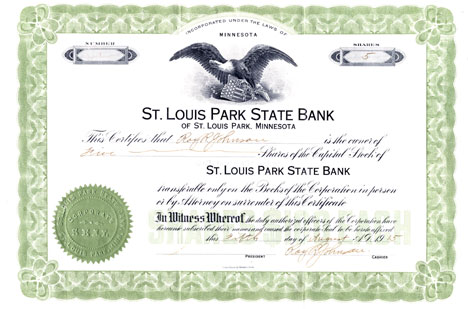

The St. Louis Park State Bank was formed with presumably good intentions. In 1914 Mr. Luman C. Simons of the Twin City State Bank approached the St. Louis Park Commercial Club about starting a local bank. He canvassed potential depositors and sold stock to raise the money.

The next evidence of the bank came on August 9, 1914, when a Professor Hinzerman, “leader of the St. Louis Park Bank,” addressed the Commercial Club on the subject of “what can be done for the amusement of the young people of St. Louis Park.”

The official organization of the St. Louis Park State Bank was announced in the Minneapolis Tribune on May 13, 1915, with building to commence immediately. The bank was capitalized at $20,000 with a surplus of $5,000.

Directors were:

- Roy Quimby, President. Quimby was the president of the Mortgage Security Company of Minneapolis

- W. Fuller, Vice President

- A. Johnson

- John Applequist, the local ice and coal man

- Arthur H.H. Anderson

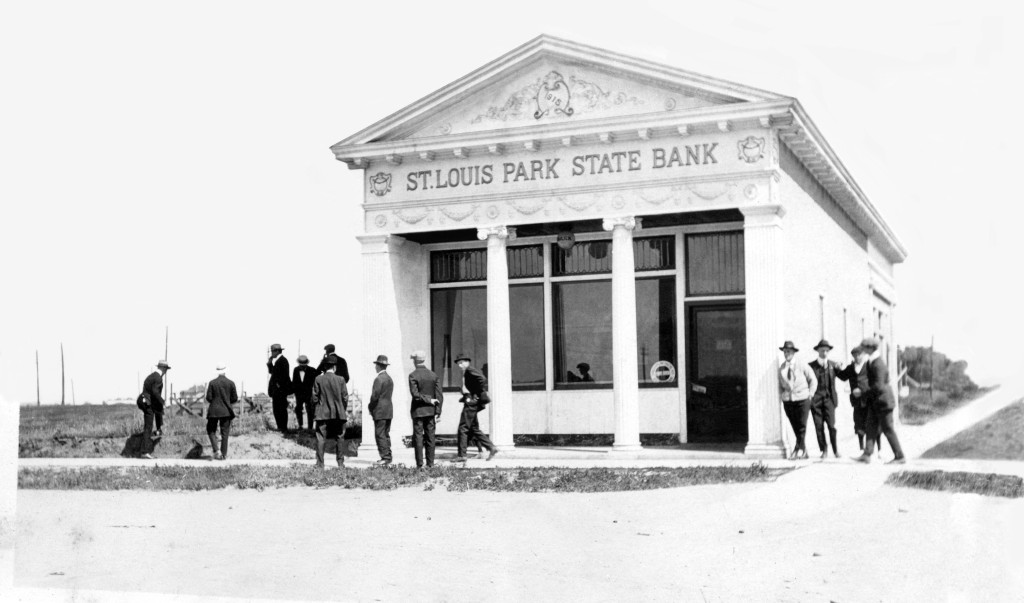

The bank, a Greek revival structure unlike any other in the Park, was built at the corner of Broadway and Main Street, now Walker Street and Dakota Ave. (6400 Walker Street) Despite the names, Walker Street was the village’s main commercial street. Just east of the building, across Dakota, was the new High School, which was the first iteration of what is now Central Community Center.

The bank opened on August 4, 1915, with Roy R. Johnson as cashier. At opening the Tribune reported the $20,000 capitalization, but the surplus was down to $4,000.

At the same time, the Village’s Post Office moved into the rear of the building. Mail carrier Art Blacktin was the first depositor at the bank, irking the Marshall, who wanted the honor.

Soon afterwards, Quimby opened 13 other banks, including:

- Gateway State Bank, Bridge Square, Minneapolis

- Waconia Sate Bank

- State Bank of New Prairie

- State Bank of Chanhassen

- People’s State Bank of Augusta

- Merchants’ and Miners’ State Bank of Tower

- Farmers’ State Bank of Skyberg

- Marine Mills State Bank

- Farmer’s State Bank of Frontenac

- Hamel State Bank

- Farmers’ State Bank of Long Sliding

- People’s State Bank at St. Bonifacius

Everything seemed to be running smoothly, and the bank was designated as the official depository for the Village of St. Louis Park in November 1915. In 1917 it advertised capital and surplus of $24,000.

