Much of the the initial information received about the Pest House came from Audrey Kuhne, a volunteer at the Service League of Hennepin County Medical Center, in 2000. The subject lay dormant for many years, when, in 2013, John Ryan found just the right person to ask more questions: Bob McCune, Records Coordinator for the City of Minneapolis (“City Archivist”), native Parkite and 1964 graduate of Park High. Bob and John and the St. Louis Park Historical Society are working to shed even more light on this fascinating subject.

OVERVIEW

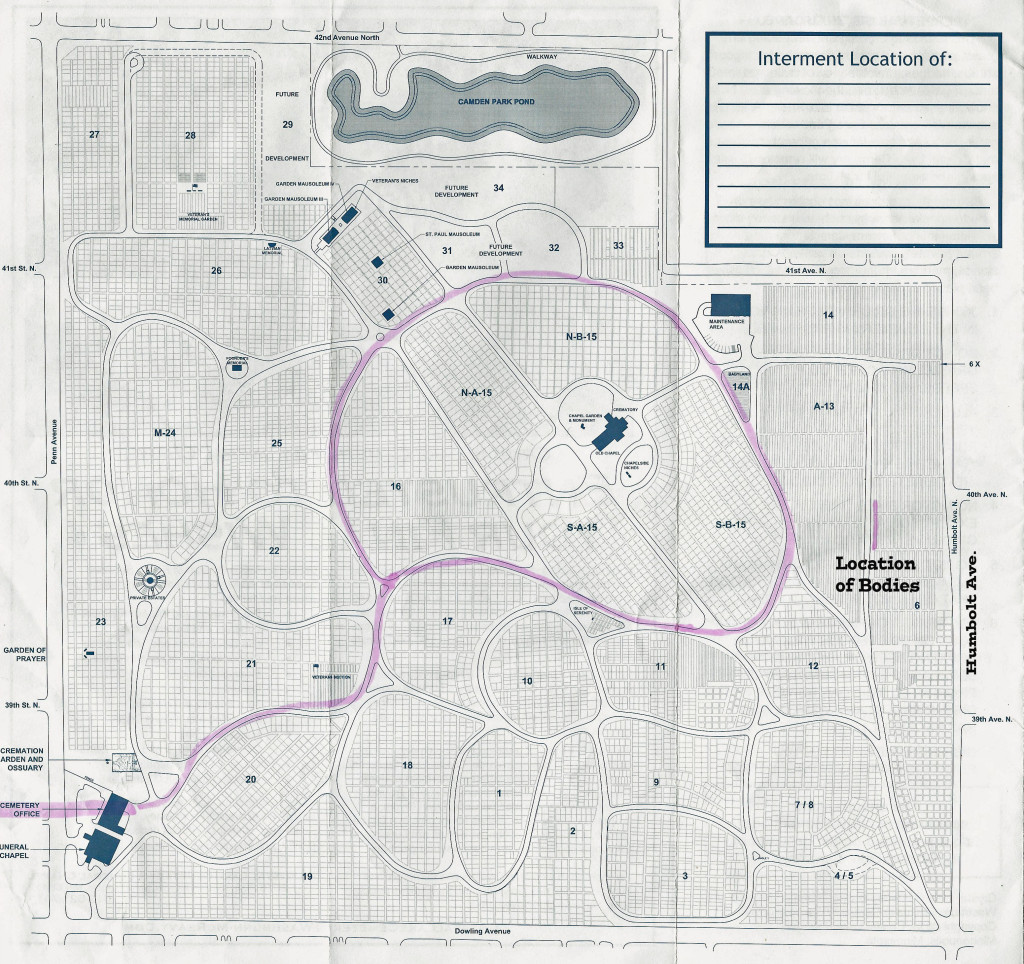

The Minneapolis Small Pox Quarantine Hospital (“The Pest House”), was situated on land in St. Louis Park that had been purchased by the City of Minneapolis. It was located between Kipling and Joppa, Minnetonka to the Milwaukee Road tracks. Highway 7, which was built in about 1934, bifurcates the tract now. The 1898 map below shows the area, labeled as “City of Mpls.” The horizontal line toward the top is Minnetonka Blvd. The right border is France Ave. The curvy line below denotes the railroad tracks.

Minneapolis sent its patients with smallpox and other communicable diseases to this outpost to either get well or die; those who succumbed were buried in the adjacent “Potter’s Field,” located on the northern part of the property.

Contrary to what was previously thought, John Ryan says that “Very few people from the Quarantine Hospital actually died and were buried there. I’d say maybe 100 out of the 3,000 that were buried there over the years. The city kept meticulous death records and there were many years where there were no deaths at the Quarantine Hospital at all. The cemetery’s official name was “The City Graveyard” and it was used to bury people from Minneapolis whose families could not afford to pay for burial – mostly immigrants, single people and infants. It was maintained by the superintendent of the Quarantine Hospital.”

THE ORIGINAL PEST HOUSE (MINNEAPOLIS)

1869

In January Minneapolis Health Officer Dr. Lindley alerted the Town Council about cases of smallpox and urged immunizations for “all citizens who have not yet been vaccinated.” The first smallpox vaccine was developed in 1798. In May Lindley advised the construction of a contagion hospital “at once” and a tract was purchased in North Minneapolis known as “Negro House and Land” or “Negro Hill.” Bob McCune has estimated that this location would have been just north of 26th Ave. No., which at the time was just north of the city limits. This is based on H.W.S. Cleveland’s description: “Following this avenue [Lyndale] two and one half miles north from Central Park, we come to the present site of the pest house, immediately in the rear of which rises a hill from which is obtained the finest view I have seen of the central portions of the city….” Patients were being admitted by the end of May 1869. Records seem to show that occupancy was relatively low.

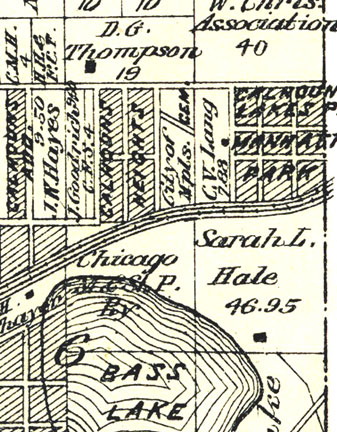

The land where the old Pest House was located became part of Farview Park, which is bounded by 29th Ave. No., 4th St. No., 26th St. No., and Lyndale Ave. The park “comprises an area of 20 82/100 acres, and occupies the highest point of land within the city limits, and commands a view of the entire city, as well as the course of the Mississippi river for miles. Its surface is diversified with lawns and groves, whose natural beauty will be augmented by the magic touch of landscape art.” A map of Farview Park is shown below. The old Pest House buildings were burned down in 1885.

1871

On March 9, 1871, the President of the Hennepin County Medical Society, Dr. A.E. Ames, wrote a letter telling doctors that no patients with contagious diseases may be admitted to the new Cottage Hospital (later called St. Barnabus) “as the city itself already has a pest-house outside the city limits.”

1882

The record suggests that part of this original Pest House grounds be set aside as a Potters Field, but there is no indication that this was actually done. An article in the St. Paul Daily Globe dated September 7, 1892, indicated that “The bodies were originally buried in the Tenth ward, but were removed to the quarantine hospital burying ground.” The original Pest House was in the Third Ward. It may be that bodies were moved to the St. Louis Park site from Layman’s Cemetery.

1883

John Ryan found this in the New Zealand Tablet of February 23, 1883 – amazing!

A PEST HOUSE

The pest house at Minneapolis, Minn., is at present over-crowded with small-pox patients, and a funeral invariably follows a few days after a patient is taken there, six members of one family having died within a short time. This wholesale slaughter has been going on for some time, and the matter is now being investigated. The keeper uses his best effort (so it seems) to spread the disease, by going into the streets of Minneapolis, and in fact, enjoys and unrestrained freedom in this matter. The patients are fed on the most unwholesome food and are nursed like a drove of hogs. Several prominent physicians are constantly violating the law by not sending patients to the pest house, considering it “murder in the first degree.” Father McGoldrick, the parish priest, the only Christian minister ho has visited the pest house, says: –

The condition of things there has been “horrible.” I would almost as soon have a friend of mine die outright as to be sent there. The condition of the people there has been almost too terrible for description, and simply from the criminal neglect of their fellow-creatures. People have a superstitious dread of the small-pox. The fear which seizes them seems to deprive them of the power of intelligent action. The health officers have done their part as well as they could, under the circumstances, and their greatest fault appears to have been in not keeping the public stirred up on this all-important subject, and only once before have they been pressed as they are now. So when the present epidemic broke out, they were entirely without proper means of handling it. True, they have done well in stamping out the epidemic, but the other duty to be performed lies in the caring for those already sick. The wretched hovel which has been used for them is utterly unfit for any such purpose. It is small, low, dirty, and ill ventilated. It contains three rooms in all – two for the patients and one for the attendants. The stench is dreadful. There were at one time eight patients in the lower room, and, in one case, two in a bed. Think of it! Eight people afflicted with this terrible disease placed together about as thick as they could be in one small, dirty, poorly-ventilated, ill-heated apartment. The condition of things could scarcely be much worse. At one time the water supply gave out, and the patients, in their desperation, were without water for three hours. In the room of the attendants, the bed which they occupied was placed right by the stove, where all the food of the patients was cooked. In almost every respect, the arrangements were filthy and unhealthy, and the attendants themselves do not seem to have been sufficiently skilled for their position.

