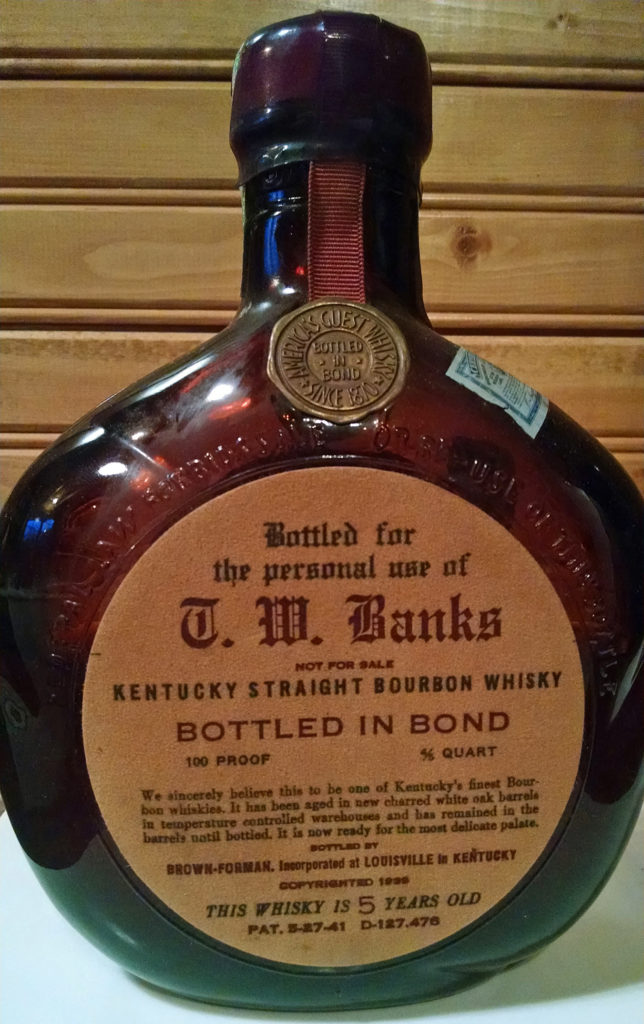

The 1952 book USA Confidential said, “[Gangster Kid] Cann is notorious. But the undercover power is Tommy Banks, owner of five liquor stores, the man who can put over anything.” Indeed, much more is known and has been written about Isadore Blumenfeld, alias Kid Cann. But Tommy Banks quietly made millions running bars and liquor stores in the 1940s and ‘50s, regardless of the fact that he was a convicted felon and could not legally own a liquor license.

His link to St. Louis Park was primarily as the proprietor of McCarthy’s Cafe, which was located at 5600 Wayzata Blvd. from 1942 to 1968.

This page is based on the hundreds of pages of documents provided to the Society by Loren Hill, and we thank him for his work and for sharing it with us! Also many thanks to Mike Brey, who has provided information and photos. And many additional articles came from the clipping files in Special Collections, Hennepin County Library, Downtown Minneapolis.

NEBRASKA

Thomas William Banks was born on August 4, 1894, in Hershey, Nebraska.

His father, Clinton Charles Banks, was a dry goods merchant – one article described him as the the owner of the first general store in Lexington, Nebraska. He died in 1928 in Los Angeles, presumably living with or near daughter Grace.

Tommy’s mother’s maiden name was Lula May Ritter.

Tommy’s siblings were:

- Grace Kay, born @ 1890. She married Clyde Schick, who died on or before 1952. In 1937 Grace opened the Schick Store in Long Beach, California, where she sold exclusive ladies clothing. The store was very successful, and expanded in 1949. She was highlighted as a successful American business woman in the local paper in 1957, although curiously the article never gave the name of her store.

- Churchill Howe, born @ 1893. In 1952 he operated a store in Lexington, Nebraska.

- Ruth, born @ 1896. Married Lawrence Strohl, had one child. In 1952 she was a widow and worked for sister Grace in Long Beach.

- Harold Hershey, born @ 1898. In 1952 he operated (presumably a different) store in Lexington, Nebraska.

- Guy Taylor, born @ 1901. Formerly a salesman, in 1952 Guy was a “hopeless alcoholic and now in the State Hospital at Nebraska.” In 1954 he was identified as living in Denver.

A 1954 prison report says that two of his siblings wrote that he was a healthy and happy child and got along well in school. In 1900 the family lived in Cozad, Nebraska.

Lula died on August 1, 1905, when Tommy was just 11 years old. One government document says that she died during an operation.

