This chapter acknowledges the importance of the automobile (and the bicycle before it) in the development of St. Louis Park. See our page on Cars and Roads for links to the histories of specific thoroughfares in the Park.

Park’s first residents were served well by T.B. Walker’s streetcar, which ran from Park’s “Industrial Circle” to downtown Minneapolis. Brookside residents came to the area as a result of the 44th St. streetcar, and could also get downtown via bus down Excelsior Blvd. Before the War it was only dad who worked, and mom could get her groceries delivered, so a family car was not necessary (and often not affordable). During the War, cars, tires, and gas weren’t available anyway. But during the postwar boom, the growth of the city went beyond the reach of public transportation, and newfound prosperity enabled Park residents to finally buy the automobiles that had eluded them for decades.

As a result of this postwar love affair with the automobile, Park’s boosters promoted its highways as a tremendous advantage, touting the town as “out where the highways meet.” One of those highways was the state-of-the-art Highway 100. Another was Excelsior Blvd., a very old road that ran directly into Minneapolis. The intersection of these two highways, located at the northeast corner of the Brookside neighborhood, formed the hub of commercial life in the southernmost part of the Park.

One of the most striking examples of the importance of the automobile to the local economy was all the gas stations that lined Excelsior Blvd. See Excelsior Blvd: Gasoline Alley for the list of these gas stations.

There are many great sources of information about cars and highways. Automobile factoids in this section came from Divided Highways by Tom Lewis. Although this book is mostly about the Interstate Highway System (394 is the only Interstate relevant to Park), it is full of great information about American highways in general. AAA’s website is interesting, as is Mn/DOT’s History web page. Also see our page on Taxicabs.

Although it does not pretend to be comprehensive, the following timeline includes some pivotal national, state, and local events that provide evidence of the automobile’s importance in the economic and social growth of St. Louis Park. This timeline also traces the history of some of the area’s highways, so important to the people of the Park.

One interesting factoid is that it took 55 years for a quarter of the U.S. population to own an automobile. The cell phone took only 13 years.

Keep in mind that St. Louis Park did not exist as a Village until 1886.

1849

Territorial law required all males between the ages of 21 and 50 to spend two days each year working on roads.

1850

Congress passed the Minnesota road act on July 8, authorizing five “government roads” (intended for ox-cart traffic), most of which are now abandoned.

1851-54

The Territorial government authorized the Minneapolis and Lake Minnetonka Plank and Road Company to build a plank road which may have been the precursor to Highway 12.

1858

Shortly after Statehood, the Minnesota legislature began regulating road and bridge buildings, but didn’t actually build anything itself. During the first three years after Statehood, a stage and wagon road was built to supplement the oxcart trails that had been established in the 1830s.

1860s

The first bicycles were created in France and featured front-heavy big wheels that made riding them dangerous and restricted to healthy and wealthy young men. These bicycles were called “ordinaries” or “penny-farthings,” after the large and small penny and farthing English coins. It was very easy to hit a bump and go sailing over the handlebars.

1886

The first successful gasoline-driven automobile was patented by Carl Freidrich Benz, who competed against fellow German Gottlich Wilhelm Daimler. When Daimler died in 1900, the company was renamed after Mercedes Jellinck, the daughter of an influential French distributor. The two companies merged in 1926.

1878

Albert Augustus Pope invented his “safety bicycle” in 1878. It balanced out the size of the two wheels and made the contraption more accessible to the masses. Bicycles began to be imported to the U.S. Pope also introduced mechanization and mass production to the manufacture of bicycles, and advertised aggressively. Costs came down with the introduction of stamping instead of machining each unit. Even so, says Wikipedia, bicycling remained the province of the urban well-to-do, and mainly men, until the 1890s, and was an example of conspicuous consumption.

1885

John Kemp Starley, produced the first successful “safety bicycle,” the “Rover,” in 1885, which he never patented. It featured a steerable front wheel that had equally sized wheels and a chain drive to the rear wheel.

1887

The Village Council voted to purchase two planks, to be placed in a V shape, to be used as a snow plow.

1888

John Dunlop’s improvement of the pneumatic bicycle tire in 1888 made for a much smoother ride on paved streets; the previous type were quite smooth-riding, when used on the dirt roads common at the time.

1890

The safety bicycle completely replaced the high-wheeler in North America and Western Europe by 1890.

1892

The first successful internal-combustion car was built by the Charles E. and J. Frank Duryea.

Early 1890s

The Stanley Brothers put a steam-driven car on the market. These proved to be hazardous, especially when one was hit and hot water scalded the driver. The Stanley Brothers also produced the Locomobile, a cheaper car made under the same patent. (Note that one source describes the Locomobile as an expensive, two-seater roadster.)

1893

Bicycle prices dropped in the 1890s, and America experienced a bicycle craze, especially from 1893-97. Bicyclists formed the League of American Wheelmen to lobby for better roads and facilitate riding with maps and hotel discounts.

According to British geneticist Steve Jones, the advent of the bicycle was “the most important event in recent human evolution.” The reason? People could travel to other towns and were not restricted to marrying within their own immediate area, thus widening the gene pool!

1894

The first auto show was held in Chicago.

Section 14 of the Village ordinance states: “While cars are turning corners or crossing bridges, the horses or mules attached shall not be driven faster than a walk.”

1895

A Minneapolis newspaper reporter brought a car to the 1895 bicycle show, and that was considered to be the first automobile in Minnesota. Shortly afterwards, the A.E. Chase Company of Minneapolis became the sales agent for the Oldsmobile, which was known as the “rolling peanut.”

1896

In October 1896 the road crew consisted of Ed. Long, Wm. Falvey, C. Hamilton, D.J. Falvey, Chris Johnson, August Ohde, Andrew Triden, Joe Williams, Wm. Dillaboe, Frank Rice, and Mike Young.

In 1896 Minnetonka Blvd. was a narrow bicycle path.

1897

After much debate, the term “automobile” became the name of choice for the increasingly popular machines, according to the New York Times. It had already entered the French language in 1895.

The St. Paul Dispatch pictured what it called the first automobile in the Twin Cities, on May 29. The car was owned by H.J. Schley, who used the machine to advertise his cigarmaking business.

Around this time, Joe Williams reported that the first horseless carriage “was first demonstrated at the State Fair one year when the Park Band was playing there. They would drive around the grounds for about 15 minutes at a time and then come back to have the battery charged.”

1898

On August 5, 1898, the St. Louis Park Village Council passed an ordinance authorizing the construction of bicycle paths/roads on South Lake Street and South Minnetonka Blvd. The speed limit was 10 mph, with fines of $10 to $50 or up to 30 days in jail.

An amendment to the Minnesota Constitution allowed the State to build roadways, although that did not happen until 1905.

Genevra Delphine Mudge became the nation’s first known female driver, navigating her Waverly Electric automobile in New York.

1899

On May 23, 1899, St. Louis Park passed an ordinance prohibiting bicycle riding on the sidewalks (which were probably boards).

The Automobile Club of America, predecessor to the American Automobile Association, met for the first time in New York on October 16.

St. Paul police had a problem with speeding bicyclists, so they organized a squad of 12 officers to patrol the roads on bicycles of their own. The speed limit was 6 mph on sidewalks and 8 mph on the streets. Speeders were derided as “scorchers.”

1900

In St. Louis Park, the Village paid Chris Johnson for “roadwork,” although this may still have been for horses and buggies.

More bicycle paths were laid out in 1900. In June 1900 an ordinance required riders to obtain a 50 cent license.

Minneapolis residents had 13 cars, and on August 11, they all raced from the Hennepin County Courthouse to Wayzata. The winner did the 12 miles in 42 minutes. The point was to demonstrate the need for better roads.

The first automobile showroom opened in New York City.

No date, but the first auto dealer in Minneapolis was A.F. Chase, who sold the Tiller Handled Oldsmobile, according to Win Stephens’ biographer.

The nation had 160,000 miles of roads in 1900, as compared with 250,000 miles of railroad.

There were 8,000 cars in the entire country.

There were over a million bicycles on the road, made by over 300 manufacturers. The demand for good roads resulted in the creation of the U.S. Office of Road Inquiry under the Department of Agriculture. This office later became the Bureau of Public Roads. Local bicyclists petitioned the village to build bicycle paths, but traditionally conservative Village fathers were hesitant to spend the money.