Bob McCune says that “The hardship case referred to in the narrative is more than likely that of the Swedish immigrant family, the Johnsons, who entered the hospital together in 1872. The father and mother were afflicted with smallpox, but none of the children were ill. What became of the father is unclear, but the mother succumbed and the children of the family were adopted by concerned citizens out-state who had read about their plight in the Scandinavian paper. (Petition A1473).”

THE MOVE TO ST. LOUIS PARK

In April and May 1883 the Minneapolis council was eager for the North Minneapolis Pest House to be moved. On April 27 a petition was filed from James L. Monroe and others, and from Charles Hoag and others requesting that immediate action be taken for the removal of the pest house. The Council directed the committees on public grounds and buildings and health and hospitals to select and purchase a tract of land at or beyond the city limits for a site for a city hospital for contagious diseases.

In August the Board of Supervisors of the Poor advised the City Council that a ten acre lot be purchased by the city for a “potter’s field.” The petition was referred to the committee on Public Grounds and Buildings.

On September 12, 1883, the City of Minneapolis purchased 8.7 acres in St. Louis Park for a “quarantine station” from P.P. Swanson for $3,500. Charles Hanke and Joseph Hamilton of the Town of Minneapolis (to become St. Louis Park in 1886) protested the move to no avail.

The 1883 Report of the City of Minneapolis Comptroller shows payments for labor, bricks, hardware, lumber, stone, hardware, and 44 barrels of lime starting on January 3, 1883, but that may have been for the old facility, as it appears that the St. Louis Park site wasn’t started until 1885.

1885

The bid of $6,484 of Owens and Evans was chosen to construct the new Pest House on October 5 and construction commenced.

The Board of Supervisors of the Town of Minneapolis (the precursor to the Village of St. Louis Park, which was incorporated in November 1886) adopted the following resolution on November 2, 1885 and submitted it to the City of Minneapolis on November 4:

WHEREAS, It has been reported to this board of supervisors that the corporation of the city of Minneapolis is about to erect a pesthouse as a place of reception for persons affected with smallpox and other contagious diseases upon that portion of section six (6), township twenty-eight (28), range twenty-four (24), owned by said city, and being situated in a thickly settled portion of this town and adjacent to a much used public highway leading through the same;

AND WHEREAS, The erection of such pesthouse in said locality and its use for said contemplated purpose would greatly endanger the health and safety of the inhabitants of this town, be prejudicial to their interest and be a public nuisance;

AND WHEREAS, This board of supervisors, by virtue of the General Statutes of the State of Minnesota, constitute a board of health of the people of said town;

NOW THEREFORE, Be it resolved that this board of supervisors protest against the location and erection by the city of Minneapolis of such pesthouse in said proposed locality, for the reason that the same will, if there erected and used for the purpose of a place of reception for persons infected with contagious diseases, endanger the public health and safety of the inhabitants of this town, and be a nuisance to the public.

Resolved, That the chairman of this board be, and he hereby is, authorized and instructed to take, at the expense of this board, such legal steps as he may be advised are proper to prevent the erection of such pesthouse in said locality, or to prevent its use if erected, as a receptacle for persons infected with contagious disease, and to have the same abated as a public nuisance.

Resolved, That a copy of these resolutions be served upon the mayor, city attorney and president of the city council of said city of Minneapolis.

Joseph Hamilton, M. Ray, Supervisors

The petition was referred to the committee on public grounds and buildings, the committee on health and hospitals, and the city attorney. Unfortunately, the Town exercised no veto power over the actions of the City of Minneapolis and the petition was ignored.

1886

The Committee on Public Grounds and Buildings made the following report on January 6:

[We] respectfully report that [we] have erected a building 22 x 32 feet, 18 foot posts, with stone foundation and brick cellar, and which will accommodate about twenty patients. Have built a stable in connection with same large enough to keep one pair of horses, with room for ambulance, and have built out house, at a cost of sixteen hundred and twenty dollars ($1,620.00), and have turned the same over to the Committee on Health and Hospitals and the Health Officer.

Norman Campbell was selected to take charge of the hospital.

An article in the Dispatch from 1962 tells us that there was a sign at the entrance that read “If you come in, you’re here to stay.”

The Village of St. Louis Park was incorporated on November 19, 1886. The eastern boundary was established at France Ave., thus including the Pest House in the new Village.

DECADES OF COMPLAINTS

1887

Minneapolis Tribune, June 1, 1887:

The council committee on health and hospitals had a meeting yesterday with those citizens and representatives of the village of St. Louis Park who want the pest house moved. They thought anywhere but St. Louis Park would do for a pest house, and the committee rather agreed that the present site is not a fortunate one. They took no action, but will look over the ground.

It was apparently unclear whether the responsibility for the Pest House belonged to the Minneapolis Board of Health or the City Physician. On November 18, 1887, it was moved that the Board of Health be instructed “to cause the Pest House to be placed in a proper condition under the supervision of the Board of Health for the reception of patients at a cost not to exceed $500.” This resolution was referred to the Committee on Health and Hospitals with power to act. (Page 809 of City Council Proceedings)

On an undetermined date shortly afterwards, it was moved “That the city pesthouse be placed under the immediate charge of the City Physician, and he be instructed to attend all patients therein, and so all other contagious diseased city patients.” This resolution was referred to the Committee on Health and Hospitals. (Page 850 of City Council Proceedings)

1888

On February 17 the Standing Committee on Health and Hospitals recommended that the Minneapolis “Board of Health be provided with the proper means for placing the Quarantine Hospital and its grounds in a proper condition, and that in the future the Board of Heath may be held responsible for the proper care of patients placed there…” (Page 984 of City Council Proceedings) The Annual Report of the Board of Health for the year ending March 31, 1888, stated:

The Quarantine Hospital service has been re-organized, and the old building re-arranged and painted and new foundation wall built. A pavilion for contagious diseases, a wagon-shed, fuel house, ice house, chicken-house, piggery, and fumigatory chamber have also been added, and new beds and bedding procured. The ground has been surveyed and fenced, trees trimmed, and three and a half acres having been cleared of brush and now under cultivation. A horse and ambulance and a cow have been purchased, as well as wagons, sleds and implements for cultivation. A superintendent and matron are employed and twenty patients can be taken charge of at one hour’s notice and proper care given them.

On April 27, the Minneapolis Tribune reported on a visit to the Pest House by a number of Minneapolis aldermen. The facilities were described as follows:

The hospital is situated on a very pretty 8 1/2-acre plat of ground near the railroad and about a mile this side of St. Louis Park. The buildings consist of a two-story house, having rooms for the superintendent and his wife and other to be used by patients; a one-story neatly-constructed house, divided into two wards, for small pox patients and other with the more dangerous contagious diseases. Then there is a barn where a cow, horse and ambulance are housed. The smaller house was but recently completed, while the larger has been overhauled and repainted. Both are clean, well ventilated, and in every respect admirable for the purpose for which they are intended. The superintendent is a competent man for the place, being besides an excellent manager, a first-class man to care for the sick people, and his wife is a good nurse. The brush has been cut off of the ground and the houses are in the midst of a grove of trees. The larger portion of the land is being prepared for cultivation. ….

[Minneapolis Health Officer] Dr. Kilvington wants to get a fence put around the hospital grounds and signs to inform people of the nature of the place. Then with the whole place in such good condition and keeping, the city will have a model place where the sick can be cared for, and the objections urged by residents at St. Louis Park, who are tying to have the hospital taken away from that location, will be removed.

The 1962 Dispatch article said that there were five buildings in all, including the caretaker’s house. Unless there was an epidemic, about 25 patients were in residence at a time.

