Fred Ossanna. [It was rumored that Green made a $100,000 profit when he sold.] Mr. Ossanna introduced further economy measures and continued to reduce service as patronage dropped. A Los Angeles expert on conversion to buses, Barney Larrick, was hired and the system was completely converted by 1954.

Ossanna, rebuffed by local financiers, went straight to General Motors, hoping to buy 25 new diesel buses. Roger Keyes of GM (later to become Assistant Secretary of Defense) found conditions so promising that he was willing to extend credit to buy 525 new vehicles. USA Confidential posits that “Joe Massei, of Detroit’s Purple Gang, with a bundle of Mafia cash, was in on the deal.” Ossanna, Barney Larrick, and two of their associates were convicted on August 6, 1960 of defrauding the TCRT of company assets, including scrap metal and real estate, during the conversion.

In the 1950s Excelsior Blvd. was served by the Deephaven bus line.

1954

Conversion from streetcars to buses was officially declared completed on June 18, 1954, after 15 months, with a fleet of 525 buses replacing Minneapolis streetcars. Twenty cars went to Cleveland, 30 to Newark, and the rest of the more modern cars went to Mexico City, where they were used into the 1980s. Offers of jute bags from India, coffee from Brazil, and beef from Argentina were apparently turned down. (Minneapolis Star, June 22, 1954) The older, home-built cars were sold to private citizens for things like lake cottages, construction shacks, and camp mess halls. Those that could not be sold were burned. The photo below is of Ossanna receiving an insurance check from agent James Towley to cover the “loss” of the car Ossanna just gleefully burned. (Minneapolis Tribune, June 19, 1954) This classic photo enraged streetcar proponents. Ossanna was later convicted of mail fraud and sentenced to four years in prison. Barney Larrick, TCRT vice president was sentenced to two years. TCRT also filed a civil suit against Ossanna, seeking restitution for losses from assets (like scrap metal, copper) that were sold at below market prices for kickbacks. Those convicted pocketed over $1 million of TCRT assets in 1950 dollars. (Hennepin County Library)

1955

The City Council was alarmed at the reduction of bus trips on Excelsior Blvd. from 59 to 37.

1962

Twin City Rapid Transit Company changed its name in 1962 to Minnesota Enterprises Incorporated (MEI).

In the mid 1960s buses began to have numbers to define their routes. Before that they were simply known by the streets they used. St. Louis Park’s bus routes were:

- Route 12 went down Hennepin Ave., Lake Street, and Excelsior Blvd. between downtown Minneapolis, SLP, Hopkins, and Minnetonka.

- Route 14 went down Glenwood Ave. and Cedar Lake Road.

- Route 17 went down Nicollet Ave., 24th Street, Hennepin Ave., Lake Street, Minnetonka Blvd., and Texas Ave.

- Route 51 was added in the late ’60s to 1970. It went to and from downtown Minneapolis to Wayzata going through St. Louis Park on Highway 12 (now I-394).

1970

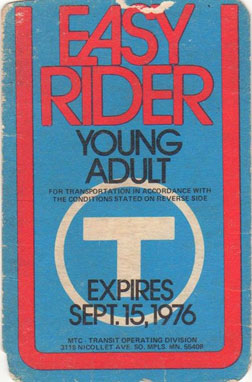

Of the 635 buses in use in the region, 480 were over 15 years old and about 6 percent were so old that they were banned from the City of Minneapolis. In 1970 MEI left the transit business with the takeover of its Twin City Lines subsidiary by the Twin Cities Area Metropolitan Transit Commission (MTC). The MTC was formed by the Minnesota Legislature and charged with maintaining and improving public mass transit in the Twin Cities area. The MTC spent $20 million on 465 new air-conditioned buses, installed 135 bus stop signs, and established a 24-hour information center.

