Despite the fact that St. Louis Park was founded by straight-laced New Englanders, liquor has played a part in the history of the City. Also see Steel Toe Brewing, Early Ordinances , Drugs in the Park, and Smokin’ in the Boy’s Room.

The first saloon in Minnesota was established in the 1830s by Pig’s Eye Parrant in a cave in St. Paul.

The first temperance society sprung up in 1848.

Minnesota had an early prohibition law in 1852, but the abolitionist movement moved to center stage and the law was repealed.

Liquor taxes were essential to pay for the cost of the Civil War. Many Civil War veterans came home with morphine addictions.

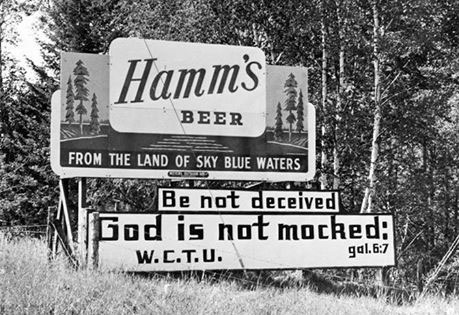

The National Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was formed in 1874 in Cleveland.

1883

For a city that at one time was known for its strip of bars, it’s ironic that the settlers of St. Louis Park were of a different bent. An 1883 biographical sketch paints pioneer Daniel J. Falvey as an “outspoken advocate of temperance who had done all he can to sustain the village against any intrusion of the liquor traffic.”

The Prohibition Party of Hennepin County had their convention on September 26, 1883, convened by chairman J.B. Stevens. Delegates from Minneapolis Township (which included the area that would become St. Louis Park) were Melvin Grimes and George S. Grimes. The Resolutions are worth repeating, as reported by the Minneapolis Tribune:

- The prohibitionists of Hennepin county in convention assembled do hereby declare their allegiance to the Prohibition Home Protection party of this state and nation, and hereby pledge this party our hearty support.

- We are as ever fully convinced that nothing short of the entire prohibition of the liquor traffic as a beverage will remedy the great evils of intemperance, and we therefore again declare ourselves opposed to any license regulation, knowing it to be an utter failure in suppressing these evils.

- That high license as a policy in relation to this traffic has proven itself a delusion and a snare [?] and has nothing whatever in it to benefit the cause of temperance or the interest of the country at large; and we do hereby discard it as one of the false compromises which the enemy is over throwing in the way of prohibition and national progress.

- Believing that prohibition as a political principle demands the efficient aid of a political party, we do, therefore, by our meeting together today and the nomination of a ticket, place ourselves right before the people on this question.

1890

The Hennepin County Prohibition Party had its convention at the Labor Temple on June 13, 1890. They elected a new county committee and appointed delegates to the state Prohibition Convention which convened on June 24. George F. Whitcomb was elected president. Most of the delegates were from Minneapolis; Frank Reidhead was the delegate from St. Louis Park.

1891

A cautionary tale was the story of Louis Retwat, a Norwegian laborer who was killed by a Hastings and Dakota freight train near Lake Calhoun in April 1891. Although the engineer did everything to warn him and stop the train, Retwat made no movement until the train was within a few feet away. He had been working in St. Louis Park grading but he quit and took to drinking; “A bottle containing a few drops of alcohol explained his seeming indifference to the approach of the train…”

1892

On January 6, 1892, St. Louis Park Boarding House keeper Engelbert Kommers plead guilty to selling liquor without a license and was sentenced to a $50, court costs, and 30 days in the county jail. “After paying his fine Kommers quietly walked out of the court room. His absence was not discovered for a few minutes, when a deputy sheriff started hastily in pursuit to enforce the 330 days’ part of the sentence. He gave himself up at the sheriff’s office. Application will be made to the governor for a pardon.”

On February 5, 1892, the Village Council passed Ordinance No. 15 requiring a license in order to “sell, barter, give away or otherwise dispose of spirituous, vinous, fermented, malt, or intoxicating liquor.” The ordinance did not apply to druggists or licensed pharmacists.

1893 – Dry

The (National) Anti-Saloon League was established in 1893. Its prime legal advisor and lobbyist Wayne Wheeler would become the prime architect of Prohibition. The Non-Partisan Women’s Christian Temperance Union of St. Louis Park held a mass meeting in the Methodist Church just before the March vote.

Although liquor was illegal in St. Louis Park, so-called “blind pigs” were ubiquitous.

Wikipedia on the concept of the Blind Pig:

The term “blind pig” (or “blind tiger”) originated in the United States in the 19th century; it was applied to lower-class establishments that sold alcoholic beverages illegally. The operator of an establishment (such as a saloon or bar) would charge customers to see an attraction (such as an animal) and then serve a “complimentary” alcoholic beverage, thus circumventing the law.

A speakeasy was usually a higher-class establishment that offered food and entertainment. In large cities, some speakeasies even required a coat and tie for men, and evening dress for women. A blind pig was usually a dive where only beer and liquor were offered.

Another explanation of the term “Blind Pig” is that the police were bribed into looking the other way, making for a “blind pig.”

In his history of St. Louis Park, Norman Thomas wrote: “One hotel reportedly had a room into which thirsty persons could retire and satisfy their tongues. It gave keys to the customers and only those with the pass key could get in. One pioneer said that ‘nearly everyone in town had a key.'”

On February 18, 1893, seven ladies from the Central Non-Partisan WCTU traveled to St. Louis Park to speak and create a chapter there. They met at the Methodist Church and were addressed by state president Mrs. P.B. Walker. Judging by how the Minneapolis Tribune article massacred most of the names, this may well be Mrs. T.B. Walker. Mayor Hamilton and Rev. Kerfoot of the Methodist Church also spoke. Seventeen Park women organized, led by Mrs. J.W. Ferner (probably Werner). The article ended thus:

St. Louis Park, being a manufacturing suburb, is considered a point of very great interest and importance by temperance workers, and the ladies feel that their day has been well spent in planting there a little seed of righteousness and truth, which they trust may grow into a might tree, “whose leaves shall be for the healing of the people.”

For the first time, the Village of St. Louis Park put the matter of allowing liquor licenses to a vote in 1893. These votes were held every March until national Prohibition was enacted in 1919. Before this first vote the Minneapolis Tribune printed an extensive report on the situation and the politics involved in the Park.

The Minnesota Liquor Dealers’ Association or some of their agents have laid siege to the new manufacturing suburb. In several of the boarding houses there are men whole sole business seems to be to talk and make sentiment for the liquor cause. There is no end of the “good hot stuff” to be had, if you only know who to strike for it, and there is talk that when the campaign opens in earnest there will be money enough and to spare.