1891

On October 20, 1891, a Dr. Weston asked the Welfare Board whether to continue to treat cases at the hospital, and on November 3 that body voted to stop medical visits and pay no more bills for the station.

The Annual Report of the Department of Health for the Quarantine Hospital states:

During the past year 35 persons were sent to the Quarantine Hospital. Of this number 25 were suffering from contagious diseases and the 10 others were quarantined to prevent disseminating contagion. There were 9 cases of diphtheria, 4 cases of erysipelas, 5 cases of scarlet fever, 6 cases of measles and 1 case of septicaemia. There were 3 deaths, 1 from diphtheria, 1 from measles and 1 from erysipelas. All medical services were rendered by the medical inspectors and your commissioner, without any special remuneration.

Total expenditures for the Quarantine Hospital in 1891 were $2,029.40.

A barrel of gasoline on a freight train passing through Hopkins exploded, breaking every window at the Pest House, reported the Minneapolis Tribune on December 10.

1892

On January 19, 1892, the Minneapolis Superintendent of the Poor asked the City Council for permission to buy robes for the dead, but it is not clear if they were for the Pest House or the City Hospital deceased, or both.

The Minneapolis Tribune reported a cholera outbreak on September 7, as discussed at a meeting of the Minneapolis Board of Health. Once again a delegation from St. Louis Park (A.D. Mulford, William Regan, H.A. Turner, A.W. Swett and O.K. Earle) made a request that the Pest House be removed from the village limits.

They advance as arguments that two important lines of railways are located in close proximity to the hospital one one side, and that an electric line would soon be built on the other side; that there is much travel of all kinds in the vicinity, and that the grounds are adjacent to a rapidly growing community.

Howard Turner, the spokesman of the party, characterized the maintenance of the pest house in this suburb as an imposition, and said that it had already become a nuisance. The people objected strenuously to having cholera patients taken out there, and if the board would not willingly remove the hospital the village would compel it to do so, as they unquestionably had the law on their side…

..the St. Louis railroad in laying a new track in the rear of the grounds had encroached on the Potters field. So much earth had been dug away that in the event of a heavy rain the coffins in the graves would be exposed to view.

These complaints were given sympathy but as usual no action was taken.

The St. Paul Daily Globe reported the same meeting, and noted that to combat the threat of cholera the health commissioner was

authorized to adopt any precautionary method he may deem advisable. He will direct the disinfection of the refuse matter in all the depots, thus avoiding any danger from emigrants. At present the sawdust used in sweeping the union depot is saturated with a solution of corrosive sublimate, thereby insuring the disinfection of the entire building. A process for disinfecting all night soil and garbage will also be adopted.

The Globe characterized the St. Louis Park delegation’s concerns lightly: “The cholera has excited the people in St. Louis Park until they are ready to believe anything.” They did concede that “if a heavy rain should set in and wash away any of the dirt, the dead bodies will roll out of the graves and flop themselves about in a disheartening manner… The St. Louis Park citizens and officials are therefore fearful that these smallpox eaten bodies will interpose their grewsome bones upon the community, and infect the air with pestilential germs. It is conceded that the location of the pest house in St. Louis Park was wrong…”

Minneapolis Tribune, October 20, 1892:

… It is not generally known that the board of health has been preparing plans for a large detention hospital at the quarantine. An effort was made to keep it quiet, but it was not guarded very carefully, and the St. Louis Park people are up in arms against the scheme.

Plans are now being prepared in the office of the city engineer for a spur track from the St. Louis tracks up to the proposed new detention hospital. The grounds at the quarantine is a piece comprising between eight and nine acres, about 1,100 feet long and 330 feet wide, extending from [Minnetonka Blvd.] on the North to the St. Louis tracks on the South. It is proposed to locate the detention hospital in the northerly portion of the site…

The hospital as proposed is to be quite a large affair. It is contemplated to cost $7,000 or $8,000 and is to be fitted up with hot and cost water and all the accommodations of a first class hospital. The style designed is a double L, the connecting portion to be the offices, dispensary, etc., while the one wing intended for sick and the other for those only there for detention.

The plans of Dr. Kelley [head of the Minneapolis health department] are very good, so everybody admits, and there could be no valid objection in their being adopted and executed if the land was only inside of the city limits. There is the rub.

[Joseph] Hamilton, president of the village council of St. Louis Park, talks of arresting any person who brings a person afflicted with contagious disease into the village. He has had several consultations with his townspeople and H.J. Turner, representing the Par, has laid the matter before Dr. Kelley…

In a classic show of hindsight, on December 5, 1892, the Village Council passed an ordinance prohibiting “the erection or maintenance of hospitals or pesthouses within St. Louis Park for the treatment, harboring, or care of persons sick from infectious or contagious diseases and prohibiting the sending, bringing or coming into [SLP] of persons so afflicted.” In reporting the ordinance in an article called “Cast Out the Pest,” the Minneapolis Tribune revealed that “a plan was on foot to take that part of St. Louis Park into the city limits during the next session of the legislature, but this cannot be done without the consent of the people of St. Louis Park.” Meanwhile, Alderman Gray rejected the protestations of St. Louis Park. “We were there first, and if the village did not want the quarantine within their limits they could have left it out when they incorporated.” Perhaps a good point?

The December 8, 1892, St. Paul Globe clarified that:

The old hospital will be torn down and a new and larger one erected. Then the detention hospital.. will be built, also a cholera hospital, a crematory, a mammoth cess pool and an antiseptic building. These together with the superintendent’s building, will bring the number of city buildings on the land where now the measly quarantine hospital stands up to seen. the work on the new quarantine hospital will begin within ten days, and everything will be in readiness for cholera when spring and warm weather comes. The spur track from the main line of the St. Louis road will be built as previously arranged, so that all cars containing patients ill from infections diseases can be switched directly up to the building.

1893

On January 31, 1893, Minneapolis Mayor Eustis submitted a resolution to the Welfare Board that it should be the duty of the City Physician to attend to patients at the Pest House at city expense, in opposition to the request of Dr. Weston in 1890 to discontinue such visits.

In March St. Louis Park Boarding house proprietor and “wet” candidate for Village Council President Engelbert Kommers included in his platform the removal of the Pest House, and said that he would be in favor of burning it down if he couldn’t remove it otherwise.” (Minneapolis Tribune, March 4, 1893) He was not elected.

In April Minneapolis apparently put forth plans to erect a cholera hospital at the quarantine site, bringing on the wrath of not only the populace of St. Louis Park but of T. B. Walker himself. To be expected, his objections were in terms of the effect on further development of the suburb, which was his primary concern and purpose in creating it.

The quarantine hospital now there should be removed, and if the city of Minneapolis is taking steps to put in a cholera hospital it is an additional outrage on that village. It is particularly so, because the building up of St. Louis Park is for the benefit of Minneapolis and the men interested are doing the work there for the purpose of building up Minneapolis… This hospital stands in the way of Minneapolis improvement to the westward and of the extension of St. Louis Park to meet the building from Minneapolis.

The Board of Health discussed “the kick of the St. Louis Park people against the retention of the quarantine hospital in their midst. The board had no other place to put it, however, and it was decided to leave it in St. Louis Park.

In May the board of health of St. Louis Park directed Superintendent Boyer of the hospital to make a report of all deaths at the hospital and all cases of contagious diseases brought there. He was told that if he did not comply he would be arrested for violation of the health laws of the village. In response, Alderman Brazio denied that the hospital was a menace to public health.

I know from personal knowledge that is not the people of St. Louis Park (who, by the way, live a mile and a half away from the hospital), who are behind this movement to force the hospital away. I do not care now to say who they are, but there are other reasons than those given to the public that prompts this crusade. The movement is confined to a few individuals.

The village is playing the part of an ingrate. The city of Minneapolis has at a great expense graded West Lake St. [Minnetonka Blvd.] in order that its residents might have a good road to the city. It is evident that they are more greatly benefited than the citizens of Minneapolis by the improvement… If the village insists in driving out the quarantine hospital, we could retaliate in a manner that would not be at all pleasant.

In May Dr. Weston resigned and was replaced by Dr. Ricker as City Physician. The Welfare Board asked for a legal opinion about burying bodies on Pest House grounds.

The barbs continued to fly. Prominent Parkite O.K. Earle was quoted in the May 28 Minneapolis Tribune as saying “The way the hospital has been run is a disgrace to the management.” To that Superintendent Boyer replied that he will “mop the earth” with Mr. Earle and that the quarantine hospital is better conduced than any in the city.