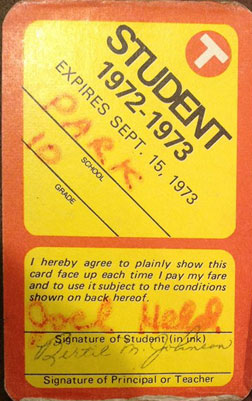

1973

Starting on July 16, 1973, St. Louis Park became the first Minneapolis suburb to have its own MTC minibus system, the St. Louis Park Crosstown. 19 buses (capacity 17 passengers) traversed a route between 44th Street and Wooddale on the south to Highway 12 and Louisiana, every half hour, Monday through Saturday. Principal stops were the library, schools, rec center, St. Louis Park Medical Center (now Park Nicollet), Methodist Hospital, Westwood Shopping Center, Shoppers’ City, and Miracle Mile. The fare was 25 cents for adults, 20 cents for students. The buses were dedicated at a ceremony at the Rec Center. The action was the result of a study by the Citizens Advisory Committee. By February 1974 the Echo reported that the route (36A and 36B) suffered from a lack of riders.

1974

In July the St. Louis Park minibus service was and replaced full-sized buses and extended to Southdale.

In August 1974 Route 36B, the “Ridgedale Hop ‘n’ Shop,” traveled from Southdale through St. Louis Park, to Pennsylvania and Highway 12. There were 10 stops along the way and the system ran at 30 minute intervals, although not on evenings or weekends. The fare was only 30 cents.

In November 1974 the MTC added routes 17H and 17J which were express buses from downtown Minneapolis to St. Louis Park. Route 17H went to Target (at Knollwood) and Route 17J went into Hopkins just south of Highway 7.

Route 67 was an express bus that went to and from downtown Minneapolis to St. Louis Park, Minnetonka, and Deephaven via Minnetonka Blvd., Highway 100, and Highway 12.

1970s and ’80s

The Richfield Bus Co. had a route that went from downtown Minneapolis to Minnetonka via Minnetonka Blvd.

The MTC added route 75 that went from downtown to the Park, Minnetonka, and Wayzata via Highway 12. Route 51 and 75 were combined into route 675.

1977

On February 2, 1977, the Sun announced a free bus service to the St. Louis Park Library, stopping at seven locations in the Park on the first and third Thursday of the month. Bus riders had an hour to browse the library.

Route 52P service from St. Louis Park to the University of Minnesota started in September 1977. It started at the Target Store at Knollwood and followed 36th Street, Texas Ave., Minnetonka Blvd., France Ave., Ewing Ave., Wirth Parkway, Highway 12, I-94, I-35W, to the East Bank. The bus ran to the U two times in the morning and returned twice in the afternoon. The fare was 40 cents to 36th and Texas, and 50 cents ending west of 36th and Texas. The University Commuter Service was a cooperative venture between the MTC and the U of M. Route 52P was later changed to 652.

A 1977 ad in the Sun read “Why Pay More Than $1.00* to ride from St. Louis Park to Downtown Mpls.? On the MTC.. when The Excelsior-Minneapolis Line offers the same service for only 50 cents. Service provided by Richfield Bus Company Charter Service Also!! The route started in Chanhassen and came through the Park via Minnetonka Blvd. The * after the $1.00 meant “fare plus property faxes levied to support this service.”

1980

In January 1980 a conference was held in Wayzata called “Light Rail Transit: A Solution for the Twin Cities?” This was in response to the announcement the previous year that Highway 12 was slated to be expanded into Interstate 394. Mayor Phyllis McQuaid was a believer in the light rail as an alternative to bigger and bigger highways, but the idea got no traction at the State legislature or U.S. Congress.

2004

Light rail transit began in the Twin Cities with the Hiawatha Line.

2012

See a virtual tour of the Light Rail Transit line planned to travel through St. Louis Park.