But trouble started in the summer of 1918 when Quimby sold all 14 banks to William H. Schaefer. Schaefer was a so-called “promoter” who owned Schaefer Laboratories, which made motion picture titles and supplies. The stock was actually issued to a third party, H.C. Kemp, who held onto it for about six weeks. It was then transferred to Charles F. Wyant of Minneapolis, who became President of all 14 banks. But it was clear that Schaefer was in control, and he commenced to rob the banks by having people of limited means such as stenographers and truck repairmen sign promissory notes for large amounts of money and then cash out the notes. This financial maneuver was called “impairment of capital due to insufficiently secured paper.” He was suspected of obtaining $10,000 from the St. Louis Park bank alone through three of these bad notes.

Minnesota Superintendent of Banks Frank E. Pearson caught wind of this scheme and on February 17, 1919, he closed the St. Louis Park State Bank and suspended operations of eight others in the chain. Two days later, on February 19, Schaefer and Wyant were arrested and brought before the Hennepin County grand jury, charged with first degree grand larceny by defrauding depositors of an estimated $700,000. Schaefer’s bail was set at $25,000, but if he tried to raise it, County Attorney William M. Nash vowed that he would add further charges to increase the bail and prevent Schaefer from getting out. Although Schaefer had been arrested that morning at his home, he appeared to be unfazed and was reported to have a “jaunty air” during the arraignment, even allowing the press to take photos of him at will.

Meanwhile, back in St. Louis Park, crowds stormed the locked doors of the bank and had to be dispersed by sheriff’s deputies to prevent them from damaging property. The report said, “Widows and wives of soldiers, fearing destitution by the closing of the St. Louis Park State Bank, literally stormed the offices of County Attorney W.E. Nash last night and today, appealing for relief. The bank, Mr. Nash said, has handled considerable numbers of army and navy allotments for wives of servicemen.” In April 1919, records show the Village repository to be First and Security National Bank of Minneapolis.

The plot thickened when investigators went looking for Schaefer’s assets. It seems that he was having an affair with Minneapolis actress Florence Stone of the Bainbridge Players, who had moved to Chicago. Nash and Detective Thomas P. Gleason traveled to that city to search her apartment for hidden securities. She denied hiding evidence and famously traveled back to Minneapolis for the trial, proclaiming her undying love for the married “Billy,” but did not end up testifying. It did come out that her former husband and fellow actor, Dick Ferris, was blackmailing the pair and may have been the recipient of much of the purloined paper, which was given to him by Schaefer “to shield her good name.”

Shaefer and Wyant were arraigned on March 3, 1919, and pled not guilty. Schaefer’s bail was set at $100,000 for the first degree grand larceny charge. Wyant was charged with accepting deposits – specifically $99 deposited on February 14, 1919, by St. Louis Park storekeeper Charles Hamilton – knowing that the bank was insolvent. Wyant made his bail of $35,000.

One concern of depositors was the issue of Liberty Bonds. Many had been paying for these bonds in installments through the bank. It was determined that all such payments were transmitted to the Federal Reserve Bank and the funds were not comingled with the bank’s assets. Therefore, owners of the Liberty Bonds were entitled to full refunds of the money paid for the purchase of bonds through the bank.

Schaefer’s trial was set for May 1, 1919, with the first indictment that he obtained $3,150 from the Hamel State Bank on two promissory notes of no value. If the State could not prove this charge, it had five others, the second of which was obtaining $10,000 from the St. Louis Park Bank through three worthless notes.

Schaefer went to jail, but not everyone got the news. On June 30, 1919, a would-be bank robber “burst through the doors” of the bank only to find lone cashier L.P. Phillips and no cash. From the Minneapolis Tribune:

“Throw up your hands,” the masked youth shouted, flourishing his gun.

But Mr. Phillips laughed and made nary a move.

“We’re broke, you know,” he told the excited bandit, and placed his pencil over his ear to better contemplate his visitor.

“What do you mean – broke?”

“We’ve been insolvent since February 17 – not one cent will you find here. Do your worst, young man. Go to!”

And the robber’s face, as much as much as protruded from his mask, spelled foiled hopes and shame.

One More Brandish of Gun

“Well, you just keep quiet until I get out.” He had the presence of mind to demand and brandishing his gun once more bean an ignominious retreat.

Mr. Phillips was winding up the affairs of the stockholders and the 11 o’clock visit was diverting and amusing to him.

The young robber fled around a corner, he said, and quickly disappeared. He was in his early twenties, according to the description, well dressed and amateurish.