The fight against liquor began two years ago. It centered pretty largely in the prosecution of [Engelbert] Kommers, a German boarding house keeper, who was charged with keeping a blind pig in his hostelry…. President Hamilton, of the village council, says:

“He has been arrested several times and once was convicted and sentenced to 90 days in jail besides fined. He pleaded so hard, with tears in his eyes, if the court would be lenient he would quit the business, that Judge Lothren joined with County Attorney Thian in recommending a pardon, which was granted by Gov. Merriam.

“Subsequent to this conviction Kommers was convicted before a justice of the peace of St. Louis Park and fined $100 and the case was appealed to the district court, where it now awaits action. He was again arrested and tried twice, the jury failing to agree both times. The third trial the case was dismissed.”

The agent of the Milwaukee Bottling Company was arrested several times on the streets of the village and convicted for selling liquor contrary to the village ordinance. All these pestiferous prosecutions have made the liquor men hot. St. Louis Park being a new and rapidly growing town, the temptation was great to the liquor men. The claim is made that there were three or four blind pigs constantly dispensing liquid refreshments.

Although there were plenty of dry candidates for Village office, only Mr. Kommers was willing to run on the wet ticket. He was really interested in being Village Council President but he knew the makeup of the council would have an effect on if liquor licenses were approved. When asked to describe his platform, he said:

I ain’t got anything against women and preachers, but I want the preachers to tend to their churches and the women to stay in their homes and let the men do the rest. I don’t believe we should be dictate to by a lot of women whether we should have saloons or not. I’d like to know which is the worse: Now my boarders to up town on Saturday and a lot of them bring bottles and jugs with them, so Sunday all day there are a lot of drunken men around. Now, if we had the whisky right in the house the men would not need to buy it by the bottle but they could get just what they wanted by the drink.

In the end the Village voted dry by a vote of 213 to 103. [140 to 102 according to the St. Louis Park Mail] A few days later the Minneapolis Tribune reported:

T.B. Walker is extremely gratified with the result of the election, and yesterday, while speaking of the matter, said:

“The defeat of license at St. Louis Park is a grand thing and will be the foundation of numberless improvements in the way of new buildings and factories. It will add much to the prosperity of the park, and will encourage the best classes of people to come and erect residences there.

“The election was carried largely by the employees of the factories, and party had nothing to do with it. Of those elected to office I have no idea of their politics, whether they be Republicans or Democrats. We were out to down the saloon business in the place, and we did it.

“Now that the election has gone right,” continued Mr. Walker, “I will give out a few facts in regard to the buildings that are to be erected.”

Walker then outlined his plans to erect numerous houses, hotels, a bank, city hall, library, schools, even water mains. All of this apparently hinged on the village voting dry.

But Engelbert Kommers was again charged with selling liquor without a license at St. Louis Park in April.

The Annual Catalogue of the St. Louis Park Public Schools for 1893-4 describes the various schools, boasts that the village has seven factories and three churches, and “no saloon or den of vice.”

1894 – Dry

Polling numbers were inconsistently reported in 1894:

- 186 against issuing liquor licenses and 130 for, a spread of 56

- The Tribune reported a spread of 50 votes.

- The St. Louis Park Mail reported 195 against license, 130 for, with a spread of 65.

The Mail also reported the rumor that T.B. Walker threatened to close all his factories of the village went wet. This made the factory men mad – they did not appreciate having a threat over their heads. The Mail speculated that, had the story gotten out sooner, the wets would have won, although there was no evidence that Walker ever made the statement. The WCTU ladies of the Park showed their appreciation for the vote by holding a ratification meeting at “school house hall,” promising speeches, music, and a free supper.

D.W. Bath, the publisher of the Mail, despite his name was a “dry,” and apparently took shots at those who loved their liquor. One story, only identified in reprint as taking place in the 1890s, was:

Milkman Holter packed his skin full of Minneapolis bug juice last Wednesday and proceeded to his home near this village where he at once began making things interesting for his wife and children drivinig them out into the snow with a butcher knife.

Complaint was made to Justice Torkelson, who ordered Holter’s arrest and Constable Kelfield went out and brought the festive milkman in and give him elegant quarters for the night in the hotel-de-jug.

In the morning the justice placed him under $300 bonds to keep the peace. Holter is all right when he lets whiskey alone and the experience of the past few months ought to teach him that he can’t drink whiskey and be a man.

1895 – Dry

St. Louis Park stayed dry in 1895, voting 216 against license and 56 for.

1897 – Dry

In the 1897 election the Village voted dry by a vote of 87 to 61. The vote was preceded by a “No License Meeting” at the Oddfellows Hall featuring an address by George F. Wells of St. Paul.

1898

A poolhall ordinance was passed on June 26, 1898:

- Poolroom operators had to give the Village a $200 deposit

- Poolhalls had to close at midnight and all day on Sunday

- Pool rooms must not become a public nuisance by reason of boisterous or profane language or unseemly behavior or actions by its patrons.

- The fee for each pool or billiard table is $5 per year

1899

In 1899 lunatic Carry Nation carried out her first hatchet job in a Medicine Lodge, Kansas, drug store that was illegally selling liquor. After several raids in Kansas, she branched out to other cities, including New York. She became a media sensation – songs were written about her and her name is known to this day. She died in a mental institution at age 65.

1902 – Wet

St. Louis Park went wet after a vote on March 11, 1902, with 135 for “license” and 73 against. A new liquor ordinance was passed on April 4, 1902, regulating spirituous, malt fermented, vinous, or mixed intoxicating liquors. On May 1, Conrad Birkhofer of Minneapolis received the first license to sell intoxicating liquor. Several other men applied for licenses as well, although the fee was $1,000. The town drunk was so boisterous that the Village Council felt compelled to pass a ruling that he be arrested every time he caused a disturbance.

1903 – Wet

Another vote was taken on March 10, 1903, with 96 for license and 30 against. On May 1, Birkhofer renewed his license for $1,000. In July 1903, mention was made of Fred Wallin’s Saloon on Grant Street, now Brunswick. In fact, Wallin was fined $100 by Justice A.H. Wood, but the Village Council refunded the fine, saying the proceedings were not legal. This may actually be Fred Whalen, as that is an old St. Louis Park name.

1904 – Wet

It is unclear whether there was a vote in 1904, but in April two licenses were granted, at $600 apiece, to J.S. Williams and August Ohde. This apparently didn’t go over too well with Birkhofer, who appeared before the Village Council on May 6 to discuss his license. A 15 minute recess had to be called to give Mr. Ohde and Mr. Birkhofer time to settle their difficulties in regard to the building now occupied by Mr. Wallin. At the end of the year, a Mr. Amos T. Morton applied for a license to run a pool table in a location next to the saloon. He paid $5 per table, and could not serve any liquor.

Also in 1904:

HELD UP A SALOON

Masked Men Get $50 at St. Louis Park Place.