PRESIDENTS OF THE TWIN CITY RAPID TRANSIT COMPANY

Thomas Lowry: 1873-1909

Calvin Goodrich: 1909-1915

Horace Lowry: 1915-1931

Julian McGill: 1931-1936

D.J. Strouse: 1936-1949

Charles Green: 1949-1951

Emil B. Aslesen: 1951

Fred A. Ossanna: 1951-1957

Dr. David E. Ellison: 1957

PART II: THE COMO-HOPKINS STREETCAR LINE

Although this streetcar line is not in St. Louis Park, it is important to our story because it was the mode of transportation that made the development of the Brookside and Browndale neighborhoods in the Park possible. The line ran just south of the St. Louis Park/Edina border, approximately along what is now 44th Street. It was primarily a shuttle between Minneapolis and Lake Minnetonka, and the mode of transportation that working people in Brookside and Browndale would have traveled to their jobs in Minneapolis.

1878

On July 1, the Minneapolis, Lyndale, and Lake Calhoun Railroad was incorporated by several Minneapolis and Columbus, Ohio businessmen, including Colonel William C. McCrory, whose farm was called Lyndale. The Lyndale Railway Co. started to construct a single, three foot gauge line, starting at Nicollet Ave. and First Street (Bridge Square) to 34th Street at Lake Calhoun.

1879

The Lyndale Railway Company began service from Minneapolis to Lake Calhoun in May 1879. Trains were pulled by two steam engines, which were camouflaged to look like cars. The line was also known as “McCrory’s Motor Line,” after Colonel William C. McCrory, whose farm was called Lyndale.

1880

The Motor Line was extended to Lake Harriet in 1880.

The Motor Line stop on Brookside Ave. (which is apparently labeled Main Ave. on an 1898 map) was named Emma Abbott, and the area on both sides of 44th Street was known as Emma Abbott Park. Emma’s father, Seth Abbott, had purchased the 127 acre farm of Jehu and Belinda Rutledge and platted the land. He named it after his daughter, a singer and guitar player who toured the world. The land passed to Emma, but she died young, and the dream of Abbott Park was never realized.

1881

In February 1881, the Lyndale Railway Company, which ran the Motor Line, changed its name to the Minneapolis, Lyndale, and Minnetonka, reflecting its ultimate destination.

1882

The Motor Line was extended to Lake Minnetonka in July 1882.

1885

McCrory’s Motor Line suffered financial losses due to overly ambitious extensions, and fell into the hands of Charles A. Pillsbury and James J. Hill.

1887

McCrory’s Motor Line was sold to the Minneapolis Street Railway Company on April 1, 1887. The tracks from Lake Harriet to Lake Minnetonka were abandoned. The demise was said to be due to lack of business.

1898

The first part of the Como-Hopkins line, the Como-Harriet Interurban Line, was opened on July 1, 1898. It started at 34th Street, east of Lake Calhoun.

1905

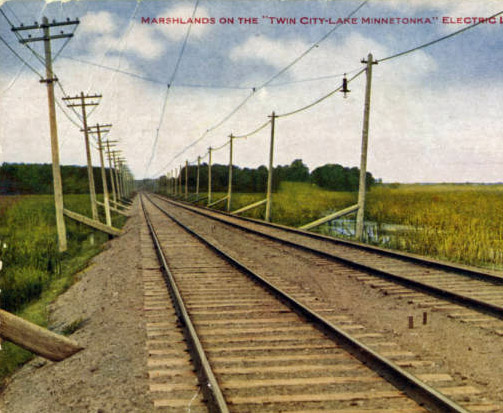

Twin City Lines bought up much of the old McCrory Motor Line route, started work in the spring, and inaugurated the electric Excelsior Line on September 30, 1905. The line went from Downtown to Morningside, Hopkins, and Excelsior. The right-of-way was widened. The 14 mile double track line was slightly different from that of the old Motor Line. It was standard gauge, and had local stops at Browndale, Mackey, and the Brookside Station, which was located at the corner of Motor Street [44th] and Main Street [Brookside]. An express ran to Minnetonka, and that train went so fast it was known as quite a wild ride. The line had some double decker cars, but they were decapitated because they weighed too much and were too hard on the infrastructure. Brookside Ave. crossed the tracks on an overpass that was removed in about 1956 or 1957. The tracks were laid on a private right-of-way, mostly following the route of the McCrory Line. Electric lights hung from the span wires.