The German car exhibited at the World’s Fair in Chicago was the only one in America.

1901

The Village paid William Falvey and crew for roadwork. Chris Johnson was also doing roadwork, plus work on bicycle paths, which were apparently made out of cinders.

A Village Street Commissioner was hired at a rate of $2.50 per day.

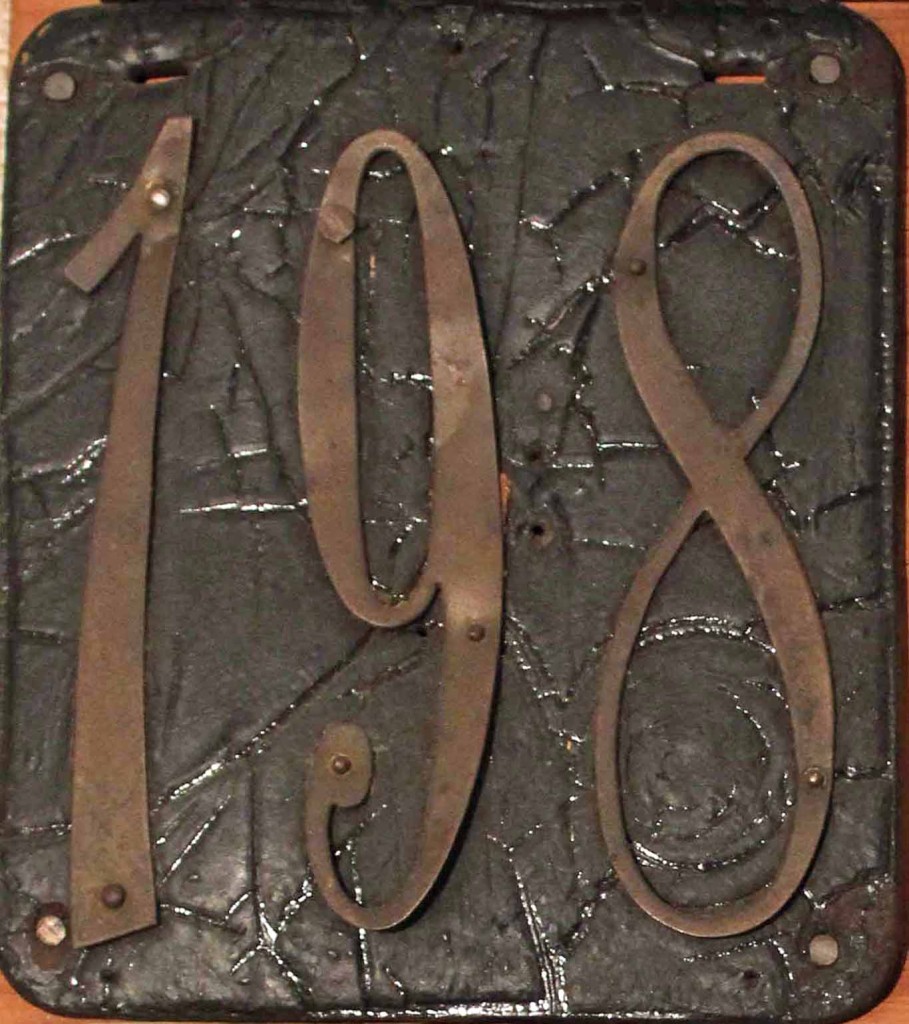

States began to require automobiles to be registered, although plates were sometimes do-it-yourself affairs.

1902

On August 1, 1902, the Park Village Council passed an ordinance regulating the speed of “automobiles, autocars, or other vehicles of pleasure or burden propelled by electricity, steam, gasoline, compressed air, orother similar motive power.” The 10 mile speed limit was enforced with a $50 fine or up to 30 days in jail.

Dr. John Watson was said to have the first car in the village, a one-cylinder Oldsmobile trimmed with brass that the locals called a gasoline buggy. It had to be cranked on the side, and was steered by a lever or handle at the end of a steering rod. Any horses in hearing distance always reared right up at the sound of it. The car didn’t work out too well in Dr. Watson’s practice and he soon returned to using his horses. (Pioneer Physicians of Hopkins, Minnesota by Jeanette D. Blake)

The Moldestad farm was north of Minnetonka Blvd., but there was no direct way to get there from what is now 26th Street. In about 1902, J.J. Moldestad petitioned the Village Council for a public road. The Council provided the grading and Moldestad saw that the land was cleared of trees. That road is now Zarthan Ave.

At the behest of citizens, the Village Council authorized the building of bicycle paths to the extent the treasury would permit.

There were thought to be about 125 automobiles in Minneapolis.

The American Automobile Association was formed in Chicago. The Automobile Club of Minneapolis was formed in the fall, its stated objectives being “the instruction and mutual improvement in the art of automobilism and the literary and social culture of its members.” One of the reasons that Automobile Associations were being formed around the country was harassment from farmers and city officials, some of whom passed speed limits as low as… 10 miles per hour… Opposition came from farmers whose horses were spooked by the “devil wagons,” buggy and wagon makers, and blacksmiths, although the latter transitioned into automobile mechanics.

1903

1903 was a big year for sidewalks, which at this time were made of wood. Typical specifications were 2 inch by 6 inch pine planks, 4 ft. long with stringers (?). Also 4 by 4 inch planks to be laid crosswise.

Minnesota passed its first traffic laws and began requiring the licensing of automobiles, except where municipalities had already begun to do so. 920 vehicles were registered that year. License Number 1 was issued for a Packard belonging to R.C. Wright of St. Paul.

In 1903, Henry Ford, the chief engineer of the Edison Electric Plant in Detroit, started the Ford Motor Company in a converted wagon factory. The new company produced the first version of the Model A.

Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson and his personal mechanic/chauffeur made the first cross-country trip from San Francisco to New York. They drove a Winton, and it took 63 days.

Cars were first enclosed and given glass windshields.

Bicycles were required to be registered; tags for 30,000 bicycles were issued in the City of Minneapolis.

1904

Ford came out with the Model B. Steering wheels replaced tillers.

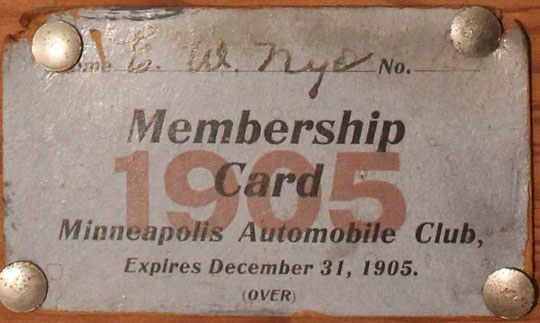

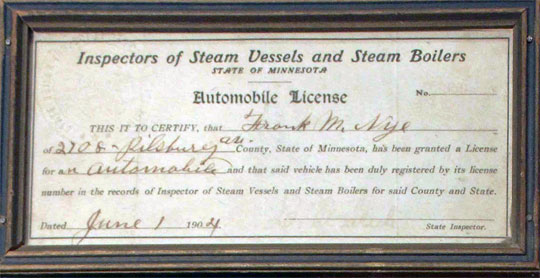

FRANK NYE’S CADILLAC

On May 28, 1904, Frank Mellen Nye of 2708 Pillsbury Ave. in Minneapolis was issued Minneapolis Automobile License 198 for his Model “B” Cadillac – 1 Cylinder – 8 1/2 Horsepower – 76″ Wheelbase – Delivered cost $950. Purchased from Pence Automobile Co., 3rd Street and 4th Ave. So., Minneapolis. The paperwork was made into a plaque and saved by his family for over 100 years – Frank’s great grandson Mike Nye was nice enough to send a photo of it to us, since his grandfather, Edgar W. Nye, also lived in the Park, at 4814 Vallacher. Read more about Congressman Frank Nye below the photos.