On June 6, “after repeated delays, a few bluffs and much waste of wind,” ended up in an arrest when Superintendent Boyer was served with a warrant to appear before the village magistrate for violating Park’s health ordinance. He was accused of bringing a scarlet fever patient, one Charles M. McCann, into the village. Boyer had been hoping to be arrested for days but it took time to find a properly diseased patient. Lo and Behold, he was adjudicated before Justice of the Peace Charles Hamilton, son of village council president Joseph Hamilton. But the city attorney presented a state law that “directs the health officer to select a place for quarantining yellow fever, cholera, small pox or other contagious diseases at any point, but not to exceed three miles from the city limits.” The case was appealed to the district court and the judge found for the city of Minneapolis in terms of its right to maintain the Pest House. However, Boyer turned around and pleaded guilty to burying a pauper without a St. Louis Park permit, as a test case.

To Dr. E.S. Kelley, Commissioner of Health:

I have the honor to submit a report of the work at the Quarantine Hospital during the year 1893:

Total number of patients admitted, thirty-six; total number of patients detained, having been exposed to contagious diseases, four; total number of deaths, one; number of ambulance calls, forty; number of patients returned by ambulance, six hundred; number of bodies received for burial, one hundred twenty-two (adults fifty-eight and minors sixty-four); bodies removed, five.

William Boyer, Sup’t. Hospital

A complete inventory, from soup ladles to cuspidors, was also included.

Also in 1893:

Report of Cases at Quarantine Hospital

From April 1, 1893, to October 1, 1893 – Attended by Quarantine Physician, A.K. Norton, M.D., Medical Inspector.

To E.S. Kelley, M.D., Commissioner of Health:

In April I was appointed by the Department of Health as Quarantine Physician, with care of all patients at the Quarantine Hospital. I have had six (6) cases of Erysipelas, four (4) cases of Scarlet Fever and two (2) cases of Diphtheria, requiring fifty-seven (57) visits. There occurred but one death, that of malignant Phlegmonous Erysipelas. Since the purchase of the new city hospital, all contagious diseases are cared for there, except Small Pox and Cholera.

1894

On February 13, 1894, the Minneapolis City Attorney asked the Welfare Board to pay a $10 judgment against Pest House Administrator William Boyer for burying a pauper in the cemetery without permission from St. Louis Park. The bill was ordered to be paid, but only $8 of it.

1895

In January John J. Baston, State Legislator from St. Louis Park, introduced a bill that would have restricted quarantine hospitals to their respective city limits, but to no avail. Part of the reason is that the bill would have affected too many cities; the St. Paul quarantine hospital was just over the city line and the same was true for Duluth. The bill was passed in the house but thanks to heavy lobbying by Minneapolis it was permanently tabled. The February 4 Tribune cited this ulterior motive:

Besides all this talk about the objection to the present quarantine hospital is said to have an origin entirely foreign from the surface facts. The Minneapolis quarantine has an excellent railroad location – a location particularly desirable for a large elevator, and it is the talk that it is for the purpose of getting the site cheap that the opposition to the Minneapolis quarantine has been revived.

1896

The Minneapolis Welfare Board secretary was authorized to purchase a book to record burials at the cemetery. The condition of the fence enclosing the graveyard was inspected and a new iron fence was ordered and built. Bids and plans for a receiving vault were solicited.

In November the Minneapolis Tribune published a report charging that paupers were being buried before family members could be notified, with the result that the bodies had to be exhumed. Minneapolis Health Commissioner Avery denied the charge, but said “In the summer time it is impossible to keep the bodies unless they are called for immediately. I don’t understand why they are buried at this season of the year if there is a chance of their identity being revealed, as there are receiving vaults at the station in which the bodies can be kept.”

Report of Quarantine Hospital in City of Minneapolis Annual Report:

To H. N. Avery, M.D., Commissioner of Health:

I have the honor to submit a report of the work done at the Quarantine Hospital during the year 1896.

Number of persons sent to the hospital during the fumigation of their homes, seven; number of ambulance calls, seventy-one; number of miles traveled with ambulance, eight hundred and sixty five.

Some much needed improvements have been made on the place during the year; the buildings have been painted, the old dead trees have been removed and ground cleared up. The Board of Corrections and Charities have erected a brick receiving vault for the reception of dead bodies, and have put a new fence around the city graveyard.

Respectfully submitted,

William Boyer, Supt. Hospital

A full inventory was also provided.

1897

A smallpox epidemic that would last several years started in Florida and moved north, resulting in 25,000 cases and 195 deaths by 1904. The disease was spread by railroad porters, travelers, and switchboard operators. People often denied they had smallpox, or thought they contracted it from Spanish American War soldiers. A more likely source was Cuban refugees. Names for the disease were the Cuban Itch, the Manila Itch, the Philippino Itch, or yaws. It peaked in Minnesota in early 1899.

1899

Can’t make this up: July 7, Minneapolis Tribune:

A NICE PLACE TO VISIT

Aldermen Visit the Quarantine Hospital, and Now Some of Them Want to Have Smallpox.

A banquet fit for a king was served to the aldermen and physicians who visited the quarantine hospital yesterday. Supt. King acted as host, and Mrs. King presided as hostess.

After the luxurious feast, and while the dark Havanas were distilling a seductive fragrance, the committee strolled across the grassy plat that separates the superintendent’s home from the hospital. They found the wards of the long, one story building, veritable bowers of luxury and delight. Instead of a place to be shunned and avoided, the visitors thought it would pay one to court the smallpox or scarlet fever for the privilege of spending a few weeks at the attractive resort.

The newly painted walls, the light, airy rooms, the clean white beds, the smooth, hard floor, the beautiful grounds, the fine old shade trees – everything about the place was delightful.

“I wish I had the smallpox,” exclaimed one of the committee, as he exhaled a cloud of blue smoke, “just for the privilege of coming out here and spending a few weeks. It is one of the finest places I ever visited.”

The committee found the long building divided into three wards, with ample room for the the accommodation of 25 patients. The wards are not connected with each other, and can therefore be used in caring for patients suffering with as many different diseases as there are wards. Each large room is entered only from the open air, and there is no danger of germs being carried from one to the other, if reasonable care is used.

Adjoining each ward are sleeping apartments for the nurses.

The committee readily saw, when their attention was called to the matter, that a number of repairs and improvements were needed about the premises. The roof demanded a little attention. The foundation, which was originally intended to be temporary, must be replaced by a more permanent stone super-structure, and a new fence is required.

1902

Minneapolis Tribune, January 4:

GERMS IN THE SEATS

Eighth Warders Say They Are Jostled in Cars by Smallpox Microbes

ON PATIENTS FROM PEST HOUSE

They Want Vehicle Provided for Those Discharged From the Institution

The manner of discharging smallpox patients from the pesthouse is receiving the protest of residents of the Eighth ward, particularly those who patronize the St. Louis Park electric line. The complainants say that patients leave the hospital and go directly to the car line, boarding the first car that comes and transferring from that to other cars of the city lines.

They believe there is great danger of infection from this source and cite the case of a man who, discovering that he had been seated next to a discharged smallpox patient in the car, became frightened, and was shortly thereafter taken down with the disease. …

The only remedy they suggest is that the health department provide for the transportation to the city in an open vehicle, of discharged patients. …

Numerous casual indignation meetings have been held at street corners and in the cars.

Incidentally, a protest has arisen against the scant manner in which some of the discharged patients are clad. In several instances persons have been seen just released from the hospital, stand shivering in the cod without overcoats, while waiting for the car.

Ben Welter of the StarTribune posted this incredible story on his blog on October 30, 2012: From the Minneapolis Tribune, February 14, 1902:

CAKE WALK IN THE PEST HOUSE

Merry Social Function Given by Pitted Smallpox Patients.

Gus R. Scott and Lady Win the Prize After a Most Diverting Contest.

Those who have passed through the terrors of an old-fashioned smallpox epidemic and remember the terror that accompanied the very name of the pest house, will wonder aghast at a social function that was held Wednesday night at the pest house at St. Louis Park in one of the vacant ward rooms.

According to the report, life is a continuous round of pleasure at the public institution referred to. There are afternoon card parties, evening whist tournaments, debating tilts, spelling bees, and not a day passes that there is not some jovial amusement that drives away dull care, and many a friendship is made at the pest house that in future may be more productive of happiness than those at the seashore hotels.

But the function that capped the climax occurred Wednesday night, when there was an elaborate cake walk. A collection was taken up among the patients and a $10 cake was ordered down town, and was sent out to the house. In the evening the people gathered in a vacant ward room and there selected five judges, with John A. Burton as chairman.

There were 20 couples paired off to walk in the cake walk, the music being furnished by Charles Cabona’s Pest House orchestra.