The route of the Lake Minnetonka line was as follows:

Lake Harriet (31st and Irving)

what is now an alley on the north side of 44th and France

crossed France at an angle and moved to the south side of 44th

ran parallel to 44th to Brookside Ave.

across a marsh that featured cattails, ducks and shore birds

southern boundary of Meadowbrook Golf Course

through the woods along the southern edge of Blake Road, south of Blake School

crossed Washington Ave. (now highway 169)

took a viaduct over the Minneapolis and St. Louis Railroad and Milwaukee Road

Excelsior Blvd. between Hopkins and 494

south of Excelsior Blvd. (now housing)

continued west of Highway 101, Highway 7 to Excelsior.

1906

A second track was added to the Excelsior line was added.

The line to Excelsior was extended to include six “Streetcar Boats” that took passengers to the Big Island Park in Lake Minnetonka. The amusement park and hotel closed in August of 1911. The Excelsior line was known as the “white way” for the light poles every 400 feet. In 1924, Excelsior Amusement Park was built at the site of the waiting station for the streetcar boats. The streetcar boats were discontinued in July of 1926 and revived in 1996.

The Griswold Monorail Co. (same Griswolds as the Griswold Sign and Signal Co.) proposed building a monorail from Lake Minnetonka to Minneapolis.

1907

The Tonka Bay Hotel was purchased by the TCRT, and reopened in 1908. The building was designed by L.S. Buffington, and was built in 1879 as the Lake Park Hotel. It was four stories tall, had 200 rooms, and dining facilities for 500. The hotel closed in 1911, the same day as Big Island Park. The combination roller rink and dancehall would later be moved to the Excelsior Amusement Park.

1910

More than 60 passengers were showered with broken glass as an inbound Excelsior streetcar rear ended another in dense fog near the Brookside station on June 4. Victims were brought to Minneapolis hospitals by ambulance and by “automobiles and vehicles hastily summoned from nearby farm houses,” reported the Minneapolis Morning Tribune.

1932

In August, the Excelsior line was truncated and only ran to Hopkins instead of to Lake Minnetonka. It was at this point that it became known as the Como-Hopkins Line.

1951

In November 1951, the 3.3 mile stretch of track between Brookside Ave. and Hopkins was removed, and the line ended at 44th and Brookside.

1954

The last run of the Como-Hopkins line was on Conversion Day, June 18, 1954. The Minnesota Historical Society has a 78 rpm record of the next to last run of the line. The Village Council expressed an interest in a thoroughfare made of abandoned streetcar Right of Way from 44th and France to Hopkins. They would pay a share of the cost to buy the Right of Way from TCRT.

PART III: T.B. WALKER’S ST. LOUIS PARK STREETCAR LINE

On May 8, 1891, the Minneapolis Land and Investment Company (T.B. Walker, President) received permission from the St. Louis Park Village Council to build what was to become known as the St. Louis Park Streetcar Line. Click Here for the text of the ordinance and the acceptance by the Minneapolis Land and Investment Co.

Streetcars had a great deal to do with population trends in the young Village. In the days before automobiles, those who worked in town depended on the trains and streetcars to get to work. Walker’s streetcar made it possible for businesses to carry on along its tracks and fostered construction of homes in the area. In an interview in 1913, Walker said that another purpose of the streetcar was to encourage truck farmers in the Park to bring their produce to Minneapolis, thereby increasing the supply and lowering the cost of living for city dwellers. (Walker was first and foremost a Minneapolis booster.) Even after the advent of private cars, the streetcar was well used until it ended its run on August 28, 1938, to be replaced by buses.