Frank Mellen Nye (March 7, 1852 – November 29, 1935) was born in Maine and moved to Wisconsin with his parents at the age of 3. He became a lawyer in 1878, first practicing in Hudson, Wisconsin, then serving as district attorney of Polk County, Wisconsin from 1879 to 1884. He was a member of the Wisconsin State Assembly in 1884 and 1885. He moved to Minneapolis in 1886 and continued to practice law. From 1893 to 1897 he was an assistant and then prosecuting attorney of Hennepin County. In 1901 Nye won a celebrated case defending a Granite Falls dentist who had killed a crooked gambler; the prosecutor in the case was none other than Andrew Volstead, later notorious for the Volstead Act that enforced Prohibition. In 1904, at age 52, Frank Nye bought his Cadillac. He was elected as a Congressman (Republican) in 1906 and served from March 4, 1907, to March 3, 1913. In 1911 his son was a driver to President William Howard Taft (see 1911 below). Nye declined to be a candidate for renomination in 1912 and resumed practicing law in Minneapolis. By 1920 he lived at 4500 W. 44th Street in St. Louis Park (on the cusp of Edina), a house built in 1910. In 1920 he was elected judge of the district court of Hennepin County for a six-year term and reelected in 1926, serving until his retirement in 1932.

1905

The Village obtained cinders from the Interior Elevator for use in road and/or bicycle path building.

The Minneapolis Tribune published a list of 1528 people who held automobile licenses on May 13, 1905. The only one from St. Louis Park was an F. G. Decker, who was number 917 on the list.

The State legislature created a three-member highway commission to distribute state road building funds to hard-pressed counties for the first time.

There were approximately 8,000 cars in the U.S. and 144 miles of paved roads.

“My Merry Oldsmobile” was written, and it was a smash. In it, the singer coaxed his girlfriend Lucille to run away with him. It wasn’t written at the behest of Oldsmobile, but Olds appreciated the publicity and gave the two authors a car. Nice publicity stunt, but two men couldn’t own one car, so they sold it and split the money.

1906

In 1906 we start to see entries in the Village Council minutes to indicate that sidewalks were now being made out of concrete block.

Speed was the subject of another Village ordinance, both for railroad engines and automobiles.

Despite the popularity of the song “In My Merry Oldsmobile,” not everyone was enamored of the automobile. Woodrow Wilson, still the President of Princeton University, was quoted as saying “Automobilists are a picture of arrogance and wealth, with all its independence and carelessness… Nothing has spread socialist feeling in this country more than the automobile.”

Ford developed the Model K, which was just as much of a disaster as the “K Car” of the 1980’s.

1907

The St. Louis Park Good Roads Club made a request that Enide Boards (?) be placed at all crosswalks in the Village.

Minnesota’s first state automobile license laws were enacted. Before that, cities individually licensed their drivers. [from another source: Rhode Island passed the first driver’s license laws in 1908, followed by New Hampshire in 1909.]

Local Automobile Associations combined to form the Minnesota State Automobile Association, its purpose to procure “fair and equitable automobile legislation and Good Roads for Minnesota.”

1908

William Crapo Durant, a buggy maker from Flint, incorporated General Motors by buying several fledgling automobile companies such as the Rapid Motor Vehicle Company. He later lost control of the company and went on to found the Chevrolet.

Ford came out with the Model T, which was adapted from the Model N Runabout of 1906. With an average cost of just $400, the Model T created the first mass market for automobiles. By 1924, a Tin Lizzie could be had for as little as $290.

MINNEAPOLIS AUTOMOBILE CLUB

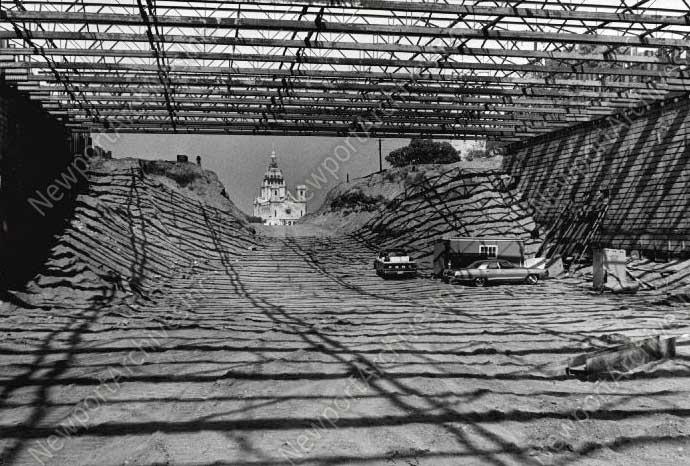

In 1908 members of the Automobile Club of Minneapolis built the AAA Auto Club Country Club on a 10-acre site at Bloomington-on-the-Minnesota on the Minnesota River Valley Bluffs. It was located on the south side of Auto Club Road, southwest of the Minnesota Valley Golf Club on what is now called Bluff Drive. This facility became a dinner and dancing spot for Club members.

The original building burned to the ground in 1918, allegedly torched by a disgruntled maintenance man. The club was rebuilt in 1919 in the style of a Swiss chalet; a 1920 news article called the area “Little Switzerland.” The Club House building and the beautifully landscaped grounds on the edge of the Minnesota Valley Bluffs were an outstanding sight and the Club with its excellent chefs and service was a very popular place for diners. It was open between Mother’s Day to Labor Day. Members built a road to the location from Minneapolis.

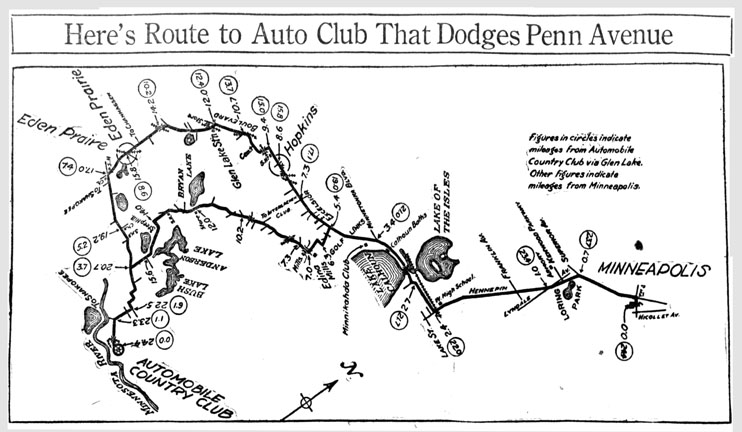

The Minneapolis Morning Tribune provided the hilarious map below for members of the Minneapolis Automobile Club to use to get to their Bloomington Country Club from the city without suffering the rutted Penn Ave. It instructs you to take Excelsior Blvd. west to France Ave., then 44th Street to Browndale station. Once through Edina Mills, you will be confronted with three roads – take the one straight ahead, which goes through the village of Roland, on Bryan Lake. Roland consists of one store. Next turn to the left on “upper Shakopee road.” There are signs all along the way – you can’t miss it. Here’s the map:

St. Louis Park High School had its school Prom in the building in 1940, with special permission to hold it one day before its grand opening for the year. In 1949 there was a problem when the manager of the ballroom found out that a Jewish student was planning to attend that year’s Prom, and threatened to bar him. St. Louis Park Superintendent Harold Enestvedt told him that if all his students were not welcome, the Prom would be held elsewhere. The manager backed down. The incident demonstrated the anti-Semetic stance of the AAA in its early years.

The facilities were not designed for winter use and eventually became uneconomical to operate as a seasonal business. In the 1958 the buildings were demolished and the grounds were developed into homesites.

1909

Monitor Drill owner SE Davis had a Lozier; previously he had a White Steamer.

GM purchased the Cadillac Automobile Co., which was derived from the Detroit Automobile Company in 1902. Cadillac is named after the founder of Detroit: Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac.

In Minneapolis, there were Glidden Reliability Automobile Tours in 1909, according to Win Stephens’ biographer.

1910

Four speed signs were ordered for Minnetonka Blvd. at the request of T.H. Colwell.

In Minnesota, 15,150 cars were registered.

The first Minneapolis Auto Show was held at the Kenwood Armory.

1911

GM purchased the Chevrolet Motor Car Company, named after race car driver and designer Louis Chevrolet.

Studebaker first offered cars on the installment plan, starting a slippery slope of American consumer debt.