It was a glorious occasion, and a great success. The match was close, but the judges finally awarded the cake to Gus. R. Scott and “lady,” who had carried off the honors.

Then the cake was cut and eaten to the fumes of the wassail bowl, and the music of merry quip and jest.

Think of that in connection with the pest house of ancient days.

1903

Pest House inmate James Judge escaped from the hospital on April 29 while the attendants slept, reported the Minneapolis Journal. He had wandered around most of the night in a snow storm and finally found refuge in a shed. He was found the next morning “cowering stark naked on a porch in the rear of a residence.” He was also covered in blood. When the resident of the house called the hospital, the attendant insisted that nobody was missing. The mixup was eventually resolved and Judge was returned to the hospital. Minneapolis Health Commissioner Dr. Pearl M. Hall immediately fired Superintendant Oscar Berger and named Sanitary Inspector Albert J. Lunt as his successor. Lunt said that an orderly was supposed to be on watch and that Judge had one of the worst cases of smallpox they had seen, “the disease having reached the confluent stage.” Judge later died.

In June Commissioner Hall was indicted by the grand jury, charged with neglect of patients at the Pest House. Superintendent Oscar Berger and his wife, Matron Gracie Berger, testified that they were compelled to do all the work at the hospital, and when they asked Dr. Hall for assistance they were refused. Sick patients were left without medical attention as it was rare that the doctor came to the hospital. The matter had been brought to the attention to the city health committee but the aldermen swept it under the rug. The indictment forced them to conduct an investigation.

In December Dr. Hall was hit was a $5,000 damage suit by James Judge’s mother. Other patients testified that there was no nurse on duty. Another witness was A.H. Wood, a night watchman at a grain elevator near the hospital, who came across a “bare-footed, bare-headed man clad only in a night dress. A severe north wind was blowing at the time, drifting the snow. Witness noticed that the man’s face was broken out..” Matron Gracie Berger testified that when she was hired in May 1902 she was told that she was expected to look after the part of the property occupied by her and her husband but ended up working from 5 in the morning until 12 at night. A nurse had left in July 1902 but was not replaced until April 1903.

Also in 1903, the roof of the servants’ house was leaking badly and new shingles were ordered in June. Superintendent Lunt stated that we would “hereafter charge $2 for adults and $1 for children pauper burials.” In August the increase was granted from $1 and $.50 previously charged.

1904

The hospital’s pump house burned down in 1904.

1905

A man broke out of a quarantine hospital in Iowa and joined a grading camp for the new Excelsior electric line. He was taken to Hopkins, where Dr. James Blake diagnosed him and sent him to the Pest House in St. Louis Park. The camp was thoroughly fumigated., but the crew fled in panic.

1906

Minneapolis Journal, January 22, 1906:

ST. LOUIS PARK HAS A SMALLPOX SCARE

Smallpox is giving the pupils and teachers of the St. Louis Park school a two-days’ vacation. A mild case has been discovered in a house nearby and as the children of the infected family have been about the school, it was thought best to give the building a thoro fumigation and it has been closed for this purpose.

The park is threatened with a smallpox scare as members of the afflicted family have been going about the community and it is reported that one girl, actually suffering with the dread disease, has been at large. The case is a very mild one, and, until a few days ago, did not seem to require the attendance of a physician. As soon as a doctor was called he discovered the nature of the disease and placed the family in quarantine.

Minneapolis Journal, January 28, 1906:

IN QUARANTINE WITH NURSE FOR COMPANION

Only Two Smallpox Patients in the City Aren’t Complaining

Martin Skordrud and William Le Clair are favored guests at the quarantine hospital at St. Louis Park. Messrs. Skordrud and Le Clair have the distinction of being the only smallpox patients in the city, and, strange to say, they are glad of it.

Their only companion at the quarantine hospital is Miss Anna Hollenbeck, a nurse. She has never had smallpox, but two years ago, when Health Commissioner P.M. Hall was unable to secure a nurse for the forty smallpox patients at the quarantine station, Miss Hollenbeck freely volunteered to take charge of the work. It was predicted that she would contract the disease, but she surprised all the authorities by going thru the ordeal unscathed, and she has been there ever since, as immune to the dread disease as if he had survived a serious attack.

Messrs. Skordrud and Le Clair are having a most enjoyable time of it. They read most of the time, and when they become weary of reading they engage in a game of cards or pay a social call on their nurse.

1907

From the Minneapolis Journal, November 1, 1907:

Officials Fight Smallpox. – There are seven cases of smallpox at the quarantine hospital, and it is believed that more are coming. The number is not large, but it is increasing, and the health officials are wondering whether the outbreak will assume serious proportions Minneapolis has been comparatively free from smallpox for about three years.

Local health officers were urged to stop the practice of quarantine and simply post a sign on the door of a house with an infected person. The rationale was that people could no longer count on quarantine to keep them safe and get them to get vaccinated.

1909

Mrs. Charles Hewes, chambermaid at the Roosevelt Hotel at 25 Sixth Street South in Minneapolis took sick and was eventually diagnosed with smallpox in October. When her condition was discovered, doctors and policemen came to the hotel and the clerk roused the guests so that those who had not been vaccinated could “submit to the operation.” “There was no opposition offered the doctors and none of the guests seemed to be afraid of the disease. In fact some of them joked about the matter. About ten men were vaccinated. Mrs. Hewes was taken to what was called the “detention hospital” in St. Louis Park.

1911

A new furnace was requested.

1912

October 6, Minneapolis Tribune:

Sacrifices to the Cause of Health, Guinea Pigs Don’t Seem to Mind It

Guinea Pigs Enjoy Life

But When They Get Portly They Are Offered Up as Smallpox Sacrifices

Hundreds of guinea pigs are living in clover at the City Quarantine hospital, Manhattan park, at the city limits, and are getting fat and comfortable with continued care and a diet of clover eaves.

But their revels are short. When they get portly, health and good-natured they are going to be taken into the laboratory of the hospital and put on a diet of smallpox germs and on the dissecting table of the laboratory they will give themselves up to scientific investigation.

Nearly 200 guinea pigs have been in the laboratory since last January. Mr. Smith, superintendent of the hospital, says that guinea pigs are the easiest animals for use in the laboratory because they have the least intellect and can be raised easier than any others.

According to Mr. Smith, the pigs do not know enough to burrow and so can easily be kept in a pen out of doors during the summer. All they do is squeal and eat and they do not have any intelligence.

The pigs live in the basement of the superintendents house during the winter and are fed on stock beets which Mr. Smith raises in his truck garden for that purpose.

Patients at the quarantine hospital have a strong attachment for the guinea pigs who are eventually going to die for the cause. The pigs are the pets of the institution and during their short lifetime have everything any guinea pig could desire.

1913

The Annual Report of the Minneapolis Board of Health shows that the Superintendent of the Quarantine Hospital was Charles Schmidt, and his wife was the Housekeeper/Matron. He made $50, she made $45, a nurse made $35, the ambulance driver made $40, the laundress made $25, and two maids each made $20. Burials were reimbursed to five companies, what looks like four individuals, and to Superintendent Schmidt.

1914

On January 1, the supervision of the “quarantine hospital for smallpox” was transferred from the Minneapolis Health Department to the City Physician after a vote of the Minneapolis City Council.

At their meeting on October 26, 1914, the St. Louis Park Commercial Club agreed to work with the Village Council to remove the Pest House. Adjoining property owners were Mr. McKenzie and Mr. Curtis.

December 30, 1914: An article from the Minneapolis Journal reported:

St. Louis Park citizens are demanding that Minneapolis discontinue its smallpox quarantine hospital and adjoining pauper burial place in that village on the ground that the hospital is a health menace, as homes are being built near it, and that the burial place is not properly conducted and licensed as required by law. The move follows proposals by Dr. C.E. Dutton, city health commissioner, that provision be made for smallpox patients in the new contagious building at the city hospital [the West Wing, finished in 1912] and that a crematory be built for the disposal of bodies of paupers. Burt H. Carpenter is chairman of the St. Louis Park Commercial Club committee appointed to protest to the city council. That bodies have been buried two and three feet deep and in long trenches and left uncovered in the potter’s field in other winters and other charges were made by committeemen…

A longer article on the same day in the Minneapolis Morning Tribune had more graphic details:

Later the practice was begun of burying the pauper dead in the same plat of ground without consulting the village officials. Several hundred bodies have been buried there, it is said, without so much as a notification to the village health department. For the last two or three years it has been the practice, according to the commercial club members, for long trenches to be dug for the graves. When a body is buried it is incased in a rough pine box and paced in the trench beside the coffin of the last pauper. In Summer the coffins are well covered with earth, but in Winter the coffins near the unused end of the trench are covered very lightly. Sometimes, after a windy day, the surface covering of earth is blown away, according to the protestors, and as many as two or three coffins lying near the end of the trench are exposed.