At one of his trials he testified that he ran away from home at age 13, which would have been 1907. The 1954 prison report found it odd that he would run away from such a fine home; “Perhaps he was disturbed by his mother’s death.” Tommy liked to say that he was on his own ever since, but that does not seem to be the case.

In the 1910 Census the family, including 15-year-old Tommy, is located in Lexington, Nebraska.

When he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, at age 23, he listed Cozad as his home address, occupation “farmer.”

A character witness for Tommy in 1952 claimed that Tommy was employed at his hotel in Omaha in 1917.

BOISTEROUS DRUNK

Another interesting tidbit from this friend, whose name was redacted from the 1952 document, was information on Tommy’s drinking.

During the years [Tommy] was drinking he sometimes made a nuisance of himself. When he was under the influence of liquor he became quarrelsome and wanted to fight and did become involved in pugilistic encounters. However, [the friend] knows that Tommy at no time ever carried a gun. Several years ago he quit both drinking and smoking and since then he has been a perfect gentleman.

Another witness said that when Tommy used to drink he used to become VERY bellicose after he had a few, but that he had quit drinking and smoking. One document, that was otherwise rife with errors, stated that Tommy stopped drinking after the 1945 murder at the Casablanca (see below). Another friend said that his only bad habit was an intense craving for chocolate.

RETA

Tommy married Reta Lee on January 5, 1918, in Council Bluffs, Iowa. Reta was born on January 15, 1897, the daughter of Gabriel Lee (born in Norway) and Ellen Wells (born in Iowa).

WORLD WAR I

A friend from back in Nebraska recalled that in 1917 he and Tommy decided to join the Navy. Tommy’s draft registration card is dated June 5, 1917. The friend was accepted but Tommy was rejected. A medical report from 1954 indicates that both his feet were flat, which might explain that episode. Tommy finally did serve in the Army; his enlistment date was May 2, 1918, and release date was December 13, 1918. Perhaps the progress of the war and the ravages of the Spanish Flu on the troops made his flat feet not such an impediment. Another document, which is full of errors, says that he was released as a Corporal and became a member of the American Legion, which would have meant that he had served overseas.

In January 1920 Tommy and Reta made their home in Omaha, where his occupation was listed as Salesman, Oil Stock.

TO MINNEAPOLIS

In 1920 Tommy and Reta moved to Minneapolis. He became head bellboy at the Dyckman Hotel, running whisky for patrons at the hotel for about $100 to $200 each day. They lived in Room 1010 of the hotel, and kept this room even after he’d graduated to bigger and better pursuits. He said he quit in 1920 at age 25; he said by that time he had saved up about $12,000. He then began running alcohol from Canada to Minneapolis. He testified that he brought in $1,200 to $1,500 per week. Later he brought alcohol in from Chicago. During most of the 1920s he averaged up to $30,000 per year in the liquor traffic business, with his total earnings from bootlegging estimated as anywhere between $500,000 and $1 million.

On September 24, 1927, Tommy was indicted for bootlegging:

- 1st Count: Conspiracy to violate the National Prohibition Act, Section 37 of the Criminal Code.

- 2nd Count: Possession of unregistered still.

- 3rd Count: Possession of Mash.

On November 14, 1929, Tommy appeared before Judge Gant and pleaded guilty to the first count, for which he was fined $2,500. The other two counts were dropped.

In 1929 Banks bought a small apartment hotel at 213 So. 8th Street. The site is now either vacant land or a building built in 1955, owned by St. Olaf’s Catholic Church.) His partner was Jack Pfeiffer, and Banks testified that they were in business together for about 18 months. Pfeiffer was later convicted of kidnapping of St. Paul banker Edward G. Bremer in 1934 and hanged himself in his jail cell.

In 1929Banks was in partnership with Michael (Mitch) Code, in a distillery in the St. Paul Midway district. Code later operated the Persian Bar at 324 Marquette Ave. Banks testified that he had to go to San Francisco for two months and when he got back he found that Code had sold about $45,000 worth of liquor supplies to pay gambling losses. This loss, he said, turned him away from bootlegging and onto more legitimate pursuits. Code died in 1946.

One of Tommy’s friends (name redacted in 1952 interview) noted that the stock market crash of 1929 wiped Tommy out.

The 1930 Census has Tommy and Reta living at 4738 Lyndale Ave. and his occupation was listed as hotel keeper. Some time before 1935 they bought their house at 3817 Drew Ave. So., where he lived for the rest of his life. (The county says the house was built in 1932.)