DRIVING PRESIDENT TAFT

In 1911 President William Howard Taft toured the western United States to drum up support for his arbitration treaties with England and France. On October 17 he spoke in Winona, Minnesota. He spoke at the University of Minnesota on Tuesday, October 24, 1911. An article the next day in the Minneapolis Morning Tribune said that in his address Taft “spoke fondly” of the work of Cyrus Northrop who had retired earlier that year as the University’s president. Taft’s references to Northrop were “cheered by the students.” A writeup in the Minnesota Engineer describes:

President Taft, while in the Twin Cities, visited the University. All fourth hour classes were excused so that as many as possible would have an opportunity of seeing the President of our country. The University Cadets, under direction of Major Butts, performed the military part of the reception.

When Mr. Taft arrived he was greeted by hurrahs and “Hail to the Chief.” Immediately after this the entire audience sang the “Yale Boola Song, which was followed by Minnesota yells.

President Vincent introduced President Taft by saying that he was a college man in politics and had raised the standard of politics from mere personal ambition to public service. Mr. Taft then spoke of the duty of University graduates to the public, telling how much better fitted they were for service than those who had not had the advantage of a college training. He expressed his views on athletics, saying that he did not like acts of rowdyism. Politeness of individuals was another topic.

All this is under Automotive Milestones because we have a photo of Congressman Frank Nye’s son (see 1904 above) driving President Taft during his visit to Minneapolis, courtesy of Nye’s great grandson, Michael Nye.

No President would visit the Twin Cities again until President Bush (private event) and several visits by President Obama.

1912

In July, Dr. G.M. Wade of the Brookside Improvement League requested approximately $300 from the Village Council to build “cinder paths.”

On August 1, 1912, the St. Louis Park Village Council passed an ordinance regulating the speed of “automobiles, auto carts, or other vehicles of pleasure or burden propelled by electricity, steam, gasoline, compressed air or other similar power.” The speed limit was set at 20 mph.

THE YELLOWSTONE TRAIL

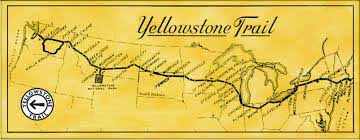

The Yellowstone Trail was an east-west route for automobiles to follow in the very early days of auto traffic. As its name implies, the route was marked by various kinds of painted stones or embossed metal or painted signs with the official circle and arrow of the Yellowstone Trail Association (YTA). The YTA was formed in October 1912 and was active until 1930. Headquarters were in Minneapolis. There were also local Yellowstone Trail Associations along the route. The Trail first began with 25 miles of road suitable for automobiles in South Dakota.

It was part of a system of colored markings (see 1915 below). Hopkins reports yellow-striped telegraph poles running through town, and presumably St. Louis Park had the same markings. To get on the Yellowstone trail, take the Green trail to Lake and Hennepin, where you pick up the Yellow trail to Excelsior, Waconia, Granite Falls, Yellowstone Park, and Seattle. As far as we can tell from a 1919 brochure published by the Association, the trail did run along Excelsior Blvd. through St. Louis Park. It was declared one of four military roads during WWI. In 1927 there was a Yellow Trail Garage in Hopkins, operated by A. Shimota. For some reason one could buy a gallon of 188 proof alcohol for 80 cents here, despite being in the middle of Prohibition..

Encouraged, founder J.W. Parmley of Ipswitch, South Dakota, and his associates proposed “a good road from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound.” The Association did not build roads, but lobbied government entities for “good roads.” Businesses in small towns along the way raised funds to improve their roads. No Federal funds were used to improve the roads.

For more information on the Yellowstone Trail, see www.yellowstonetrail.org.

In 1912 Leslie H. Fawkes, one of the first automobile dealers in Minneapolis, bought an estate in St. Louis Park called Cobble Crest. Fawkes came to Minneapolis from Illinois in the 1890’s and opened a bicycle shop in 1893. With the advent of the auto, the company became the Great Western Cycle and Automobile Co. Fawkes sold the REO Speedwagon, the Cord sports car, the Auburn, and the Overland. He built the Fawkes Building at Hennepin Ave. and Harmon Place, then the place to go for an automobile for many years. The Depression affected his suppliers, and thus put him out of business. Shortly afterwards, he had to sell his country home in St. Louis Park.

The Dunn amendment revised the State constitution again, allowing a tax for roads. Roads were classified as either State, county, or township roads.

The three state road commissioners were authorized to appoint 45 engineers.

AAA copyrighted its first map. Rand McNally, a Chicago cartographer, issued his first national road atlas in 1924.

Henry Leland invented a self-starter after a friend of his died of injuries received from the kickback of a hand crank. [perfected by Samuel Kettering]

The first light-based traffic signals were installed in Salt Lake City and featured roofs to protect them from rain and snow. Their two settings, “stop” and “go,” were manually operated by a police officer.

1913

A concrete sidewalk was installed at the Streetcar station.

It is unclear just how the Council determined which roads would be improved, but there are many instances where a group would come before the Council to request work to be done. A committee would inspect the conditions, and the results would flow from there. Whether this proactive approach was necessary in order to get a road graded is not known. An example was when Ora Baston petitioned the Council to put Highland Ave. (36th Street) from Railway Ave. (no such street?) to Excelsior Blvd. “in a good condition for use.”

Automobiles were becoming affordable to working folks – Minnesota had about 45,000 automobiles. An ad from the Minneapolis Journal dated 11/2/1913 listed Dealers in Automobiles and Accessories.

In the early days, there was a dizzying variety of automobiles to choose from. Here is a listing, taken from the 1913 ad and Win Stephens’ biography:

Alco

Apperson

Bergdoll

Brush

Cartercar

Chandler

Cole

Detroit Electric

Dreadnaught Moline

Elgin

Elmore

Empire

FIAT

Havers Six

Herreshoff

Hupmobile

Jackrabbit

Keaton

King

K-R-I-T

Liberty

Little

Locomobile

Marathon

Marion

Marmon

Maytag

Metz

N.W. Cole

National

Oldsmobile

Paige

Pathfinder

Pierce Arrow

Pope

Rambler

Rickenbacker

Simplex

Speedwell

Stanley Steamer

Stephens

Stevens-Duryea

Velie

Winton

Harley Davidson and Indian motorcycles were also for sale downtown as well.

Minnesota’s first Good Roads Day was declared on June 17, 1913.

Gulf opened up the first station in Pittsburgh in 1913.

1914

St. Louis Park passed two ordinances with regard to automobiles in 1914. The first, in August, amended the ordinance of 1912, changing the speed limit to 25 mph. The second, in October, was much more specific. It seemed to indicate that automobiles were only allowed to drive on Excelsior Blvd., Lake Street Blvd. (sic), Minnetonka Blvd., and Superior Blvd. (now 394). The ordinance required autos to have headlights, mufflers, brakes, and a manner of signaling (bell, horn). There were still plenty of horses around: “Every person operating a motor vehicle shall stop upon request or signal from any person in charge of a horse or horses; and shall also stop whenever a horse or horses show signs of fright at the motor vehicle.” This ordinance also ended with a 25 mph speed limit – on the specified roads.

The Minneapolis Daily News reported that there were 15,000 automobiles in Minneapolis, and 50,000 registered in Minnesota.

The St. Louis Park Commercial Club stressed to the Village Council the importance of marking streets and numbering houses. The Commercial Club was also making a concerted effort to attract the rubber-making factories of Ohio, another potential superfund site that fortunately didn’t happen.

Nurseryman Ruedlinger sold the Village 75 elm trees for planting at $1.50 each.

Mark Pavey, who must have been a constable or marshal or similar, spent time catching speeders, and billed the Village for a percentage of the take. The next year, it was Andrew Pavey “flagging autos.”

Hungry for good roads, automobile associations were shelling out their own money to build them.

The Minneapolis Automobile Club spent several thousand dollars to grade, oil, and improve roads in Hennepin County.

The first manual traffic signal was installed in Detroit. Date unknown, but Woodward Avenue in Detroit, Michigan, carries the designation M-1, named so because it was the first paved road anywhere.

The first electric traffic signal was installed in Cleveland – date unknown.

Henry Ford began to mass-produce the Model T in “any color so long as it is black.” These sturdy, reliable cars were manufactured until 1927. Ford paid his workers $5 per day, so that they could afford to buy the products they made (and to create a market for the products they bought). Ford offered a conditional rebate for the end of the year: if he sold 300,000 cars by the end of the year, each purchaser would receive $50. About that time there circulated the “Ford Joke Book.” Once such funner: “the Ford didn’t need a speedometer because at twenty miles per hour the doors would rattle; at thirty, the headlights would rattle; at forty the fenders would rattle; at fifty the top would fly off; and at sixty, a record would play ‘Nearer My God To Thee.”