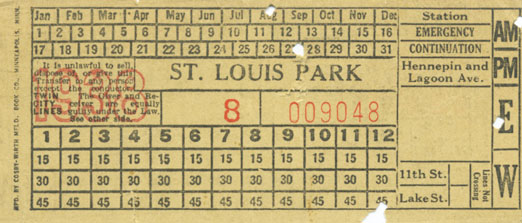

1892

The St. Louis Park line became operational in the spring [December] 1892 with 3-4 Pullman cars that were rented from the Minneapolis Street Railway Co. It started from 29th Street (Lagoon) and Hennepin, followed the Lake Calhoun shoreline, west via Minnetonka Blvd. and then southwest via Lake Street to Walker Street, where it turned around in a wye at what was known for decades as the “Waiting Station.” Fares were five cents, and a maximum speed was set at 25 miles per hour. It took 20 minutes to get downtown. Maps in Walker’s newspaper ads for the area indicated several extensions of the line that were planned but never built.

1897

Starting in August 1897, the “Black Mariah” of the St. Louis Park line extended into Hopkins. Once through the St. Louis Park business section, it continued on Lake Street to Monk (or Blake) Ave. Then south to Excelsior Avenue and west to the end, just east of 6th Avenue and Excelsior Avenue, where the Minneapolis and St. Louis tracks crossed Excelsior Ave. Cars were leased from the TCRT.

1902

The St. Louis Park and Hopkins Electric Line Car Barn at Brownlow was destroyed by fire from lightning on October 7, 1902. The carhouse and one car burned. The carhouse was rebuilt, but was damaged by the tornado of 1904 when the storm blew a car into the waiting station.

1906

TCRT bought Walker’s St. Louis Park line in November 1906 and made it a part of the Minneapolis and St. Paul Suburban Company. It is speculated that since both went to Hopkins and Hopkins was being served by the Como-Hopkins (then the Excelsior) line, the St. Louis Park segment to Hopkins was discontinued and the tracks were torn up in 1906-07.

1913

An article in the Journal dated November 2, 1913, indicated that when T.B. Walker’s St. Louis Park electric line was sold to TCRT in 1905/06, there was the expectation that there would be a 5 cent fare into the City, and when that happened, the Village would develop as a manufacturing suburb and residence district. The article also mentioned the Dan Patch line, then under construction, which would carry freight as well as passengers. “Until such time it was felt that it would be at least a drawback against bringing in settlements and improvements. Under these circumstances, the Park has lain dormant until the present time.”

1915

The Dan Patch Electric Line was built through St Louis Park. When the streetcar had to cross the Dan Patch, company rules required the streetcar to stop. The conductor would get off the back door, walk the length of the streetcar to the railroad crossing, flag the streetcar across the tracks, walk back to the rear door and re-board. That was rather time consuming. Passengers on the outbound car may have gotten off with the conductor and walked the last block to Brownlow because it was faster than staying on the streetcar.

Similarly, passengers on the inbound trip might have waited across the tracks to board rather than sit on the car for that whole process. It might have allowed them to walk to the streetcar a minute or two later than otherwise. (Aaron Isaacs)