Two masked highwaymen walked into Fred Whalen’s saloon, at St. Louis Park, last evening, and compelled the bartender to hand over $50 from the cash drawer. The robbers were heavily armed. From their description it is believed that they are the men who held up a groceryman at Hopkins a few weeks ago. Minneapolis officers were immediately notified. (Paper unsure; probably Minneapolis Morning Tribune)

1905 – Dry

The liquor ordinance was revised on February 3, 1905. On that same day August Ohde’s widow Minna put in a request to the Village council to transfer his license to Mr. Morton.

In March 1905 the tables turned and the Village went dry with the vote 103 for license and 132 against. Also in 1905, Minneapolis declared that no liquor could be sold within the City limits on Sunday.

1906 – Wet

The wets were in business again in 1906 with a vote of 100 dry and 115 wet. That May John Sanberg and Fred Wallin applied for licenses at $600 apiece.

1907 – Wet

On February 14, 1907, a note in a Labor News in the Minneapolis Tribune mentions a J.F. Engle as a member of the bartender’s union. Engle was a former business agent but recently went in business for himself in St. Louis Park.

In 1907 the wets won out in St. Louis Park by 22 votes. In April liquor licenses were requested by Charles H. Perry and John Sandberg, this time at $700 apiece. Then there’s this curious entry: the Recorder was requested to write the Minneapolis Light and Power Co. and also the Birkhofer Brewing Co. in regard to changing the location of the saloon on Brownlow Ave. There were two hotels on Brownlow, right across the street from T.B. Walker’s Methodist Church.

1908 – Dry

On March 5, 1908, Rev. J.M. Cleary, pastor of St. Charles Catholic Church, gave a talk at the St. Louis Park Odd Fellows Hall on “Civic Life.” It was primarily a temperance talk, in which he said that liquor traffic rudely disturbed social harmony and was an obstacle to civic peace. The Minneapolis Tribune reported:

In St. Louis Park he was happy to think the saloons had not made much progress. There they were still comparatively free from the baneful influences and degrading effects which were only too visible wherever the saloon was given absolute sway; and while he did not come out there to lecture to them or to point out to them their duties, still he hoped they would continue to realize their duties in the matter and continue to preserve for their locality that good moral atmosphere which he was glad to find there.

Reverend Cleary must have made an impression, for in the annual election the Village voted 107 for license and 139 against.

1909 – Wet

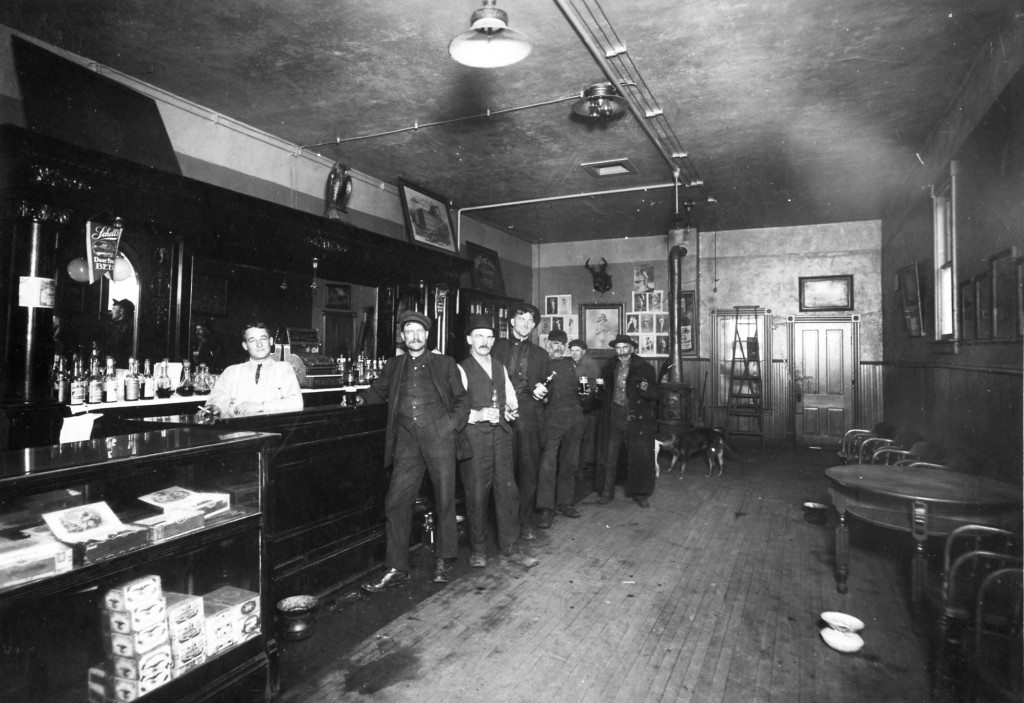

In 1909 applications for liquor licenses were submitted by William Krebs, John Hinkle, John Sandberg, George Williams Jr., and George A. Werner. Sandberg and Williams were at least initially denied. The cost of a license was $7 for one year. In June, the closing hour of saloons was moved from 11 pm to 10 pm except for Saturday, where it stayed at 11. In October, A.E. Blacktin was approved to run a pool room in the Walker Block. And here we have John Hinkle, proprietor of the Hinkle Hotel, 36th and Brunswick, requesting permission to make an office of the saloon on Sundays. Werner’s saloon was no doubt inside one of the hotels on Brownlow. The photos below are inside that establishment.

1910 – Wet

The Minneapolis Tribune reported that St. Louis Park voted wet in the annual March election, albeit with a close vote of 151 to 143. But Village council minutes indicated that applications for liquor licenses submitted by George Werner, John Hinkle, and William Krebs were denied after pleas from Rev. R.S. Cross, G.M. Whipple, M.R. Martin, E.S. Hatch, F.L. Carter, T.H. Colwell, and H.L. Hamilton. There were also letters of protest from the Minnesota Assistant Attorney General and the Secretary of the Minnesota Anti-Saloon League, as well as letters from three attorneys. Krebs and Werner went on to get pool table permits.

This article from the October 13, 1910, Minneapolis Tribune seems to indicate that liquor was still around, though:

Rear Chamber of Sheriff’s Office Filled With Seized Drinkables

Visitors to the sheriff’s office are at a loss to tell whether the rear room is a place for officials or a repository for beverages confiscated by the deputies. Since the raid on the St. Louis Park houses Sunday, this room has been made a vault in which to stow a large number of barrels and boxes of seized “wet” goods.

There are 20 and a quarter barrels of drinkables, five of them labeled “table malt.” There are several cases of bottled goods all said to contain intoxicants. These are artistically arranged about the barrels.

