ST. LOUIS PARK HISTORICAL SOCIETY August 2025

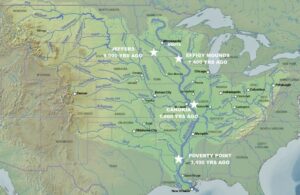

“The history of Minnesota starts here,” says the Jeffers Petroglyphs Historic Site, 150 miles southwest of today’s St. Louis Park, a 3-4 day walk. The site records and documents 9,000 years of occupancy by the Ioway, Otoe, Cheyenne, and Dakota people.

Up to 11,000 years ago, most of Minnesota was buried under a mile of glacial ice which melted and drained north to the Arctic, east to the Atlantic, and south to the Gulf of Mexico. Over millennia, the Mississippi River watershed became the travel and communications network for multiple native civilizations; its waters sustained all life.

In 1803, the land under future St. Louis Park was purchased from Napolean Bonaparte by President Thomas Jefferson. The land’s occupants were not consulted. In 1825, the U.S. Army planted Fort Snelling atop the Dakotas’ sacred place, Bdote, and in 1851 the Treaty of Traverses des Sioux formally transferred the land. The U.S. breeched its treaty obligations, which would ordinarily nullify the purchase, but armed force prevailed and the land we occupy today remains stolen.

The year 1855 was pivotal – the Public Lands Surveying System (PLSS) abruptly changed the culture from one where the land cannot be owned to one where the land must be owned. St. Louis Park was gridded and sold off into 40, 80, and 160-acre farms. As Ousamequin, a leader of the Wampanoag, explained over two hundred years earlier when European migrants began arriving on the east coast:

What is this you call property? It cannot be the earth, for the land is our mother, nourishing all her children, beasts, birds, fish and all men. The woods, the streams, everything on it belongs to everybody and is for the use of all. How can one man say it belongs only to him?

Post-glacial, St. Louis Park land became Oak Savanna and Wet Prairie; the oaky uplands managed by natives with fire over millennia to support wildlife; the wetlands drained or filled by settlers to make farmable or buildable plots. Except for the northern city edge, the land drained to Minnehaha Creek.

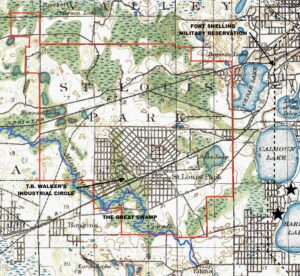

After 1855, when Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem The Song of Hiawatha became a worldwide sensation, (think Hamilton!), Minnehaha Falls became hugely famous, and tourists flocked to see it. What had been called “Brown’s Creek” since 1830 became mythic Minnehaha with its fictional trochaic tetrameter. Eventually, “Rice” Lake became Hiawatha; “Amelia” became Nokomis. According to a single map reference included in a 2016 City of Minneapolis study, the Dakotas’ creek-name might have been Wakpa Cistinna. That study also mapped native villages (starred) on the Fort Snelling military reservation. Following the Civil War, railroads forced their way through town, flat and straight from Minneapolis to points west.

In 1886, the accidental assembly of must-be-owned small farms incorporated as the Village of St. Louis Park. Minneapolis business leader Thomas Barlow Walker and his fellow land speculators almost immediately bought up the south half of the village and tried to develop industry and a town center around the two railroads – the Minneapolis & St. Louis and the Milwaukee Road. (James J. Hill’s Great Northern on the north side of town had no interest in providing local service.)

Walker’s group eventually failed, but the inertia of that industrial impulse led to abuse from the continual dumping of toxic industrial wastes into the Creek and its wetlands. The City and the Watershed District have cleaned things up over the last 50 years, developing housing, lighter industry, and open space. Returning Minnehaha Creek to a semblance of its meandering, wetland self is helping restore the spirit of the place.

The artificial political boundaries of St. Louis Park, Minnesota, provide local context but are irrelevant to understanding places where the land cannot be owned. Thinking in terms of watersheds is a useful beginning. We hope this “Land Statement” is also a useful beginning.

Today we have the power to instantaneously connect to communities around the world. New information is being added daily. It is incumbent on us all to continue the study of our origins. You could start here:

https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=46170

The Minnesota and Mississippi River Valleys have been home to the Dakota for hundreds of years, and the existence of our ancestors was sustained by their relationship with the earth and their surroundings. For generations, Dakota families fished from the rivers, gathered rice from area lakes and hunted game on the prairies and in river valley woodlands. Along the riverbanks, leaders of the Eastern Dakota, including Sakpe, Caske, Mazomani, Wambditanka, Huyapa, Tacanku, Waste, and Taoyateduta, established villages. From these home sites, the Eastern Dakota traveled for hunting, gathering, and meeting with other bands of Dakota. Our ancestors lived in harmony with the world around them, and Dakota culture flourished. – De Dakod Makoce Unkitawapi E E

The Minnehaha Creek Watershed: Where the land cannot be owned, the flow of water is the spirit of the place.

Creekside Park: A throwback to original lands, and a contemplative urban respite.