THE SYNDICATE

During Prohibition, Tommy Banks and Kid Cann were competitors in the Minneapolis market and there was a “fierce rivalry” between them, according to a 1952 interview with Sheriff Ed Ryan. “When Prohibition was about to be repealed they combined their forces but were never close partners.” Tommy’s organization became known as the Syndicate, while Cann’s was the “Combination.” During his 1950 trial, Tommy said he could not recall any “syndicate” setup, and regarding Cann, he said, “I might have sold them alcohol, and they might have sold some to me.” At one time they even had offices next door to him in the West Hotel.

Mike Brey explains further:

Locally and according to the FBI, the Syndicate was a reference to the “Irish Mob.” It was first noted in FBI reports when Big Ed Morgan ran the rackets. Tommy became his number two guy and took over later on when Ed got too old. The Syndicate generally controlled gambling in Minneapolis

The Combination, headed by Kid Cann, was considered the “Jewish Gang.” Kid Cann and his associates had control over liquor stores.

Somehow a spirit of compromise was present with these two groups as the violent conflicts that other organizations suffered from elsewhere didn’t exist here. Tommy and Kid Cann shared many business dealings with each other over a very long period of time.

INDICTMENT

In early December 1933, 38 men were indicted for Conspiracy to violate Internal Revenue Laws, Section 37 of the Criminal Code, 18 U.S.C.A. 88. They were accused of being leaders of an alcohol ring that conspired to violate the Federal Internal Revenue Act through wholesaling, retailing, and transporting and rectifying of liquor which no government revenue tax had been paid. The government charged that the Syndicate’s headquarters was in Minneapolis and offices were operated in two downtown hotels and at 230 Second Ave. No., where a “battery of telephones was installed to handle the voluminous business.” The ring operated from January 1, 1933 to December 31, 1933. “Alcohol was shipped into the city from as far away as Newark, N.J., consigned here to syndicate operators under fictitious names. The alcohol then was distributed to several stills maintained by the syndicate on farms in Edina, Mendota, Crystal and Plymouth townships, where it was redistilled, rectified and purified and later sold in wholesale and retail lots.”

THE MURDER OF CONRAD ALTHEN

Conrad “Con” Althen, one of the men under indictment, was murdered at about 10:30 pm on Monday, December 18, 1933. His body was found in a ditch along Highway 19 in Dakota County, not far from Rosemount. It was riddled with 14 bullets from a machine gun. Dakota County District Attorney Harold Stassen was in charge of the investigation. An article dated December 21 said that Althen’s wife failed to shed any light on the slaying, and that prosecutors thought that the hit had been engineered by gangsters from out of town, possibly Chicago.

Althen was the Syndicate’s auditor and “fixer,” responsible for contacting the farmers and renting their barns and cellars. The FBI speculated that he knew too much and was about to squeal on the Syndicate. Another account said that he had already furnished the government with information. Yet another story was that he had tried to blackmail members of the Syndicate. After his death account books were seized from his home. Yet another account says that a “little black book” was found on Althen’s body and seized by the IRS. The FBI suspected that Tommy was responsible for Althen’s murder. During Banks’ 1959 civil trial, he disavowed any knowledge of Con Althen.

Because of Althen’s murder, the FBI and the U.S. Marshal’s Service stepped in to assist in the apprehension of the men under indictment. After two weeks, only four of the men had turned themselves in, and immediately posted bond. Althen himself had been pursued by two federal agents in Minneapolis at the end of November 1933, and they nearly cornered him on Portland Ave.

Althen had been the manager and golf pro at the Minnepau Golf Club, on Cleveland and Larpenteur Avenues in St. Paul. By 1933 the golf club had become the University of Minnesota Recreation Field. In 1921 Althen was among the first to inaugurate the “pay as you play” plan in 1921. In November 1930 he was convicted of a liquor charge and sentenced to six months in jail. In 1926 he was also indicted for auto theft but was acquitted, testifying that he did not know the cars and accessories police found on him were stolen.

After his death, police tried to trace four phone calls received at the the South St. Paul mortuary from women asking for the identity of the dead man.

On December 21, 1933, Max Stearns, Kid Cann, and Barney Berman posted $5,000 bond, reduced from an original $10,000 each. Tommy and another man, Bruno Franzmeier, surrendered to police on December 22, 1933. The case was continued to March 1, 1934. By that time the number of men indicted was 22.