The contagious hospital is located near the street car line. Often residents of the village say, convalescent patients discharged from the place take the cars while their faces are still scarred from disease and their clothing is heavy with the odor of formaldehyde. While not perhaps in a condition to spread disease the appearance of much patients, the villagers say, is sufficient to ensue a near panic.

1915

The Minneapolis City Council Committee on Health and Hospitals ordered the acting Health Commissioner to ensure that every patient discharged from the Quarantine Hospital be inspected by a doctor first. The committee also ordered repairs be made at the hospital and instructed Edwin Alfred, Superintendent to get an estimate for wiring the buildings for electric light, as they were still using kerosene lamps. The Committee also requested that an automobile ambulance be purchased for the purpose of transporting patients to the quarantine hospital, approved by the City Council not to exceed $2,500.

On April 22 the St. Louis Park Village Council requested the State Board of Health to confer with the Health Board of Minneapolis relative to the burial of paupers in the Quarantine Hospital grounds to the end that same be discontinued.

On June 6 Thomas Smith was found wandering near his home at 44th and Wentworth. An ambulance was called but policemen were dispatched by mistake. When Smith’s ailment was found to be an advanced case of smallpox, the cops said “Suffering Cats!” when told they had to get vaccinations.

“Potter’s Field Fight Won by St. Louis Park” read the headline on July 8. The Board of Charities and Corrections agreed informally to take immediate steps to remove the hospital and discontinue as soon as possible burying the city’s poor on the grounds. They discussed building their own crematorium at Hopewell Hospital, which they estimated would cost about $6,000. They estimated they could get about $5,000 for the Pest House property.

An article dated September 29, 1915, indicated that the Board of Charities and Corrections was under the impression that there were only about 400 bodies to move out of St. Louis Park, when there turned out to be about 3,000. (Minneapolis Morning Tribune) In November the Board filed a petition regarding the maintenance of the quarantine hospital.

The Minneapolis Health Department transferred the Pest House to the Board of Charities and Correction. The buildings and land were to be sold and the proceeds used to prepare a new wing at the City Hospital for smallpox patients. The Board was to take over the management of the Quarantine Hospital on January 1. Fiscal sleight of hand left no allowance for the maintenance of the Quarantine Hospital and no funds to finish the addition to the City Hospital by the first of the year. (Minneapolis Morning Tribune, October 7, 1915)

In November the Minneapolis Board of Charities and Corrections filed a petition regarding the purchase of two acres of cemetery grounds from the Crystal Lake Cemetery Association for the burial of indigent persons. Minneapolis Morning Tribune, November 24, 1915:

Potter’s field will pass out of existence in Minneapolis just as soon as the Board of Charities and Correction can complete arrangements for the purchase of two acres of land inside Crystal Lake cemetery for the burial of pauper dead. The board yesterday agreed to the terms asked by the cemetery officials and directed that the purchase be made.

Hereafter, all pauper dead will be interred in a bona-fide cemetery, instead of being laid to rest in the grounds near the city quarantine hospital in St. Louis Park. The bodies now buried on this ground also will be removed to the new burying ground in Crystal Lake cemetery as quickly as the new plot is put in shape.

The board will take over supervision of the quarantine hospital in January and it is the plan to sell the buildings and ground as quickly as possible. Smallpox patients will be housed in the new contagion hospital at Sixth street and Sixth avenue south after the sale is made.

1916

The 1916 Annual Report of the Minneapolis City Hospitals indicates that there were 93 people admitted to the Quarantine Hospital (presumably the Pest House), 90 discharged, no deaths, and an average stay of 14 days.

The house at 4401 Minnetonka Blvd. was built right next to Potters’ Field. In the 1940s it belonged to the Whalen family.

1917

The 1917 Annual Report of the Minneapolis City Hospitals indicates that there were just eight patients at the Quarantine Hospital at the beginning of the year.

The Minneapolis Board of Charities and Corrections presented its bond requests at a meeting with the Hennepin County members of the House of Representatives on March 9, 1917. Included was a special plea for $75,000 for a new hospital for smallpox patients. Three doctors recommended that the “‘pest house’ now in St. Louis Park should be abandoned forthwith.” (Minneapolis Morning Tribune, March 10, 1917). On March 30 the Board voted to ask the Legislature for power to issue $100,000 in bond to build a five-story addition to the present eight-story contagious ward of the City hospital. Smallpox patients would be quartered on the top floor instead of at the Quarantine Hospital in St. Louis Park. (Minneapolis Morning Tribune, March 31, 1917)

The Minneapolis City Physician was given a choice of employing a new matron at the hospital or to make plans to abandon the building. The latter plan was adopted, and space was made for smallpox patients at the old Contagious Building at the City’s Hopewell Hospital.

A particularly virulent type of smallpox hit the city, brought from Norway on a steamship. Vaccines were not required, but students at the University of Minnesota were declared wards of the State and had to be vaccinated.

CLOSING OF THE PEST HOUSE

1918

The Pest House was closed. John O. “Jack” Johnson rented the caretaker’s house on the property. People referred to “Johnson’s Pest House” and his children as the “Pest House Johnson Kids.” In 1988 daughter Mabel Kruckeberg wrote a letter that says, in part, “I do not know of a jail – there was only a vault building on the property when we were there where they had a few old tomb stones and paper records of some that were buried on the property.”

1919

At the Board of Public Welfare meeting of October 28, 1919, Minneapolis Alderman Rendell brought up the matter of disposing of the quarantine hospital and selling the property to St. Louis Park. He also posed the question of disposition of the bodies interred in the cemetery and requested that the questions be pondered by a joint committee of Health and Hospitals and Public Relief. The motion was approved.

1920

On January 13, Chairman Kunze of the joint committee of Health and Hospitals and Public Relief recommended that the Pest House property be sold as soon as practicable and that the cost of removing the bodies and associated expenses should be deducted from the proceeds and any remaining funds be credited to the Permanent Improvement fund of the Board. The City Attorney affirmed that the power to liquidated the property rested with the City Council and advised that the property should be sold and the proceeds should be credited to the account of the Welfare Board.

In March Jack “Pest House” Johnson requested an extension of his lease of his home on the grounds. Presumably Johnson was the caretaker.

An article (paper unknown) dated April 19, 1920, declared:

Want of Compulsory Vaccination Deplored

Dr. F.E. Harrington, City Health Commissioner, Finds Fault With Law

Severe criticism of the law providing that there shall be no compulsory vaccination for smallpox is embodied in the first health bulletin issued by Dr. F.E. Harrington, city health commissioner… Figures showing 123 reported cases of the disease in the month of February in Minneapolis, compared to no cases at all in Cincinnati and Newark, N.J. and only 16 cases in Chicago are cited in proof of the commissioner’s contention that there is “too much smallpox in Minneapolis.”

“The average large city thinks of smallpox as a loathsome disease of lumber camps, lodging houses or southern negroes in the light of the incidence of the disease in their cities, and truly as a disease of their dark age.

“The law of cause and effect is not inadaptable to this situation. It seems that the Legislature during a somnolent or stuporous period allowed a bill designated to encourage and perpetuate smallpox to become a law. This law took away from the people the right of the state to protect them from those who insist upon remaining susceptible to smallpox, so that they may have it themselves and share with with their friends.

“The preponderance of blame is on the people themselves as did their forefathers against the Indians when there was no legislature, police or health departments to act as their agents.

“Truly it is impossible to recover yesterday or to restore the former beauty of many Minneapolis belles….”

13 new cases of smallpox were reported in Minneapolis in 1920, and ten cases released from quarantine, placing the total number of cases in the city at 155. Between 200 and 300 students whose parents had consented to voluntary vaccination were cared for daily by the five school physicians and ten school nurses. The parents of 500 students from three schools approved of the vaccinations. Physicians were instructed to vaccinate “only such a number each day as will insure the best of care to each.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, November 24, 1920.

1921

In February, 1921, W.W. Carpenter offered to lease part of the property for $10/month. He wished to rent the “Nurses’ Home,” the barn, and the adjacent pasture for one year. At the next meeting in April, Chairman Kunze recommended that the hospital continue as it had been and that the rental should not be permitted. Mr. F.B. Hart offered to relocate the buildings to his property “at little more expense than repairing them on their present location.”

A series of at least five photographs were taken of the grounds on August 2, 1921.