1915

On July 25, 1915, the St. Paul Pioneer Press explained the system of markings on telephone poles that constituted road signs in those days. There could be a colored stripe between two white stripes, a combination of stripes, or a set of symbols that told you what direction to turn or where there was a garage or hotel. Trails were color coded:

- The black trail went to north to Duluth and south to DeMoines – the southern section was called the Capitol National Highway and the Interstate Trail.

- One green trail went to Superior. Others went to Aberdeen, South Dakota and Minot, North Dakota.

- The red trail went east to New York and west to Seattle. The Red Ball route went to St. Louis.

- There were two or three blue trails; the one out of St. Paul went to Rochester.

- The Yellowstone Trail was yellow and black (see 1912 above).

The telephone poles were repainted every year by private companies that were hired by hotels or guidebook publishers. In remote places without such poles, they set up stone markers.

In November, citizens of Brookside complained about the poor condition of the bridge where Brookside Ave. crossed Minnehaha Creek. The Council ordered the bridge replaced at once.

Apparently removing dirt from streets and alleys was a common enough occurrence that the Village Council found it necessary to pass an ordinance forbidding such activity, at least not without asking first.

AAA’s first emergency road service was started by the Automobile Club of Missouri, and spread across the country by the late ’20s.

The Ford Plant in St. Paul manufactured its first automobile on May 4. The Mayors of the Twin Cities participated in the celebration.

1916

The Federal Aid Road Act was the first Federal law providing funds to the States for rural post roads. In the first year, $5 million was provided to states – $75 million over five years.

The Minnesota Scenic Highway Association was founded to promote to promote auto travel. It encouraged commercial development along roads by naming and marking highways before such identifications were standardized. The Minnesota Scenic Highway was marked with blue signs with a white star. Other highways were marked by color-coded poles instead of route numbers.

1917

A Mr. Boostrom donated brick that was salvaged from the Walker Block fire to the Village. It was to be place on Main Street (Dakota) between Broadway (Walker) and Lake Street.

The Minnesota Highway Commission was abolished, and the Minnesota State Department of Highways was authorized. . Charles M. Babcock of Elk River was chosen to be the first commissioner and was empowered to employ a support staff and a deputy commissioner who must be an engineer as well as road builder.

At the end of WWI, the debate between the horse and the auto was decided in favor of the machine. One reason was that it required five acres of land and 20 man-days of work per year to keep a horse. Horses were by no means obsolete, however – they could be seen as late as the 1930s, mostly hauling delivery wagons.

Cars began to come with heaters.

1918

In 1918 an ordinance was passed regarding “Jitney buses.” The word jitney may mean that the ride cost a nickel.

Another ordinance prohibited drivers from getting in the way of the fire truck.

The Ten Thousand Lakes of Minnesota Automobile Association was founded.

Wisconsin became the first state to number its highways.

1919

In June the Village Council decided to purchase “one Hi-Way Patrol and two road drays.” Notice was put up in the three most public places in the Village: Lake Street and Broadway (Walker Street) Excelsior Ave. and Brookside, Lake Street and Glouchester (Glenhurst).

The Council also voted to purchase a “Boon Auto Service Book” for no more than $30.

Thomas Harris McDonald became Chief of the Federal Bureau of Public Roads, then under the Department of Agriculture. He would keep his position until the Eisenhower Administration.

On February 28, 1919, the Secretary of War was authorized to distribute excess war material to the Department of Agriculture to distribute to the states for use in constructing highways. The excess material included trucks tractors, and other heavy equipment. By the end of 1920, Minnesota had received 632 trucks.

General Eisenhower made a cross-country automobile trip that took 62 days to complete because Army vehicles only got up to five miles an hour.

The world’s first three-color traffic lights were installed in Detroit. Two years later they experimented with synchronized lights.

1920

Cinder paths were still being used, even on Excelsior Blvd. The Village got the cinders from the Creosote plant.

On August 5, 1920, the Village passed a comprehensive ordinance that spelled out the rules of the road. It required mufflers and turn signals, and required the use of dimmer lights. Speed limists were 10 mph on built up portions of the village or where traffic ws congested; 15 mph in reidential areas, and 25 mph for highways. Doctors on call were exempt. The ordinance included horse-drawn buggies, carts, drays, wagons, hackney coaches, omnibus, taxicabs, carriages, buggies, motorcycles, automobiles, tricycles, bicycles, or other vehicles used, propelled or driven upon the streets of the village. Excluded were street cars and baby carriages. Equestrians were instructed to raise their whip or hand to signal that they were slowing or stopping.

An amusing story concerns Frank T. Heffelfinger and George Peavy of the Peavy Experimental Grain Elevator fame. Seems they struck out on a drive when the car bucked and sputtered and died. Hefffelfinger trudged six miles to the Peavy Elevator and instructed a man with a team of horses to rescue Mr. Peavy. The horses couldn’t find him, and after 8 hours Mr. Peavy himself trudged to the elevator, covered head to toe with mud.

Entrepreneur Paul Siever opened a rental car business in Minneapolis with two new Model T Ford touring cars that he stored in T. B. Walker’s carriage house.

With the help from a campaign waged by the Minnesota Highway Improvement Association, the Minnesota legislature approved the “Babcock Amendment” to the state constitution, which initiated the state’s system of 70 trunk highways. The amendment required a vote of the populace, and the day before the election, a parade was staged in Minneapolis, complete with slogans such as “Pull Minnesota Out of the Mud!” and “Good Roads for All Loads.” The 7,000 miles of highway were intended to connect all county seats and cities in the state. Under this plan, many state and federal highways were moved to new locations. By now there were 324,166 motor vehicles registered in the state. Automobiles were here to stay.

Pneumatic tires made for a gentler ride, but made one vulnerable to flat tires.

Sometime between 1920 and 1922 the yellow light was added to red and green on electric traffic lights, starting in Detroit and New York City.

In 1920 the nation had 8 million automobiles, a figure that was 300 % more than in 1915. Minnesotans owned approximately 300,000 automobiles.

1921

St. Louis Park had no car dealers so many residents bought Fords from Dahlberg Brothers Ford at 1028/1023 Excelsior Ave., Hopkins. On February 1, 1921, Oscar Dahlberg, Hilmer Olson, and John Schwister took over the Ford agency from Harry Leathers, who had had a car probably in the oughts. In 1953, Ward F. Dahlberg was the Business Manager, and Earl A. Dahlberg was the General Manager. At one time, Hopkins was called the car capital of the area, since it had three major car dealers.

Legislation was passed in 1921 to make the highway plan authorized by the Babcock Amendment of 1920 possible. This legislation required the commissioner of highways to carry out the provisions of the trunk highway amendment. The mandate for the Department was to acquire right of way, locate, construct, reconstruct, improve and maintain the trunk highways, let necessary contracts, buy needed material and equipment, and expend necessary funds. The same legislation authorized the commissioner to appoint two assistant commissioners, one of whom was to be an experienced highway engineer. The commissioner was also authorized to employ skilled and unskilled employees as needed.

AUTO WASH BOWL

The auto wash bowl was patented in 1921 by inventor CP Bohland, who opened two branches in St. Paul. He invented the bowl as an easy way to remove mud from the bottom of cars.

The auto wash bowl pictured below was located on the SE corner of Minnesota and Tenth Streets in St. Paul, at 82 East Tenth Street.

There were 332,625 registered vehicles in Minnesota in 1921.

The first drive-in restaurant, Royce Hailey’s Pig Stand, opened in Dallas in 1921. A precursor was a Memphis joint that provided service to cars parked in the lot.

The 1921 Federal-Aid Highway Act first created the notion of a national highway system.

1922

On March 2, 1922, the St. Louis Park Village Council passed an ordinance “to regulate the operation and use of vehicles on the streets, avenues, alleys and public places of the Village of St. Louis Park and the maximum weight, width, height and length of such vehicles.”

Minnesota’s 150 tourist campgrounds served 500,000 tourists that summer. There was concern about the safety of the drinking water and cleanliness of the camps.