A huge temperance parade took place on May 14, 1910. Expected to participated were:

- 200 organizations in 14 divisions

- 50,000 participants

- 30 bands

- cars for all women participants

In December 1910 John Hinkle, proprietor of the St. Louis Park Hotel, was accused of operating a “blind pig” or unlicensed liquor emporium but was found not guilty: (Minneapolis Tribune December 9, 1910)

The evidence submitted by the defense hinged on the question of whether the liquor bought at Hinkle’s was beer or malt. The deputy sheriff who gathered the alleged beer used an atomizer to get the liquor served to him by Hinkle. An analysis made by the city showed that the liquor ran within .002 of the amount of alcohol of that in the beer sold by a local brewery.

There proved to be some sediment in the atomizer that the beer, or malt as it was claimed to be by the defense, was brought to the city in, and John Berhagen, attorney for Hinkle, declared that the presence of the sediment would make it impossible to make a true analysis of the liquor. The jury agreed with Mr. Berhagen and found not guilty.

1911 – Wet

In January 1911 L.L. Doc Brown was approved for a pool room. This is a scene from Doc Brown’s pool room.

The March 1911 election had “lots of real red fire works.” The drys had hopes of winning by making arrangements for street cars to bring men from Minneapolis (who had business and winter homes there) into St. Louis Park for 15 minutes “to allow the passengers time to cast their ballots and catch the same car back to the city.” (Minneapolis Tribune March 14, 1911). It didn’t work: the village went wet by a vote of 192 to 116. George Werner, John Sandberg, and John Hinkle were approved for $700 liquor licenses. That October, John Sandberg’s license was transferred to Alfred Johnson. One interesting note in December – the Recorder was ordered to take the money from the liquor licenses and make it available for the maintenance of the State Inebriate Asylum.

A big event in 1911 was when T.B. Walker’s Methodist Church and George Werner’s saloon across the street caught fire and the volunteer firemen arrived and found them engulfed in flames. They knew they couldn’t save the church, so they went across the street to try and save the saloon. The minister saw the firemen go over to save the saloon and he cried out “They’re letting God’s house burn and saving that Devil Establishment over there!” Or so the story goes. The church did survive but was destroyed by a tornado in 1925 and not rebuilt.

1912 – Wet

In the 1912 election the wets argued that if the village went dry everyone would go to Minneapolis to drink and it would cause havoc on the street cars. Street railway officials were sure that they could control the situation. George Werner, Alfred Johnson, and John Hinkel were approved for liquor licenses. Doc Brown also added a pool table. Tony Dangelo’s request for a license to put two pool tables in M. Dworksy’s building at 608 Highland was approved. Highland is now 36th.

1913 – Wet

In 1913 again Werner, Johnson, and Hinkel were awarded licenses for $700 each. Starting in 1913 until 1916, both Doc Brown and Elmer Whipps were on the permit to run three pool tables and sell cigarettes.

1914 – Wet

In 1914, in an election with the largest vote ever cast, the village stayed wet in a 215 to 153 vote. Werner, Johnson, Hinkel, and a newcomer, Andrew Peterson, each paid $800 for a liquor license. But on the down side, the Village Marshall was ordered to remove all slot machines.

1915 – Wet

It’s 1915, and Andrew Linder has a permit to sell cigarettes. Werner, Johnson, and Hinkle have their cigarette permits.

“A vain attempt to eliminate the saloons from St. Louis Park resulted in a victory for the ‘wets’ by a vote of 203 to 148.

In September 1915 there was a barrage of meetings at schools and churches, including St. Louis Park Congregational Church.

1916 – Dry

In 1916 the wets lost, but only by 6 votes, 197 dry to 191 wet. The PTA appeared before the Village Council to urge the closing of pool halls on Sunday. No action was recorded.

A committee of 85 churchmen appealed to the public to behave themselves on New Year’s Eve and to refrain from orgies of revelry and gross excesses in eating and drinking. “Notoriously this has been the deplorable habit in downtown Minneapolis for many years and the like demoralities of our youth has not been unknown in other parts of the city.”

1917 – Dry

1917 sees the entry of Dutch Reider into the fray. In February he requested a permit to sell cigarettes. Then it was Reider and Whipps who were granted a permit to operate three pool tables next to the Waiting Station. Doc Brown is apparently now on his own, with a permit to operate three pocket billiard tables.

On March 13, 1917, the drys won by one vote, 212 to 213. [The Minneapolis Tribune reported that the vote was tied at 212, which meant that the village would remain dry.]

Also in 1917 the Minnesota Public Safety Commission asked the Village Council to enact an ordinance covering their Order #14 pertaining to the regulation of pool halls and public dance halls. This ordinance came about in January 1918.

1918 – Dry

An ordinance passed on January 16, 1918, set poolroom hours at 8 am to 11 pm, closed on Sunday.

In February Superintendent of Schools Hatch gave a talk on the effects of the use of liquor at the monthly meeting of the Hennepin County Teachers’ Association. E.M. Beal, Principal at Maple Plain, gave a similar talk on the evils of tobacco.

In March 1918 the drys won by three votes.

But pool tables were still hot – Reider and Whipps paid $10 to run two pocket billiard tables in April 1918.

State beer drinking (and revenue) fell 35 percent between April 1917 and April 1918, according to a May 5, 1918 article in the Minneapolis Tribune. Beer consumption in Minnesota fell from 112,918 barrels to 72,644. This may have been due to a temporary World War I limit of 2.75 percent alcohol percentage in beer.

Also in 1918 the Village purchased a former saloon from a Mr. Carlson of the Minneapolis Brewing Company for $2,000. The building, which was operated as a saloon by George Haun at 36th between Brunswick and Dakota, became the new fire barn.

The history of the Mothers’ Club of Lincoln School for 1918 includes: “Attention was called to the Dry Amendment and members were asked to use their influence to make Minnesota dry.”

The 42nd Annual convention of the Minnesota WCTU met in Duluth on September 17 – 20, 1918. Topics under discussion, as reported by the Minneapolis Morning Tribune, would be women in war industry, war activities of the WCTU, moral education as applied to army camps, Americanization, and Miss Kate Kercher of Brookside speaking on food conservation and war gardens. The WCTU would continue their works after prohibition was enacted. A 1922 article found them giving a benefit musical show to raise funds for a “mother-child” center for foreign speaking women in the city. The group provided a sermon and flowers to 921 prisoners at Stillwater. Kate Kercher hosted the annual picnic of the 17th District; attendees were to take the Como-Hopkins streetcar to get to her Brookside home.

And just in case any happy Parkite had thoughts of celebrating Armistice Day in Minneapolis, the Minneapolis Daily News of November 11, 1918, reported that, upon the advice of the City Health Commissioner, the Minneapolis Chief of Police ordered all Minneapolis saloons and cafes closed for the day. They will remain closed until after the voluntary peace celebration undertaken by the people upon receipt of news the armistice between the allies and Germany has been signed. This was primarily because the city was still subject to the Spanish Flu epidemic, and all places where crowds might gather, such as soda fountains, would also be closed.