1922

PLANS TO CONVERT TO TB ASYLUM

The City of Minneapolis was looking for a place to establish a hospital for “incurables,” which mostly meant those with tuberculosis. In 1922 they looked seriously at the Pest House site. In an article dated August 9, 1922, it was stated that “The present buildings there are unsuited for a home for incurables… and new buildings would have to be erected if this site is selected.” (Minneapolis Morning Tribune)

On August 17 St. Louis Park adopted the following resolution, which Village Recorder Verner Lindahl sent to the Welfare Board.

RESOLUTION. WHEREAS that portion of St. Louis Park lying between the Minnetonka Boulevard, the Minneapolis & St. Louis Ry., and just west of Indianola Ave. is being closely settled as a residential district, and WHEREAS, such institutions as hospitals for incurables and Detention Hospitals are objectionable in residential districts, therefore BE IT RESOLVED by the Village Council of the Village of St. Louis Park, that the City of Minneapolis, the present owners, or any future owners in St. Louis Park, known as the “Pest House property” and formerly known as such, for any Detention Hospital, or Hospital for incurables of any nature, or for any other similar institution objectionable to the residents of this Village, and BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that a copy of this Resolution be forwarded to the Welfare Board of Minneapolis, and that any attempt to improve siad property as such, that we the Village Council of the Village of St. Louis Park, will serve an injunction on said City, or owner, for any effort made to improve said property with such institutions.

Dr. Ulrich moved that the Board Secretary inform St. Louis Park that it was not the intention of the Board to remodel the Pest House property into a Detention Home or Home for Incurables.

On September 12 Doctors Hugo Hartig, Mabel S. Ulrich, and A.E. Wilcox strongly recommended that the Pest House property should be refitted to receive 100 ambulatory tuberculosis patients because Glen Lake would not be ready for several years and Hopewell Hospital was not large enough for chronic cases and TB patients. Using the Pest House property for TB patients would leave Hopewell available for chronic cases of the kind objected to by St. Louis Park.

On September 13 it was clarified that using the St. Louis Park site for ambulatory tuberculosis patients was just a temporary move. “St. Louis Park residents have threatened to seek an injunction if the board attempts to carry out this program, but board members indicated yesterday they will confer with the St. Louis Park people and believe that when the plan is understood their objections will be dropped.” On September 14 the funds to remodel the Pest House for TB patients was approved by the City of Minneapolis.

September 24, 1922:

Efforts will be made at the meeting of the Board of Public Welfare… to expedite the work of remodeling the city quarantine hospital at St. Louis Park into a 100-bed hospital for ambulatory tuberculosis cases.

On October 2 the Minneapolis Committee of Buildings and Improvements appeared before the St. Louis Park Village Council and presented its plans to improve the property and requested permission to proceed with the construction of the hospital. On October 5 a formal application was made for a license in accordance with Park’s new ordinance prohibiting the construction of a hospital or similar institution without a license. (Apparently they forgot about the one they’d passed in 1892). The application was denied.

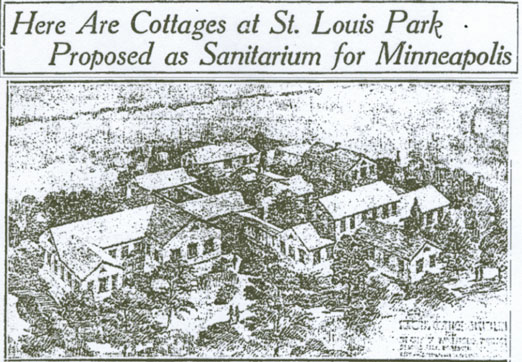

On October 22, 1922, the Minneapolis Morning Tribune published the sketch below. The caption reads: Three quarantine cottages at St. Louis Park on which the Board of Public Welfare proposes to spend $35,000, to be remodeled into a municipal cottage sanitarium for the treatment of ambulatory tuberculosis cases, as shown in the picture. The enlarged buildings will provide 100 beds. The board will meet Tuesday morning to consider a proposal of Alderman T.E. Jenson, a member of the board, who is opposed to the plan on the grounds that the appropriation would provide a cottage at the county institution at Glen Lake, where, he said, very little of the board’s money would have to be expended for administration by co-operation with the county, and the $35,0000 could be used for medical treatment of cases elsewhere.”

Despite St. Louis Park’s denial of Minneapolis’ license, the City threatened to go ahead anyway, saying that as a Village, St. Louis Park had no jurisdiction to license public hospitals. However, the City Attorney believed that the Supreme Court would stand with St. Louis Park if the matter appeared before it. Mr. Hartig sought another opinion from an attorney who had represented Crystal and Robbinsdale in similar matters who held the belief that the Village could not keep a hospital out or prevent improvements. The Welfare Board recommended that City Attorney Cronin’s advice be followed and that an outside attorney be retained to sit with him in the case to avoid conflict of interest questions. The Board then moved to instruct the Building Committee to proceed with improvements pending further legal actions. A Mrs. Hofflin of Hopkins offered some land to the City, saying that “If these people don’t want you in St. Louis Park, come out to my place… Take a look.” Gospel Trumpet Co. offered some land that had been the home to “two old peoples (sic) home… beautifully situated on a terrace about a mile from the Mississippi River.” The TB facility was eventually built at Glen Lake.

“Pest House” Johnson applied for the position of janitor at the new hospital to be constructed in St. Louis Park.

Also in 1922, unbeknownst to them, Ida and Andy Williamette built their house at 4421 Minnetonka Blvd. (at the corner of Lynn), next to the Pest House Potters’ Field. In an article in the Dispatch dated August 6, 1953, the Williamettes said that the cemetery covered an area of about four square blocks and was completely grown over by tall grass and weeds. There were no gravestones. The Williamettes’ house was torn down in 1961 and replaced with apartments.

1923

A survey of all Minneapolis hospital properties valued the Pest House at $3,500 for land, $13,821.86 for buildings, for a total value of $17,321.86.

1924

The Minneapolis Committee on Public Relief notified St. Louis Park that it was considering using the Pest House property for lodging house purposes, and Village Recorder Lindahl again protested such use.

Mr. and Mrs. “Pest House” Johnson were granted permission to remain as caretakers for another year.

Despite the many objections to the property and fear of contagion, there was much interest in obtaining the property; bids were submitted by

- Ann Berdan

- Larmee & Strong

- H.H. Brin

- L.A. Lydiard

The state’s worst smallpox epidemic was declared on November 15, 1924, and lasted until August 1925. Lumber camps were particularly hard hit. In total, 4,041 people came down with the disease and 504 died. Read about it Here.

1925

Additional bids for the property were submitted:

- Hugo Thompson, $10,004. The bid stipulated that the property be conveyed to him by two deeds, one for the burial ground and the balance on the rest.

- Benjamin Faust, $7,000 on terms

- H.H. Brin, $7,756 cash.

- A local farmer offered to buy the water tank, pump, and gasoline engine

- Martin Layman, owner of Layman’s Cemetery, offered to exhume the graves at a cheap price.

1926

On February 23, 1926, the Minneapolis Welfare Board Committee on Penal and Correctional Institutions recommended that the Workhouse Superintendent be authorized to wreck the hospital and salvage useful materials for the Workhouse using Workhouse labor. City Purchasing Agent Gram submitted a survey of Pest House property. An offer was made to buy the pumping equipment. The site was considered for a women’s workhouse, but after meeting with St. Louis Park, a group consisting of Mr. Kunze, Robb, Weil, and Dr. Lockwood decided that the site was not desirable for the purpose and recommended selling it after all.

The Minneapolis City Council received a communication from the Board of Public Welfare on December 21, 1926, about the disposal of the Quarantine Hospital property.

1927

On February 3, 1927, the City Council requested of the Board of Public Welfare a suggestion for disposing of the property. The matter was informally discussed at the Board Meeting of February 8. On March 8, a Mr. Brown reported on his unsuccessful attempts to sell the property. Mayor Leach asked Dr. Lockwood, Superintendent of Penal and Correctional Institutions, to investigate the feasibility of cremating the remains that might be found on the property in order that the land might be sold. When a Board decision was made, it would be submitted to City Council for approval.

At the Board meeting of March 22, Dr. Lockwood reported that the remains could be cremated at Lakewood Cemetery for $50 a box, and that he would take up the matter with Council.