An early police car, dubbed the “Bandit Chaser,” was put into action in Denver. It featured a Cadillac engine and a machine gun on the hood.

Ford bought the Lincoln Motor Company. Half the cars on the road, in America and Europe, were Model Ts.

The first back-up lights were introduced, on the Wills-St. Clair.

The Minnesota Highway Department was established, with quarters in the basement of the State Capitol.

1923

On September 6, 1923, an ordinance was passed to protect life and prevent damage to persons and property..” It prohibited the use of any machine, auto, or other mechanical appliance as to endanger his own life or limb or the life or limb of others. Fines ran from $5 – $100 or 5-90 days in the county jail.

Minnesota banned billboards and advertising along its trunk highways.

1924

An ordinance passed on July 18 limited the speed of automobiles on Excelsior Blvd. and Minnetonka Blvd.

Radios first appeared in cars, but only became commonly available in the 1934 Ford. By 1948 they were standard in most cars.

John and Horace Dodge assembled 1,000 per day until they were bought out by Walter P. Chrysler in 1928.

A Ford automobile set you back $920.

1925

The Minnesota Department of Highways was formed.

James Vail opened the first “motel” in San Luis Obsispo, California. The term was picked up, but in the early days, it might mean a crudely-built four room building. A room was furnished with a pot-bellied stove, and in the winter snow might blow in the cracks.

Hertz offered the first rental car company, called the “Drivurself.” In 1926 there was a franchise at 3 South 8th Street in Minneapolis.

Walter P. Chrysler established the Chrysler Corporation.

1926

The Oakland Automobile Co. introduced the first Pontiac.

The American Association of State Highway Officials established and numbered interstate routes, selecting the best roads in each state to become part of the network. Use of colored markers to identify roads made its way out.

An article in the Dearborn Independent decried “Messy Motorists Mar the Landscape: Unmannerly Tourists Tear Down Trees and Outrage the Canons of Cleanliness.” Some excerpts:

Nothing could come much closer to the ideal method of enjoying a brief breathing spell from the cares of business or household routine than to pile the family into the car and hie forth for a joyous picnic in the country.

But some of the “75 or 80 million people who go out auto picnicking or take to the broad highways with their camping trailers, tents, pots, pans, mosquito lotions, and other gypsying paraphernalia” were making a mess of the countryside.

They tear down fences and valuable trees for firewood, steal vegetables, flowers, fruit and sometimes chickens, eggs, and milk on the hoof, as it were; pollute wells, ponds, and springs by washing dishes and clothes in tem; go swimming in scanty costumes in too close proximity to highways and habitations; violate game and fishing laws; and in other ways give evidence of their total irresponsibility and barbarity.

In addition to their sloppy ways, Sunday drivers were aggravating in other ways:

Another close relation is the road hot, the blighter who drifts along at a leisurely pace until you want to pass him. Then he spurts and does what he can to crowd you into a ditch. Or, perhaps, he is unwilling to keep his place in the line of vehicles and tries to pass everything on the road, regardless of sense or safety. This fellow has so many disagreeable traits that a weighty encyclopedia would not hold the descriptions of all of them.

Some things never change. In 1926 this behavior was attributed to an inferiority complex.

1927

A “Rumpus” occurred at the Hennepin County Fair when E.D. Tourangeau, who supplied an automobile to be awarded as a prize, was arrested for selling dance (raffle) tickets without proper authority. The complaint was withdrawn, as was the car from the prize list, with the result that thousands of people who had bought tickets trying to win the vehicle were “hostile against those in immediate charge of the fair and are threatening suits for recovery of their money.” (Hennepin County Enterprise, September 1, 1927)

Ford replaced the “tin lizzie” with the bigger and more comfortable Model A, but Chevy outsold Ford for the first time.

Curbside mailboxes were first installed in Houston.

1928

The Chrysler Corporation sold Dodges, DeSotos, Plymouths, and Chryslers.

There were over 1.48 million registered vehicles in Minnesota.

1929

Metal signs with route numbers marked inside a star were introduced. Previously roads were identified by numbers stenciled on utility poles and other methods of marking.

Ford created the first mass-produced station wagon, a 1929 Model A. The first production station wagon, William Durant’s Star Station Wagon, debuted in 1923.

The Held family of Golden Valley (and St. Louis Park) operated the first gas station west of Minneapolis.

1930

The State began to require tourist camps to provide clean facilities and drinking water, and to reduce fire hazards.

Howard Buster Johnson opened a restaurant outside of Boston, the first of hundreds of Howard Johnsons nationwide.

L.V. Dowling protested against the proposed erection and operation of a Tourist Camp on Excelsior and Highland [36th] and Fern [Lynn]. Somehow that doesn’t add up.

State and Federal agencies took over the development of highways and private associations began to fall by the wayside.

1931

The Minnesota Bureau of Tourism was formed as a division of the Department of Conservation.

The “School Police” was established in St. Louis Park. The Automobile Club of Minneapolis began providing belts and badges to schools in Hennepin County in 1928.

West Virginia passed a law that made it unlawful for anybody to drive so slowly as to impede or block the normal movement of traffic.

1932

The Roadside Development Division was formed as a division of the Minnesota Department of Highways. See the chapter on Highway 100’s Roadside Parks. Ford replaced the Model A with the first V-8.

From November 15-21, the Minneapolis Junior Association of Commerce hosted a Six-Day Bicycle Race at the Minneapolis Auditorium.

1933

The first drive-in theater opened in Camden, New Jersey on June 6. The field was large enough to hold 500 cars, and the screen measured 40 x 50 ft. At their peak, there were over 4,000 drive-ins across the country.

During the Depression, the Federal government funded road construction to the tune of over $1.8 billion, putting millions of unemployed men to work.

Decent roadside accommodations were still few and far between, and travelers relied on “tourist homes.” People put up signs in their front yards, and were paid $1.50 to $2.50 per night for a room in their house for the night.

1934

With the opening of Highway 7 in November, George Seirup established Park’s first automobile dealership, a sub-dealer for Dahlberg Ford – on Wooddale Avenue. George constructed a showroom and garage and received $25 from Dahlberg for each car sold. This was the only automobile dealership in the Park until after WWII. In the ’30s, Fords were available for $25 down and $25 a month.

A cars was expensive. It had to be greased every 1,000 miles; got less than 15 miles per gallon; new tires were worn out after 20,000 miles; gas was five gallons for $1. All this on a living wage of 50 cents an hour.

On May 4, 1934, the state highways were renumbered in less than one day. Old maps will show Highway 7 as 12, etc., before the change.

The Volkswagen Beetle was begun when Adolph Hitler ordered Dr. Ferdinand Porsche to develop a small car “for the folks.” Porsche had been trying to find interest in his small car, and although he was not a Nazi, he took up the challenge.

1935

Cities discovered the money that could be made from parking meters. Oklahoma City was the first to use them, on July 16, 1935.

1936

Highway Chief McDonald toured Germany and admired the Reich Autobahn, built by Dr. Fritz Todt. During the war, General Eisenhower would observe that it was easier to disrupt train traffic than road traffic, making the interstate highway system a national security concern.

1937

St. Louis Park passed bicycle ordinance No. 117 on June 16, 1937.

1938

Buick introduced turn signals.

The Volkswagen Beetle (so-named by an American reporter) was put into production at a factory in Wolfsburg – a town created for the workers at the factory. Production soon turned to military vehicles, including the German version of the jeep.

Bicycle licenses were required for the first time. Earl Ames donated his metal license:

1939

30.7 million cars were registered nationwide – one for every four people.

1940

The St. Louis Park Village Council passed a Taxi ordinance.

Highway 55/Olson Memorial Highway, the former Sixth Ave. North, opened in October 1940.

1942

On January 2,1942, Washington halted the sale of all passenger cars and trucks while a rationing system was implemented. This action froze over 2,000 new cars in the Minneapolis area. Production of all domestic vehicles was suspended on January 30 for the duration of the war, as car companies retooled to produce planes, tanks, etc.

Tires were so scarce that motorists were urged to register their tires at gas stations in case of theft.

1943

The speed limit on State trunk highways in Minnesota (that included Highway 100) was 35 mph.