1919

Dutch Reider and Elmer Whipps got a permit to sell cigarettes at the Waiting Station in March 1919, but their request to operate the pool hall on Sunday was refused.

1920

Again in 1920, Whipps and Reider operated pool tables in the south room of the Waiting Station.

Summing up the pre-Prohibition saloons:

Conrad Birkhofer: 1902-1904

John Hinkle: 1909-1915

Alfred Johnson: 1911-1915 (permit transferred from Sanberg)

William Krebs: 1910

Morton: 1905 (permit transferred from Ohde)

August Ohde: 1904 (permit transferred to Morton 1905)

Charles Perry: 1907

Andrew Peterson: 1914

John Sandberg: 1906-1911 (transferred to Johnson)

Fred Wallin/Whalen: 1903-1906

George A. Werner: 1909-1915

J.S. Williams: 1904

PROHIBITION

Keep in mind that St. Louis Park went dry in 1917, three years before the nation.

The 18th Amendment to the Constitution, was passed by Congress on December 18, 1917. It was ratified by three fourths of the State Legislatures on January 16, 1919. Section 1 reads:

“After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.”

THE VOLSTEAD ACT

Congress passed the 12,000 word Volstead Act (actually the National Prohibition Act), which was the enforcement legislation, in October 1919 over the veto of President Wilson. The Volstead Act spelled out the specific prohibitions, definitions, exceptions, and penalties.

Andrew John Volstead, a 10-term Republican Congressman from Granite Falls, Minnesota, and chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, more a facilitator of the law than the author – the architect was really Wayne Wheeler of the Anti-Saloon League. Nevertheless, Volstead was a firm believer; the conclusion of an undated speech demonstrates his fervor:

I am proud that America is leading in this great movement. The eyes of the world are upon us, and from innumerable homes, here and beyond the seas, prayers go up for the success of the cause. Are we going to disappoint them? No! A thousand times no! the men and women who wrote the prohibition amendment into the National Constitution will, I am sure, sustain it. A nation that was brave enough and generous enough to give millions of its men and billions of its money in the World War will turn aside with contempt from the sneers and taunts of those who selfishly and petulantly insist that their right to indulge in intoxicating drinks is superior to all law and more important than the public good.

The nation went dry overnight on January 16, 1920. Selling alcohol – beverages containing more than one-half of one percent alcohol – became a Federal crime, although the 18th Amendment stipulated that “The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” States passed their own prohibition laws, as apparently did cities and villages: we find that the 1926 reconciliation of St. Louis Park ordinances (A-14) defined intoxicating liquor as “ethyl alcohol and any distilled, fermented, spiritous, vinous or malt liquor.”

There were several exceptions outlined in the Volstead Act, including sacramental wine (leading to many a phony priest and rabbi), homemade cider, industrial alcohol, alcohol prescribed by a doctor (no more than a pint every ten days), flavoring extracts, syrups, and vinegar. You could make “near beer” with less than .5 percent alcohol but you couldn’t call it beer.

You could also drink all the alcohol you wanted, as long as you had purchased it before January 17, 1920. Many people stockpiled the stuff, and bottles are still being found squirreled away in attics today.

As for Volstead, he lost his re-election campaign in 1922 and died in 1947. A portrait of him made of beer bottle caps can be seen in the Volstead Lounge at the Freehouse Brew Pub, 701 N. Washington Ave. in Minneapolis.

WHY PROHIBITION?

Prohibition came about for several reasons, and several books have been written about it. One impetus was the proliferation of saloons where men could go to get away from their families and potentially spend the rent money. Women won the right to vote in 1920 and were becoming more and more influential in public opinion, and they wanted their men out of the saloons.

Second, there was the German factor. The U.S. entered into World War I on April 6, 1917, and the country railed against anything German, which included beer. What didn’t help is that the brewers were overwhelmingly German and didn’t repudiate the actions of Germany sufficiently.

Another reason was racism; southerners wanted to keep alcohol away from blacks for fear they would get drunk and commit crimes against whites. The Ku Klux Klan participated in this line of thought, although arguably they hated Catholics just as much as whites, and Catholics were notably “wet.”

Yet another factor was financial. The Sixteenth Amendment was passed in 1913, allowing the Federal Government to collect income tax for the first time. This meant that money lost from taxing liquor could be made up for with income taxes. Needless to say, the big capitalists of the time did not appreciate this incursion into their fabulous incomes, and their opposition to prohibition was a major factor in getting it repealed. Unfortunately, the return of liquor taxes did not make income taxes go away as they had hoped.

And not to be forgotten was the skill and tenacity of Wayne Wheeler of the Anti-Saloon League, who was able to influence elections in tight races.

BOOTLEGGING

Bootleggers flourished during Prohibition, and locally the biggest was Isadore “Kid Cann” Blumenfeld (1900-1981), who led the “Minneapolis Combination.” This benevolent group apparently not only supplied hooch locally, but ran it down to Iowa as well.

In Minneapolis the speakeasies were concentrated in the Gateway District, which was known for its wall-to-wall bars, liquor stores, and flop houses. They lasted until well into the 1950s, when Urban Renewal came along and leveled the area, displacing up to 3,000 “skid row bums,” many of them WWII Veterans.

Outside of town in St. Louis Park, bootleggers were everywhere, selling “Old Popskull” at chicken shacks along Excelsior Blvd. Cottages along the creek were rented for weekend partying. 5 cents bought a regular Coke, 25 cents bought you a Coke with a little something extra.

Unregulated by the Government, the quality of the liquor was unpredictable and often dangerous. Ben Brown remembers that “there was much public drunkenness, and drinkers spiked their drinks far too heavily and became drunk in short order. It was very common to see men staggering down the street and sometimes fall and lay on the road or sidewalk. A pitiful sight to witness.”

Ben’s dad Doc Brown himself made home brew, and could always count on a ride home from his Barber Shop and Pool Hall from someone who would be invited to partake. One of his main drivers was said to be the Village Constable – perhaps his friend Elmer Whipps?

Ben also remembers when “one bootlegger just down the block from Doc Brown’s Barber Shop and Pool Hall was raided several times by the Feds, but they never found anything. Turns out there was a rubber hose in the drain plug in the bathtub that led to a secret storage area underneath.” A local plumber may have been involved with such riggings…

It just may be that the local plumber was Tom Motzko. His son Frank tells the story about how his father did the plumbing for the Glen Lake Sanitarium, but made more money selling moonshine than the plumbing. Everything the family had was first class!

Mike Jennings, later of Jennings Tavern and Liquor Store, was said to be active in his line of work before 1933. One day it was reported that the Feds raided a house that Mike had rented from Jimmy Murphy for $75 a month, in a day when rents were typically $16. (This was the same Jimmy Murphy who had one of the first gas stations at Excelsior and Brookside, and who turned down the chance to buy all the swampland in Skunk Hollow for $100.) The raid yielded dozens of 5-gallon cans, which the Feds punctured with axes and poured out on the ground in the vacant lot next to the house.