On April 4 the Lakewood Cemetery Association presented a quote of $40 per box for cremating remains. Mayor Leach submitted the following resolution at the meeting of April 12:

WHEREAS the land owned by the City of Minneapolis within the Village of St. Louis Park, formerly used as the site of the former Quarantine Hospital, has been lying vacant and not used for that or any other purpose for over eleven, and

WHEREAS, it does not now appear that there is any likelihood that this land can ever be put to any useful purpose for the benefit of the City of Minneapolis, and

WHEREAS repeated efforts to dispose of this land have failed for the reason that a part of this ground was used many years ago as a potter’s field,

BE IT THEREFORE RESOLVED, that the Board of Public Welfare, subject to the consent and approval of the City Council of Minneapolis and the Village Council of St. Louis Park, will cause the bodies interred on this ground to be removed and cremated at Lakewood Cemetery and the ashes thereof buried in Crystal Lake Cemetery, it being understood that in exhuming the remains care be used that each corpse be kept intact, and their identification preserved as far as possible.

The proposal was submitted to City Council for approval, and Council referred the petition to the Committee on Public Grounds and Buildings on April 22. Public notice was made by the City Clerk on April 25. On April 29 the Council Committee on Public Lands and Buildings recommended that the Welfare Board request be granted. The matter was postponed from the Welfare Board meeting of May 10 to that of May 24. At that time, Mayor Leach moved that the matter be referred to the Committee on Public Health for proper instructions on the removal of the remains.

The following resolution was passed on May 2, 1927, by the St. Louis Park Village Council:

WHEREAS the City Council of Minneapolis has ordered that the bodies interred in the property formerly used as a quarantine hospital be removed from said property and have further ordered that said bodies be cremated and WHEREAS it is to the advantage of the Village of St. Louis Park to have these bodies removed from the Village limits. Be It Therefore resolved that the Village Council of the Village of St. Louis Park do hereby approve of the action of the City Council of Minneapolis and permission is hereby given to the City of Minneapolis to remove said bodies.

At the meeting of June 28, Commissioner of Health Harrington reported that one grave had been dug up and the remains had been found seven feet below the surface. He advised that exhumation should be postponed until the ground dried out.

On August 17 a letter was received from St. Louis Park stating that curb and gutter was ordered for the area around the property and asking if Minneapolis would be willing to pay for this improvement. The Board acknowledged the letter and referred it to the Committee on Buildings and Improvements. Acknowledging that the land would be difficult to sell given the presence of graves on part of it, the Board moved on October 25 that the exhumations should proceed in accordance with the action of April 12, using Workhouse labor under supervision of Drs. Lockwood and Harrington. Apparently there had been at least one bid, from Mr. O.C. Ross, who asked to make another bid.

With the legally-required assistance of a professional undertaking company (Gill), and under the eye of Commissioner Harrington, a workhouse crew began to open the old graves on Wednesday, November 2, 1927. A report from November 8 said “It is impossible to give an accurate count of the bodies removed because of the condition of a great many of them. A careful check will be made to remove all bodies that can be found.”

A special meeting of the Board was held on November 12 to consider problems with the removal of bodies. After cremating only two boxes Lakewood Cemetery found the job to be much more difficult and slow than they had anticipated. Thirty boxes were on hand and more added of every day. Lakewood asked to be released from their obligation and instead offered to bury the boxes for $30 per grave. Dr. Harrington then recommended that cremating be discontinued and that the boxes should be buried in the City plot at Crystal Lake. Superintendent of Public Relief Tattersfield stated that there was plenty of space at Crystal Lake for the bodies to be buried without cremation, and that the cost would only be $4 per box. (Why this vastly less expensive option was not known or considered at the beginning is a matter of conjecture and almost certainly not of public record). It was moved that Lakewood be released from its obligation and arrangements should be made for the remaining bodies to be placed at Crystal Lake.

On November 22, 1927, Dr. Harrington reported that over 1,200 bodies had been removed and that there were at least that many left. It was moved that the Ways and Means Committee take up the matter of funding the expenses of the operation with the Board of Estimate and Taxation to see if a special budget could be set up until the proceeds of the sale of the property could be realized.

At the meeting of December 13 the Ways and Means Committee report was made to the effect that the funding matter had been taken up with the City Attorney and Board of Estimate and Taxation with the result that the estimated cost of $2,500 should be charged to the Permanent Improvement fund of the city and that the City Council would have to set aside from the fund the necessary amount. Also at this meeting, Dr. Lockwood reported that the project should be suspended for the winter due to weather and that over 2,000 bodies had been exhumed and another 800-900 remained.

1928

At the Board meeting of February 28, 1928, Dr. Lockwood said that his crew would resume operations when the frost went out. At the meeting of April 24, the City Comptroller stated that the City Council action appropriating the funds was not sufficient to secure the necessary funding. At the meeting of May 8, Dr. Lockwood asked what could be done next, and Alderman Turner of the Ways and Means Committee moved that the project should continue pending the promise of the funds. City Council responded at their meeting of May 11, resolving to set aside the amount needed from the New Curb section of the Permanent Improvement Construction Fund to complete the removal. The Welfare Board was apprised that the Council was in fact appropriating the money at the meeting of May 22, along with a letter of complaint from St. Louis Park about the “unsightly conditions” at the site. The Board Secretary was asked to reply that the work of removing the bodies and fixing up the ground was not yet completed but soon would be.

On July 10, 1928, the Committee on Penal and Correctional Institutions announced that the project had been completed leaving the property “in a very fine and presentable condition.” A total of 3,000 bodies had been removed “with a possible small error in the final count.” “The ditches dug have been filled and ground leveled off so that the whole is in a very fine and presentable condition.” The Committee commended “the Superintendent and his staff for the very efficient manner in which the work was carried out with Workhouse labor, without any disturbance or any attempt to escape.”

While it seems that the Potter’s Field occupants have been overlooked by history and their fate a possible indignity, all the activity surrounding the business of removing and replanting their remains suggests that a thorough and careful operation took place to assure that they could be afforded a modicum of dignity.

DISPOSITION OF THE BUILDINGS

Despite the information above on the various bids on buildings and equipment related to the Pest House, it is unknown what happened to the buildings. Those who were very young at the time seem to recall a huge fire that burned them to the ground. St. Louis Park fire records don’t go back that far, unfortunately. Bob McCune has been reading through Minneapolis fire records, but hasn’t found a specific reference to a fire here. It is likely, though, that if there was a fire, Minneapolis FD would have participated, due to the proximity to the City and the fact that it may have still belonged to the City at the time.

In 1926 Bob found seven fires in St. Louis Park that were responded to by Minneapolis fire crews. Of those, the following are possibilities:

- April 14: 3700 Excelsior Blvd., 16 minutes

- April 17: undisclosed location, 4:20 a.m., 25 minutes, 2 engines

- April 17: undisclosed location, 10 p.m., one hour, 25 minutes

- April 23: 31st and France, engines #22-28 and ladder #12, one hand water pump; 2 hours and 28 minutes.

- May 28: 31st and “Rochester” (probably Gloucester, now Glenhurst); engines #22-28, hook and ladder #12; 1 hour and 17 minutes.

Bob: “It is quite obvious those 1926 fires were very close to the Pest House location, and upon review of the fire records, it is highly unusual for not only the number of fires to occur, but to have a cluster of fires within a period of two months so close to each other is unheard of in that era. If the fires had to do with the Pest House, the question remains as to why it was not noted in any public record besides the fire logs.”

Thanks to sleuthing by Rick Sewall, we do know what happened to “Pest House Johnson’s” house: From the October 23, 1930, issue of the Hennepin County Review: “Fire, caused by an overheated stove, nearly destroyed what was once the ‘pest house’ for the city of Minneapolis on Saturday night. The house was occupied by J.O. Johnson and family. The interior was practically destroyed and the damage estimated at $4000. Both the village and city fire departments answered the call.”

This was NOT 4105 W. 31st Street, which was once where Johnson lived. That 100+ year old house is still standing.

But there’s this: In a 1962 article in the Dispatch it was reported that the buildings stood abandoned from the time the Pest House was closed until they were demolished in 1930. “The children played in the pest house buildings, after we had been reassured by the Health department that there would be no contagion there,” said Mrs. Johnson. The article said that the caretaker’s house, described as a nine-room, four bedroom home, was destroyed by fire in 1932, but that must have been the 1930 fire. Since two of the men who remember the fire were born in 1925, it’s possible that they would have remembered a huge fire when they were five years old.

SALE OF THE PROPERTY

Minutes of the Village Council were reported in the Dispatch of August 20, 1943:

A letter was read from the City of Minneapolis asking if the village would be interested in purchasing the old pest house property on Joppa Avenue and Minnetonka Boulevard, suggesting if the village were interested that an offer be made. No action was taken.