1944

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944 provided states with funding to improve secondary rural and urban roads. Minnesota’s State Aid Division was created in 1945 to carry out this activity.

1945

St. Louis Park had one traffic death in 1945, the first in three years. It had been expected that the end of wartime speed restrictions would cause more fatalities, but this was not borne out locally.

In the 1940s and ’50s, the place to go in St. Louis Park for your drivers license was to Lydia Rogers. The fee was 50 cents and there was no test.

After the war, the British command restarted production of the VW Beetle, and it became popular in Europe.

1946

Wartime speed limits were raised.

1947

In September, Roy Whipps requested that stop signs be placed on Wooddale between Excelsior Blvd. and 44th Street.

In November 1947, stop and go signals were authorized for the intersections of Ottawa and Minnetonka, and Brookside and Excelsior.

Radar, developed by Hamline graduate Dr. Robert M. Page in 1935, was first used to catch speeders. It was still new in 1955, as evidenced by song of the same name by Mr. Bear and His Bearcats.

1948

The St. Louis Park Village Council passed a parking ordinance.

Inspired by the P-38 “lightning” fighter plane, Harley Earl at GM placed the prototype of what became gigantic tailfins on the 1948 Cadillac. Tailfins reached their peak around 1959-60, “the year when the Cadillac Eldorado convertible took on the appearance of the Batmobile.” One theory was that tailfins were supposed to stabilize motion as the car reached 70 mph.

1950

As with Highways 100 and 7, in 1950 the Village signed contracts with the State promising to allow no curb gas pumps, gas stations, or billboards on Highways 7, 12, and 100.

VW started production of the VW Bus, officially called the Transporter.

1951

Advertising in a May issue of the local TV Times was the New Brighton Race Track. SUNDAYS, Hot Rod Races, the ad thundered. They were televised by WTCN at 2:30, on what was then Channel 4.

1952

John Yngve, Deputy Registrar, Motor Vehicle Registration Bureau, issued 13,500 license plates in 1952.

St. Louis Park passed bicycle ordinance 404 n October 27, 1952, replacing the ordinance passed in 1937.

Charles Kemmons Wilson opened his first Holiday Inn, named after the movie, on a road leading into (or out of) Memphis.

1953

The Government lifted production restrictions required for the Korean War, and car culture went into overdrive.

Cadillac introduced air conditioning.

Anderson Cadillac opened, located at 5100 Excelsior Blvd., across from Miracle Mile. This was the site of the Waddel farm, owned in the 1920’s by C.B. Waddel, a Hennepin County Commissioner and likely descendant of Sarah E. Waddel, who owned a strip of land along Excelsior Blvd. that ran all the way to 36th Street according to an 1889 map. The firm paid $14,000 for the house. The dealership, headed by Victor E. Anderson of St. Paul, was apparently a spinoff of Warren Cadillac. The building was designed by architects Lang & Raugland. Its 16,000 square feet occupied four acres, and featured a glass enclosed showroom. Victor Anderson was a former director of the Minnesota Automobile Dealers Association. Reuben L. Anderson, Vice President of the new Dealership, was a plumbing and heating contractor, and was said to have held the contract for remodeling the White House in Washington. In 1956, a second story was added to the structure to house Anderson-Cherne contracting co. At the time, Anderson Cadillac was only the second Cadillac dealer in Hennepin County. In 1965, Anderson Cadillac moved to 7400 Wayzata Blvd.; in 1966 the site was briefly the home of Riviera Imports.

There was a cab stand on Wooddale outside Snyder’s.

1954

At his confirmation hearing to be appointed Secretary Defense, Charles “Engine Charlie” Wilson, the President of GM, was (mis)quoted as saying “What’s good for General Motors is good for the nation.” He actually said it the other way around, “and vice versa.” The press had a field day.

The Nash Kelvinator Corp. merged with the Hudson Motor Car Co. to become the American Motors Corporation.

The state’s name was added to road signs.

The police car of choice in the U.S. was the 1954 Ford Interceptor.

Two pedestrians were killed during the year, including one inebriated St. Paulite who was killed crossing Excelsior Blvd. near Ottawa, outside the lines. 104 people were injured in traffic during the year.

1955

Traffic accidents were up 40 percent in St. Louis Park. There were 100 more accidents in 1955 than in 1954.

City limit signs were installed on Highway 7.

It was a different time. City employees were told not to keep their cars idling while they were inside having a coffee break.

The City erected or allowed signs to the tiny Christian Science Church on Brookside Ave. to be erected at Excelsior and Brookside, Hwy 100 and Vermont, and Brookside and Yosemite.

1956

Standard street name signs were ordered by the City Council – Scotchlite was specified. Earl Anderson had been providing new street signs for the last four years. At the time there were about 400 street signs.

As of January 1, some 140 miles of roads in Hennepin County were turned back to their various communities for maintenance, including Highway 18.

An 18-year old Dean Frietag hitchhiked to St. Paul and got hired by the State Highway Department. His Geometrics unit (dubbed the “Dream Boys”) worked out layouts and designed interchanges, including those on Highway 100. At the time, there was just Minneapolis, St. Paul, and 13 suburbs. He says the Highway Dept. had all sorts of ideas, including turning Highway 7 and Excelsior Blvd. into freeways, but there was too much local opposition.

In 1956, the voters of Minnesota approved a constitutional amendment to provide for the orderly distribution of state road user funds. The percentages established were 62 percent state, 29 percent county, and 9 percent municipal.

The Interstate Highway System was officially created with President Eisenhower’s signing of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. The law provided $25 billion over 12 years, created the Highway Trust Fund, and required that the highways accommodate projected traffic levels of 1972, which is the year the system was to be completed. The first 8 miles were opened outside of Topeka, Kansas on November 14. In 1991, Congress officially dubbed the system the Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways.

Interstate 694 was authorized in 1956. The first section was completed was between U.S. 10 at Arden Hills to I-35E at Little Canada in the early 1960s. The last section of I-694 completed was between I-35E at Little Canada to its junction with I-94 / I-494 at Oakdale / Woodbury, completed by the early 1970s. Interstate 694 was built as the main thoroughfare for the northern suburbs of Minneapolis – Saint Paul. These include the cities of Maple Grove, Brooklyn Park, Brooklyn Center, Fridley, New Brighton, Arden Hills, Shoreview, Little Canada, Vadnais Heights, White Bear Lake, Maplewood, Pine Springs, and Oakdale.

Interstate 94 in Minnesota was authorized as part of the original interstate network in 1956. It was mostly constructed in the 1960s.

I-94 follows the original route of old U.S. Highway 52 from Moorhead to St. Cloud, then I-94 stays south of the Mississippi River along the former route of old State Highway 152 between St. Cloud and the Twin Cities. I-94 then passes through both downtowns and exits toward Wisconsin along the former route of old U.S. Highway 12.

The first section of I-94 in Minnesota constructed was between Moorhead and Albany in the early 1960s.

The section of I-94 between Minneapolis and Saint Paul was completed in 1964.

The section of I-94 between St. Paul to Hennepin/Lyndale Intersection was completed in December 1968.

The section of I-94 between Maple Grove and Brooklyn Center was completed in 1969.

The Lowry Hill Tunnel was completed in December 1971.

The section of I-94 between Saint Augusta and Maple Grove was completed in 1973.

The section of I-94 between Albany and Saint Augusta was completed in 1977.

The section of I-94 between the Lowry Hill Tunnel to Dowling Ave. No. was completed in November 1981. Governor Al Quie rode a 1914 Model T the 3.5 miles to open the stretch.

The section of I-94 between Dowling Ave. N. to I-694 was completed in November 1983.

The section of I-94 from Brooklyn Center through north Minneapolis was completed in 1984.

The last section of I-94 in Minnesota constructed was the ten miles (16 km) between its junction with I-494 / I-694 at Woodbury and the Wisconsin state line at Lakeland. This was completed in 1985.

Seat belts were made available for the first time in selected Ford automobiles. The optional “Lifeguard” safety package cost about $27. Doctors had started to install seat belts in their own cars after seeing the deadly head injuries suffered by car crash victims.

1958

Could this be right? No traffic deaths were reported in St. Louis Park in 1958.