Another story about Mike is that he was in cahoots with a depot agent in North Dakota. Liquor was shipped from Canada to a fictitious name in this North Dakota town. The depot agent would then auction off the “unclaimed” freight and Mike was always the buyer. Then drivers would deliver it to the Twin Cities. It turned out that Minnesota, home of Congressman Volstead, was particularly conducive to bootlegging, having a long border with Canada, and the nearby North Dakota border was easily crossed on old farm roads. My Canadian Uncle Alf says that Studebaker made a special car to accommodate the rumrunners. It was made with an extra heavy frame, had heavy-duty wheels and tires, was extra long, and had the most powerful engine made in the U.S. It was marketed as a seven passenger family car, with two folding seats installed in the very large floor space between the front and back seats. This car could transport a ton of hooch at high speed.

Mike Jennings was succeeded by his son Jim. Another son, who worked for Honeywell during the war, perished when his plane disappeared.

Another name associated with evil drink was W. Scott “Scotty” Hudson, a Village Character with No Visible Means Of Support (although phone books in the ’30s listed him as a “lather” – like in the wall?). At one time Scotty lived in a shack underneath the Village water tower.

1922

Some St. Louis Park kids almost got lucky in September 1922. Seems the Prohibition agents were chasing a bootlegger named Frank Barbeau when a dozen gallon tins of booze fell over the side of the fleeing car. The intrepid agents got their man and managed to track down the boys (who now numbered 11) and find the cache of liquor. Too bad.

1925

To try to attack the problem, Congress passed the Jones Act in 1925, which greatly increased the amounts of fines and jail time for violators of the Volstead Act. But that was Federal law, at a time when states were repealing their own prohibition laws as unenforceable.

1927

Here’s a puzzler: The Yellow Trail Garage in Hopkins advertised a gallon of 188 proof alcohol for 80 cents in 1927. In BIG ads in the Hennepin County Enterprise.

Bootleggers in Edina; Sheriff Seizes Plant (Hennepin County Enterprise, September 1, 1927)

Sheriff Earle Brown and his deputies seized a plant of contraband whiskey in the peaceful village of Edna. The plant and contents is valued at $10,000. One man is being held by the sheriff for examination.

The place where it was found was a spacious residence, of old time architecture, and according to Sheriff Brown, the plant was the most completely equipped establishment for its purpose, ever unearthed in Hennepin County.

It is supposed that the bootleggers had been there only a short time and that the location was selected for its obscure surroundings and was intended as a base of supplies for the dealers of Minneapolis.

The bootleggers made the mistake of not keeping their warehouse in Minneapolis. It is extremely dangerous for them in Sheriff Brown’s domain.

The nefarious Edina bootlegger was subsequently identified as Roy Stanchfield, who was arraigned before Judge Ray W. Meeker of Richfield on a charge of maintaining a nuisance, and was sentenced to 60 days in the workhouse. “It is supposed that the prisoner had connections with a notorious gambler and underworld character who lives in the neighborhood and that the immense quantity of contraband liquor was intended for the state fair trade.”

1928

In April 1928 Minneapolis played host to Dr. James M. Doran, Federal Prohibition Commissioner, who came to confer with S.B. Qvale, district administrator, and for an inspection of the northwest bureau. He had good things to say about Minnesota, saying it was “regarded as one of the nation’s driest states” and that “only a minute quantity of liquor is filtering through.” Most of the problem in the north was in the Detroit area.

However, the sore spot in our area was in the sale of soft drinks and ice (setups) “to persons known to be drinking.” “Dr. Doran predicted that eventually the United States will be completely dry, but admitted that this will take a long time.” He also predicted, “Prohibition is here to stay and is making itself felt as a material factor in the present social and economic condition of the country, which is better than anywhere else.” (Minneapolis Morning Tribune, April 21, 1928)

1929

An unconfirmed rumor was that Dutch Reider had hot and cold running hooch in his bathroom, or so the neighborhood kids (and the police) liked to speculate, and he was raided several times. On July 19, 1929, he was accused of selling intoxicating liquor to one Ray Paulson. Officer Earl Sewall and four other officers executed the search warrant, arrested Dutch, and confiscated “a quantity of intoxicating liquor and one five Gallon jug.” Dutch pleaded guilty to maintaining a nuisance, and was fined $100. Making moonshine was a Federal offense, and Dutch could have spent some time in the Federal penitentiary.

Police confiscated three gallons of moonshine from Charles Stine in September 1929. Mr. Stine was a “cripple,” and as he couldn’t move, he couldn’t appear in court. He also had no money. He was referred to the Health Commission.

1930

In February 1930 Henry Melius was caught with 1-1/2 gallons of wine, a whisky glass, and four one-pint bottles. The address was 6325 Minnetonka Blvd., which at the time was probably a grocery store (since 1957 the home of Beek’s Pizza). He plead not guilty but was fined $50.

1932

1932 joke: “Why did you name your baby Capone?” “Because he has no regard for the dry law.”

Then there’s the story about a Saturday night “party” at one of the speakeasies and how the one-man Park Police force took the drunks home with him rather than take the time to haul them all the way to the Minneapolis hoosegow, as it was too far. St. Louis Park’s two-cell jail was more of the “Mayberry” variety and couldn’t possibly handle the volume.

Even the Town Band got carried away, it seems. An oft-told story concerns a 4th of July engagement in Chanhassen. Ben Brown remembers, “The band caught the train in St. Louis Park and rode straight to Chanhassen. One member couldn’t make the train that morning, so he walked the railroad tracks all the way. He couldn’t locate the band, so he inquired as to where they might be. The people of Chanhassen wanted to know why he wanted to find the band, and once they found out he was a member, they ran him out of town without so much as an explanation. He soon learned that the band had arrived early, got drunk, and raised particular hell so they were all run out of town. And then this poor guy arrives late after walking from St. Louis Park and asks, ‘Where’s the St. Louis Park Band?'”

In 2013 the Minnesota History Center presented an exhibit on Prohibition, moonshine, and bootlegging. See articles Here and Here.

REPEAL

Congress passed the Blaine Act which would repeal Prohibition in February 1933, but the 21st Amendment had to be ratified by the states, which took until December 5, 1933. Prohibition had lasted 13 years, five months, and nine days. Meanwhile, on April 4, 1933, Congress passed the Cullen-Harrison Act (or the “beer bill”) that declared that 3.2 percent beer was “non intoxicating.” Previously, beer with more than .5 percent had been considered intoxicating. The 21st Amendment gave the regulation of alcohol back to the States. Apparently things were a little fast and loose at first, judging by the ads placed by local drug stores and even gas stations offering beer on tap. Now there’s a good idea.