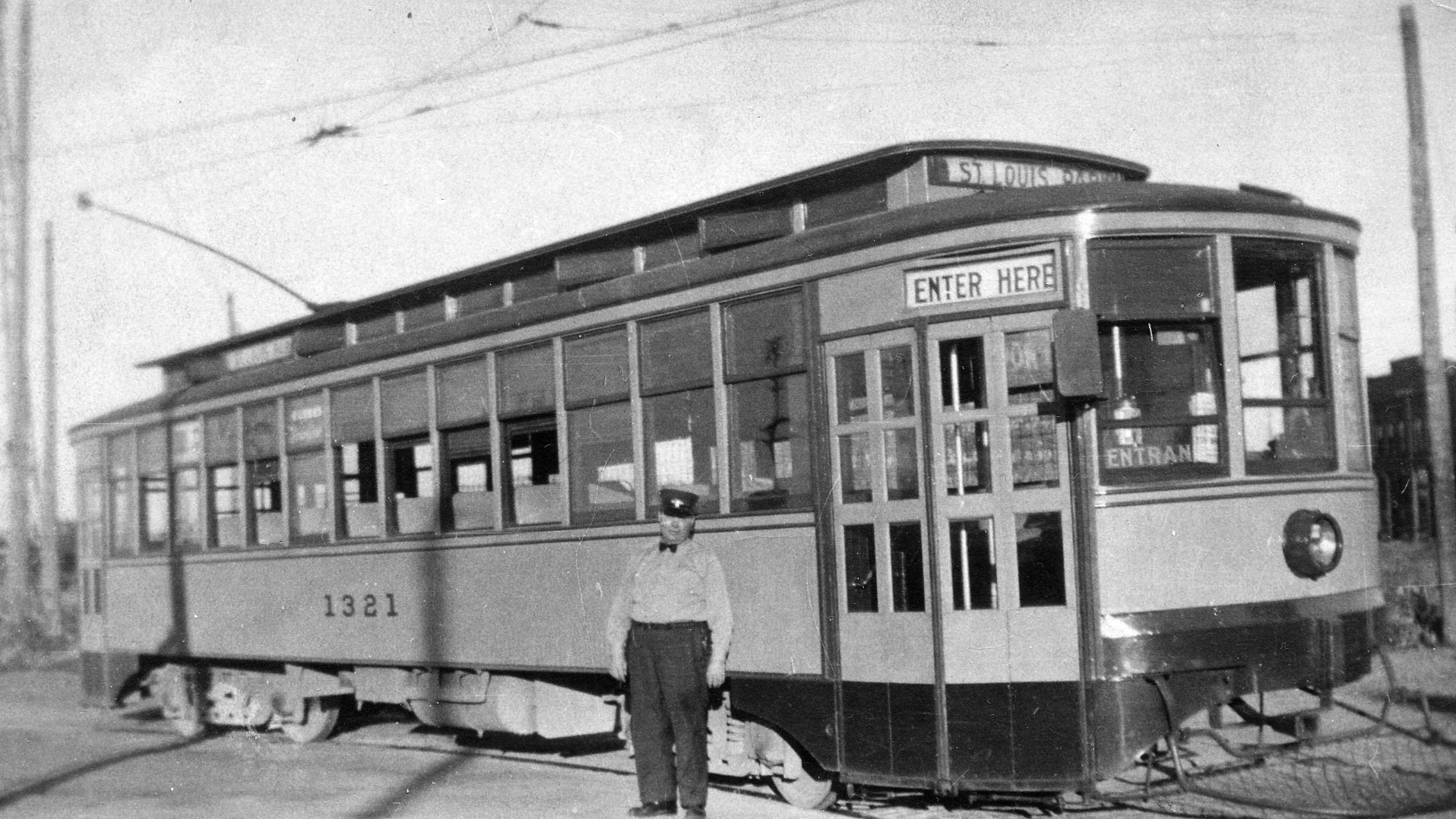

1916

The St. Louis Park streetcar line was temporarily severed to replace the bridge over the railroad tracks just west of Lake Calhoun in Minneapolis. During construction, a shuttle car served the outer portion of the line. Passengers had to get off, walk across the tracks and board another streetcar to continue into Minneapolis. Below is a photo of the shuttle car waiting at the west end of the bridge. (Aaron Isaacs)

1938

August 28, 1938, marked the last run of the St. Louis Park line. The Minneapolis Tribune reported that a huge crowd turned out at 12:40 am to say farewell. The process started in 1934, when the Village Council authorized the Council President to bargain with the Minneapolis and St. Paul Suburban Railway for bus service to replace streetcar service and to bargain for better service. Is it just a coincidence that the streetcar was taken out at about the same time Highways 7 and 100 were built? Many oldtimers later regretted the demise of the streetcar and expressed sentiment about the line, but news coverage at the time showed a different story. Residents “made real whoopie,” staged a “busline polka,” and 50 people rode the last streetcar into town, smiling and waving. The advent of buses appealed to riders because of their more flexible routes and more comfortable rides.

On November 22, 1954, the Village ordered the damaged waiting station at Walker and W. Lake Street removed.