Congress passed a bill creating a “National System of Interstate and Defense Highways.” The law included provisions for the taking of private property, required public hearings, and called for consultation with the Federal Civil Defense Administrator and the branches of the Military. Emphasis was placed on the civil defense angle: “the ‘Interstate System’ is essential to the national interest and is one of the most important objectives of this Act.”

Roads leading out of cities would facilitate evacuation in the case of nuclear attack. Also, the road had to be wide enough to handle tanks being hauled on the back of flatbed trucks. Highway bridges were built at 16′ 4″, the height of mobile rockets. The Interstate System was restricted to 41,000 miles, and was required to be “adequate to accommodate the types and volumes of traffic forecast for the year 1975.” One mile in every five must be straight. These straight sections are usable as airstrips in times of war or other emergencies. The U.S. Bureau of Public Roads was designated under the Commerce Department, headed by the Federal Highway Administrator.

The Automobile Country Club was closed.

The first stretch of I-35 was 8 miles between Owatonna and Medford.

1959

In February 1959, Mr. E.J. McCubrey of the State Highway Department appeared before the City Council to discuss plans for Highway 12. Council notes indicate that adjacent landowners wanted a “peel off lane” or cut off from 12 to the north. McCubrey indicated that such a plan would probably not be approved by the Bureau of Good Roads.

35-W Joins the Nation! On August 17, 1959, at 10:00 am, Dedication Ceremonies were held to open Highway 35 W in Bloomington (at 86th Street). The program was arranged by the Special Events Department of the Minneapolis Area Chamber of Commerce, and the president of that body, E. William Boyer, presided over the ceremony. Minnesota Governor Orville L. Freeman was the Dedication Speaker, Commissioner of Highways L.P. Zimmerman made remarks, and Distinguished Guests were the Mayors of Bloomington (Gordon W. Miklethun), Richfield (Irving Keldsen), and Minneapolis (P. Kenneth Peterson). The banner was broken by Torchy Peden, listed on the program as the Former World Bicycle Road-Racing Champion. Music was provided by the Bloomington City Band, directed by Robert Shannon.

1960

718 people were killed in traffic accidents in Minnesota.

1961

Wisconsin and New York became the first states that mandated the use of seat belts in the front seat.

1962

I-35 was dedicated near Hinckley in the fall.

The Highway Department proposed “Southwest Diagonal.” The road, later abandoned under a flood of protest led by the Chamber of Commerce, was originally intended to go from downtown Minneapolis to the new town of Jonathan.

“The proposed route… would take Highway 169 on a winding course from a point just north of Excelsior Blvd. on Highway 100, northeast through a major industrial zone [through the site of the Rec Center], across Highway 7 and Lake St. near Chowen Ave., then east of Cedar Lake to a junction with Highway 12 near Penn Ave. Plans call for the rerouting of Highway 7…[which] would mean a probably large but presently undetermined number of homes in Minneapolis would be condemned to make room for the highways.”

In January 1962, the Star reported that Park refused to agree with the plan, and the Highway Department held up work on upgrading the deadly Excelsior Blvd/Highway 100 intersection. Mayor Wolfe appealed directly to the Governor for relief. In the meantime, only a stoplight regulated traffic at this busy intersection. One businessman suggested erecting a sign at the site: “This congestion due to the courtesy of the Minnesota Highway Department.”

In October 1962, the Highway Department relented and approved plans for an upgraded interchange at Highway 100 and Excelsior Blvd. The State approved a modified diamond-cloverleaf interchange, where 60,000 cars traveled each day. City Fathers were reportedly “jubilant” at the news.

1963

Volvo was the first manufacturer to install shoulder belts as well as lap seat belts as standard equipment in their cars. The other manufacturers followed suit the following year.

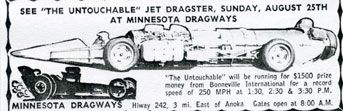

In August our local TV Times advertised Minnesota Dragways, on Highway 242, 3 miles east of Anoka.

Hennepin County/Minnesota Highway 62 opened from France Ave. to I-35W.

1964

I-94 opened between Minneapolis and St. Paul. Coincidentally, the first Skyway opened in downtown Minneapolis. The route roughly followed an old stagecoach trail and was originally planned to go through the U of M but that was kiboshed. It did decimate the Rondo neighborhood, which was primarily African-American. The diagonal nature of it (from the Cities to Fargo) also bisected many farms and infuriated many farmers. Usually, highways were at square corners, following property lines. 94 today runs from Billings, Montana to Detroit – a rare Interstate that does not go coast to coast.

1965

At the behest of his wife, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Federal Highway Beautification Act, which required billboards to be at least 600 feet from the highway and junkyards to be camouflaged.

Ralph Nader wrote Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-in Dangers of the American Automobile.

Hennepin County/Minnesota Highway 62 opened between future I-35W to Minnesota 55/Hiawatha Ave.

1967

Highway 35W from Highway 62 to 31st Street was opened in January 1967. It was extended from 31st Street to Downtown that November.

1968

The first child safety seats were sold by Ford and General Motors. The first Federal seatbelt law was passed, requiring the driver and all passengers in the front seat to buckle up.

I-94 was connected to I-35W just south of downtown Minneapolis.

1969

Minnesota created the Department of Public Safety, which took over the Highway Patrol and Drivers License Bureau from the Highway Department.

State highway signs were changed from black and white to blue and gold.

1970

Minnesota had 2,201,000 registered vehicles on the road.

The 1970 revision to the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways made major changes to many street signs, including changing the yellow Yield sign to red, and instituting those triangular No Passing Zone signs.

Phillips Petroleum moved out of Minnesota.

1971

VW Beetles reached their peak production, with 1.2 million.

1972

Right Turn on Red came into being in the Park on July 1. It had been enacted by the State in 1965, and intersections had to be posted.

All passenger cars were required to include front shoulder and lap belts, and that annoying buzzer that reminds you to buckle up. The modern dual belt with both shoulder and lap belt on the same buckle, became standard in 1973.

The number of bicycles worldwide was said to be 50 million. In St. Louis Park, over 1,547 bicycle licenses were sold. There were only a few designated bike trails in or around Park.

1973

I-35W from I-94 to University Ave. was opened in June 1973. It was extended from University to E. Hennepin that September.

1974

1975

I-35W was opened between E. Hennepin to State Highway 36 on November 13, 1975.

1976

AAA Minneapolis moved to its current location in St. Louis Park, on top of the former garbage dump. Its original headquarters was in the Radisson Hotel and later the Plaza Hotel in downtown Minneapolis. In 1922 it was moved to a townhouse at 13th and LaSalle. In the 50’s, the townhouse was demolished and the operation moved to a remodeled auto agency next door. That, in turn, was overtaken by the Loring-Nicollet redevelopment, which resulted in the move to Auto Club Way in the Park.

MnDOT, or the Minnesota Department of Transportation, was created in 1976 by the Legislature (Minn. Stat. Ch. 174) to assume the activities of the former Departments of Aeronautics and of Highways and the transportation-related sections of the State Planning Agency and of the Public Service Department. Today MnDOT develops and implements policies, plans and programs for aeronautics, highways, motor carriers, ports, public transit and railroads.

1978

The last VW Beetle was produced in Emden, Germany. It continued to be produced in South America until the late 1990’s.

1985

Work was completed on I-494. Some members of the Highway Department had wanted the highway to reach to 106th Street on the south, but 78th was chosen as it was doubted that anyone would ever live that far out.

1986

494/694 was opened in November 1986.

On July 16, 1986, the Flintmobile came to town, part of a nationwide tour to educate children to buckle up. Fred Flintstone came to Peter Hobart Playground and was also available for viewing at AAA Headquarters. The event was sponsored by AAA.

1988

Effective July 1, 1988, County Road 18 became Highway 169.

1993

Only 2 of 103 auto clubs remain in operation: AAA Minneapolis in St. Louis Park, serving Hennepin County, and AAA Minnesota, based in Burnsville, serving the rest of the state.

1997

The Cedar Lake LRT Regional Trail is the trail that parallels Highway 7 through St. Louis Park. The portion of the trail that runs from Hopkins east to Beltline Blvd. was built in 1997. The trail section that runs from Beltline Blvd. east to where it connects with the Midtown Greenway was completed in 2001.

2000

The North Cedar Lake Regional Trail was completed in 2000.