In early 1934 Minnesota passed a bill giving localities the option of allowing the sale of liquor, but also instituting certain statewide restrictions such as dry Sundays.

Park’s new liquor ordinance “relating to the sale of non-intoxicating malt liquor or beverage” was passed on March 31, 1934. The Village Council approved nine licenses for “non-intoxicating liquor” (aka beer) right away

“Hard liquor” licenses had to wait until a Village general election was held in December 1934. On November 29, 1934, the “St. Louis Park Taxpayers Assoc.” placed a large ad in the Hennepin County Review urging

Vote For License!

On all sides of St. Louis Park liquor is being sold under license [legally]. It is therefore desirable that St. Louis Park should also vote for license in order that we be the better enabled to cope with the sale of liquor in the Village, protect our citizens, and at the same time derive some benefit from the sale thereof.

Reasons for voting to allow liquor licenses to be issued were primarily to collect revenue, control drinking in the village, discourage people from buying elsewhere, and doing away with the bootleggers. The electorate overwhelmingly agreed, with a vote of 1,165 to 473 on December 12, 1934.

The first license approved was to Harriet W. Jennings, wife of former bootlegger Mike. Liquor licenses were approved for James A. Roach, Al Lovass, Walter G. Poirer, Bunny’s, El Patio, and the Belmont Tavern, among others. Henry Allen ran a beer joint called “O’Neil One Acre,” location unknown but probably in connection with the riding stable.

Although St. Louis Park became known for its drinking establishments, especially along Excelsior Blvd., there were three council members – Torval Jorvig, Herman Bolmgren, and Recorder Joe Justad – who were teetotalers and did their darndest to keep down the number of liquor licenses. Bob Jorvig says that his father used to visit the bars armed with a handmade wooden bat and make sure they closed on time.

The new liquor ordinance prohibited minors to be in beerhalls, but parents protested that their children could no longer work there, so each parent had to individually request permission for his child to work. On May 2, 1934, Mr. P.K. Anderson received permission from the Village Council for his daughter Evelyn to work at the restaurant.

One thing to note is that drinking levels did not rise to those of the previous saloon days until the 1970s.

A look at Justice Court records from 1935-36 reveals the following:

- On March 11, 1935, Mr. RM Johnson was fined $25 for “keeping and harboring a slot machine.”

- On May 29, 1935, Clifford Kitchen was fined $25 for keeping and maintaining a gambling device with money, a slot machine.” He was also fined $92 for keeping the place open after 2 am. Again that September, Kitchen’s place was raided and he was fined $10 for having a gambling device. The address was that of Ann and Andy’s Tavern on Wayzata Blvd.; at least it was in 1941.

- On June 7, 1935, James Murphy, 8800 Minnetonka Blvd. (not an address today) was fined $85 for keeping his establishment open after 2 am.

- On June 29, 1935, Nick Sateropolis of the El Patio Restaurant was caught selling liquor to minors as young as 9. For that he was fined $25. He was also cited for keeping, storing, and selling fireworks without a license. He was fined $25 plus $4.45 in court costs. He appealed, and if we’re reading this right, got a $100 fine plus $6.90 in fees or 60 days in jail.

- On August 8, 1935, JW Roach was cited for selling intoxicating liquor illegally at his tavern at 4315 Excelsior Blvd. Sidney Moe was also cited. They asked for a change of venue.

- On August 12, 1935, Emily Knoss from Hopkins was fined $25 for selling intoxicating liquor at 8550 Minnetonka Blvd. The fine was suspended.

- In 1936, George Braumas, Secretary of the El Patio organization (3916 Excelsior Blvd.) was found with 2 bottles of gin. He was declared not guilty when he stated that they were his personal property.

THE EXCELSIOR BLVD STRIP

By 1934, Excelsior Blvd. had about six or seven (or 14?) beer joints that were open 24 hours, and the noise made it impossible for nearby residents to sleep. One such resident was Morton Arneson (1893-1982), who had bought three acres on Excelsior Blvd. and Quentin Avenue and established his nursery business, the first of five such nurseries on the Boulevard, at 4951 Excelsior Blvd. in May 1929.

In his memoir, Arneson told of one particularly hot night when the racket was worse than ever; the band in the speakeasy across the street (probably Walt’s Canteen, across Quentin) played three pieces on the banjo, one after another, and when they were through they started all over again. Finally, the family departed to a friend’s house way out of town to get some sleep. He suspected the Kid Cann gang and the police (and possibly Mayor James H. Brown) of being in cahoots. Regardless, although the law that required establishments to close at midnight, it was not enforced, and those who complained were told to go back to Minneapolis if they didn’t like it.

Ah, but an article dated February 6, 1942, tells us: “Council Serves Notice it will Tolerate No More Liquor Violations in Village.” The action came in the wake of a hearing where Henry Aretz was accused of selling alcohol at Bunny’s, although it was unclear whether the issue had to do with selling to a minor or selling on a Sunday. Many citizens gave their opinions both for and against yanking Bunny’s license.

The liquor business was put under attack in October 1945 when the Committee for Tax Savings, led by Hugh McElroy, called for a municipal liquor store. The attack was rebuffed.

Then there was an undated flier issued by the Liquor Dealers’ Assn., Al Lovaas, Chairman (Al of Al’s Bar). The flier was addressed to the Voters of the Village of St. Louis Park and made an impassioned plea to retain the status quo, citing revenue from the sales of liquor, dances license fees, pinball license fees and more. 67 people were employed full time, and 107 would be put out of work and on Relief if the bars were shut down. Tax revenue would be lost, and those who “want wines and liquors [will] step across the line to Minneapolis, Golden Valley, Edina, and Hopkins, where the same can be obtained.” The return of the Bootlegger was even listed as a possible threat if the legal, orderly, licensed and controlled conditions were eliminated. The barmen ultimately prevailed.

Former councilman Keith Meland explained that one reason for the success of the bars and restaurants along Excelsior Blvd. was a Minneapolis ordinance that did not permit liquor to be sold south of Franklin Avenue – the so-called “patrol limits ordinance.” Indeed only one liquor vendor existed in South Minneapolis, and that was the President Cafe, located across from the old Nicollet Ball Park. Edina allowed no liquor, and the only place you could get it in Bloomington was the old Oxboro area south of 86th Street. The best place to buy your liquor if you were a resident of South Minneapolis was St. Louis Park. In addition, almost all of the Park establishments had combination licenses that allowed them to sale packaged liquor and sale by the drink. The Foo Chu, Jennings, Bunny’s, Al’s and the El Patio, among others, had combination liquor licenses.

LIQUOR IN THE POSTWAR ERA

1947

In 1947 Carl Reiss had to get Council permission to employ his son Richard, 20, in his bar and liquor store.