Bank affairs apparently wound down very slowly. An article in the Minneapolis Tribune from April 13, 1920, reports that a delegation of citizens and former officers and stockholders of the St. Louis Park State Bank filed a complaint with the Governor that the town had been without a bank for more than a year. They later consulted Bank Superintendent Pearson, who said that everything was being done to clear up the affairs of the banks. L.W. Fuller, Vice President of the St. Louis Park Bank and head of the delegation, said that if $11,000 of the questionable paper was cleared up, and organization was ready to reopen the bank.

The bank never reopened. Village Council minutes indicate that the bank officially declared bankruptcy in 1922, with a loss to the Village of $20.07. It would be decades until St. Louis Park once again had its own bank, when a former window washer started Citizens State Bank in 1950.

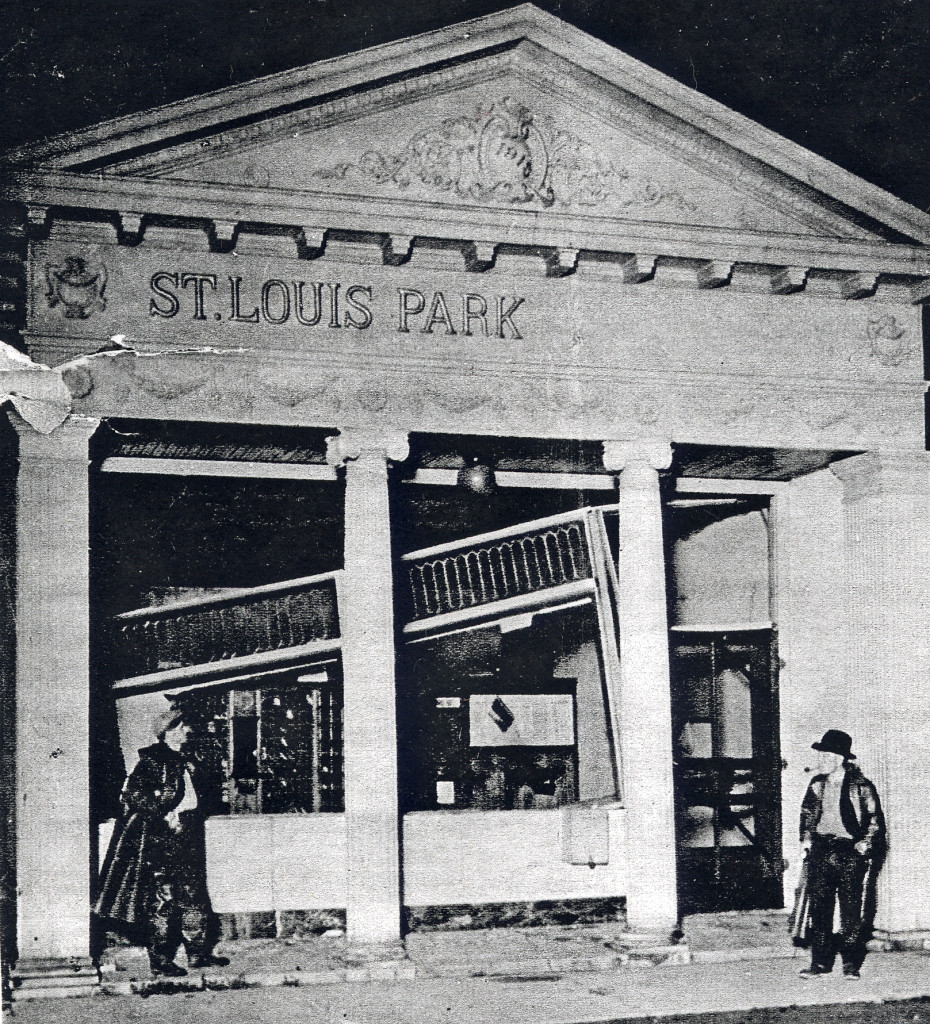

As for the building, the Post Office, which had been located in the back, moved up to the front. One source says that the building was purchased by Robert E. Scott, superintendent of schools, and John Freeland, local grocer. The building was severely damaged in the June 25, 1925 tornado, as shown below. The Post Office moved out in 1937.

For many years there was a snack shop in the back that served decades of high school students.

It is unclear what happened to this building. An aerial photo in the 1954 Echowan shows that it still existed. However, tax records seem to indicate that the present building at this location was built as a one-story building in 1952 for the M.L. Gordon Sash & Door Co. as a warehouse. It is completely surrounded by loading docks. It now belongs to the school district and is used as a Grounds Shop: it holds all the district’s grounds equipment, trucks, etc. and is also where their mechanic repairs vehicles and other equipment. Perhaps that old, ill-fated bank building is still there under the bricks, giving no hint of the financial hopes and dreams of our Village so many years ago.