In 1947 pinball machines were supplied by the Automatic Piano Company and the Apex Amusement Company. In 1948, the Mercury Sales Co. and Coin-A-Matic Amusement Co. received licenses for pinball machines. They were operated at Al’s Bar, El Patio, Bunny’s, Reiss’s, Ray and Arnie’s, Lilac Lanes, and the Park Tavern.

1949

In 1949 bars were closed on Sunday (except from 12-1am). They closed at 3pm on Memorial Day and 8 pm on election day. Off sale liquor could be sold from 8am to 8pm, except Saturday nights when they were open until 10 pm.

1952

The Village Council was just not awarding liquor licenses; in January 1952 they turned down 10 applications, five of which were for a liquor store at Miracle Mile. Those applicants were Ernest A. Clifford, Fred Gates, Gerald T. Kelly, Elwood L. Mason, and Robert M. Pratt.

The Minneapolis Spokesman reported that the Twin Cities had been smeared in an article in the September 1952 issue of Stag Magazine called “Twin Cities of Sin,” written by Frank Rasky. Whatever the sin was, the Cities had it: strippers, drunks, gamblers, dope peddling, gangsterism, pornography, prostitution, and this: “there was one dope addict for every 25,000 of the population in Minnesota.” He cities the corruption involved with the streetcar takeover by Fred Ossanna and friends, and names all the streets where one could find all these evil deeds. The Spokesman pooh-poohed the article – after all, it’s Stag Magazine!

1955

When St. Louis Park became a charter city in 1955, under State law it was allowed to issue up to 15 on-sale liquor licenses. The previous maximum had been ten, although thanks to the efforts of stalwart teetotaling councilmen Torval Jorvig, Joseph Justad, and H.J. Bolmgren, only six had been issued:

- Bunny’s

- Culbertson’s

- Park House

- Lilac Lanes

- Al’s

- McCarthy’s

The Minneapolis Golf Course also held a club license.

As of January 1955 there were nine off-sale licenses:

- Bunny’s

- Culbertson’s

- Giller Drug

- Andy Johnson’s

- Jenning’s

- Texa-Tonka Liquor Store (Harold Kaplan, first issued in 1953)

- Al’s

- McCarthy’s

- Reiss’s

In September 1955 a brou-ha-ha ensued when Andy Johnson sought to sell his off-sale liquor license to three men who would use it to establish a liquor store at Knollwood Plaza. Although there was no legal restriction on the number of off-sale licenses that could be issued, Knollwood had been turned down again and again. Councilman Caroll Hurd said that the plan to actually “sell” a license and thereby go around the city council “stinks to high heaven.” It’s possible that Knollwood did not get a liquor store until 1962.

1957

On June 24, 1957, the Council passed a new ordinance regulating the spiking of drinks with alcoholic beverages in public places.

1958

Just before Christmas, 1958, the City Council passed an ordinance licensing and regulating “bottle clubs.”

1959

On May 25, 1959, the City Council passed Ordinance 694 prohibiting the keeping or consumption of intoxicating and non-intoxicating malt liquor beverages in motor vehicles on public highways.

By 1959 the City had only issued six on-sale liquor licenses, although it was authorized to issue 15. Mayor Ken Wolfe called for public meetings to investigate all applications, and as a result, a license was issued to Knollwood Liquors, the first of its kind in the rapidly-expanding part of town.

1960

In 1960 an article appeared in a Minneapolis paper that said St. Louis Park’s “strict beer ordinance, passed just after prohibition ended” was up for discussion. The problem came up because bowling leagues were refusing to play at Texa-Tonka Lanes because no beer was served.

1968

In 1968 the City experimented with special permits to sell drinks on Sunday. The first applicants were McCarthy’s, Lincoln Del West on Wayzata Blvd., the Royal Court at Knollwood, and George’s in the Park. They were approved in April 1968.

Former City Councilman Keith Meland explains that the land that was originally slated to be Candlestick Park was encumbered by a restrictive covenant that only allowed alcoholic beverages to be sold in connection with major baseball. Even though Candlestick Park never materialized, the covenant continued to prevent any establishment on the property from serving alcohol. With the help of Eldon Rempfer, a Park resident and shareholder of in the MBAA (owners of the land), the covenant was removed and the Lincoln Del and the Ambassador Hotel were able to get liquor licenses for the first time.

1969

In January 1969 the Echo had an editorial entitled “Better conduct demanded now” that indicated that it took policemen on duty at dances to frighten away the “usual trouble-making-Friday-night-drinkers.”

1970

In 1970 George Faust’s restaurant was accused of serving liquor to a 20-year-old without ID, which led to a car accident. A special council meeting was held, and the restaurant’s on-sale license was suspended for 10 days.

1973

In 1973 George Faust’s was caught selling alcohol to a minor – a 20 year-old girl with two fake IDs. He was given a 10-day suspension of his liquor license, but it was temporarily rescinded when he told the council that it would cost him $10,000 in business and force him to close down.

On June 1, 1973, the age of majority – and thus the drinking age – was changed from 21 to 18 in the State of Minnesota. The drinking age in Iowa, Wisconsin, South Dakota, and bordering Canadian provinces all had a drinking age of 18 at the time. 205,000 people in the state were affected, 20,000 in the Twin Cities. Regulars at the bars were leery at first of the new teenagers, but kids flocked to the watering holes of Excelsior Blvd. and to discos like Uncle Sam’s in downtown Minneapolis. The change in the age of majority also affected contract obligations and responsibility for criminal acts.

1977

The drinking age in Minnesota was raised from 18 to 19 in 1977.

1983

In 1983, at the urging of Pillsbury, Park Council members re-wrote the City’s on-sale liquor license ordinance to allow one owner to have two liquor licenses as long as he built the second establishment. The owner of the Lincoln Del cried foul, as he had been trying to get liquor licenses for both of his existing restaurants for years.

1986

On September 1, 1986, the drinking age was raised from 19 to 21, with a grandfather clause that allowed people who were at least 19 on that date to drink legally.

2011

Steel Toe Brewing opened its doors as a family-owned craft brewery in August 2011 at 4848 West 35th Street. Initially it was open only a few hours a week for customers to purchase a growler. After local laws were changed to allow taprooms, in 2013 the company built a bar to serve its beer and would coordinate with a Food Truck to park in the parking lot offering food. The tap room was very popular and would fill up quickly, so in 2015 it expanded its taproom.

2015

On January 20, 2015, the City of St. Louis Park placed a moratorium on any future liquor stores, to last until December 31 of that year. The number of liquor stores per capita in the Park had become alarming and many were very close together.

SOURCES:

Two good books on Prohibition are Prohibition: Thirteen Years That Changed America by Edward Behr (1996) and Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition by Daniel Okrent (2010).

“Andrew Volstead: Prohibition’s Public Face,” by Rae Katherine Eighmey, Minnesota History, Winter 2013-2014, pp. 313-323