GUILTY PLEAS

Although the Government had 61 witnesses lined up, many had memories that had become “hazy,” some who were “attempting to beg off from testifying,” and some “who have given certain statements under oat that have since ‘backed up’ on their testimony.” Some witnesses were other bootleggers from Minnesota and North Dakota who were understandably reluctant to testify.

Given the weakening government case, on March 13, 1934, a deal was struck with the seven “ringleaders.” They pleaded guilty, “apparently fearing an expose on the ramifications of the Minneapolis alcohol syndicate.” Those pleading guilty were:

- Tommy Banks, identified in the press as the Syndicate Leader, was fined $2,000. He told Judge Gunnar H. Nordbye that his occupation was whisky salesman.

- Max “Brownie” Stearns, fined $1,500. He ran a clothing store on Washington Ave. and had been released from Leavenworth four months ago.

- Peter Valder, alias Pete Hackett, Banks’ driver and handy man, fined $1,000. Valder said he had previously served a six-month jail term for bootlegging. An undated article indicated that at some point Hackett had been shot, and detectives questioned Tommy Banks, David Berman, and Charles berman to see if they knew anything that would help the police, but of course they did not. In fact, neither did Hackett, who was described as a “minor police character.” Police had heard reports that Pete had been “shooting off his mouth lately” and that racketeers were feuding about control of gambling spots downtown. Without a date it’s difficult to follow up.

- Clifford “Cliff” Skelly, fined $1,000. Skelly said he was in the poultry business and had been fined for a liquor law violation in 1931. Skelly had been sentenced to five years in Leavenworth for his part in the July 22, 1933, kidnapping of Charles F. Urschel and was out pending appeal.

- Max “Motley” Berman, fined $500 for possessing counterfeit Internal Revenue “strip” stamps. Berman claimed his previous record was clean.

- Kid Cann, sentenced to one year in the county jail and granted a stay of 30 days. He reported that he was unemployed, and had once paid a $1,500 fine. He was immediately granted a 30-day stay before he had to begin serving his sentence.

- Edward “Barney” Berman, sentenced to a year and a day at Leavenworth Prison. Berman said he was in the car radio business and had paid a $400 fine on a liquor charge nine years ago. Berman was also convicted in the Urschel kidnapping, sentenced to a year and a day in Leavenworth. He was immediately granted a 30-day stay before he had to begin serving his sentence.

The group’s lawyer, Archibald “Archie” Milton Cary, Sr. paid the fines immediately after sentencing, “taking a huge roll of bills from his pocket. The fines were paid in bills ranging from $5 to $100.”

The other 15 men were released as “small fry” in the organization. Their involvement included renting their barns or garages to the bootleggers, keeping the stills going, and delivering the goods. Four of the men were already in prison for unloading 4,400 gallons of alcohol on April 27, 1933, from a freight car in the Minneapolis, Northfield & Southern yards at 11th Street and Holden Avenue. The deal was reached because several witnesses had changed their minds about testifying against syndicate members. Bootleggers from Minnesota and North Dakota were also reluctant to testify. Those released included:

- Austin Cravath was a “fixer” who found farmers who would rent property for stills.

- Allan Pollock was a farmer who rented the Syndicate a barn where a still was used for about four days.

- Earl C. Nelson was a farmer who rented the Syndicate a garage which was used for 20 or 25 days.

- Emil Isaacson

- George Somers, alias Harry Halloran – possibly a fictitious character

- Benny Binder

- Roland Legacy, alias Charles Mathews, alias Goldberg

- William B. Hess, alias Billy Boardman

- Eugene Kretzke

- Roy Rogers, alias Floyd *

- Eddie Isaacson, alias Edward Kraemer, alias Edward Ward

- Andrew Carlstom, alias Pinky *

- Victor Wallace, alias Vic *

- Sam Cook

- Albert Berman

- Edward Kraemer

* These four men were brought to court from Leavenworth and Chillicothe Federal prisons, where they were serving time for the freight car incident.

The 1929 and 1934 convictions for bootlegging made Tommy Banks ineligible to hold a liquor license or own a bar. In 1954 Tommy remarked, “I had stuck my nose into the bootleg racket in the late ’20s and early ’30s and got two fines which was the only trouble I was in.”

MURDER AT THE CASABLANCA

On Friday morning, July 27, 1945, labor leader Albert Schneider, age 37, was killed by four gunshots in a shootout at the Casablanca Night Club, 408 Hennepin Ave. Schneider was an organizer for the General Drivers Union 544, AFL. Wayne Saunders (nee Rubin Shetsky), 39, the proprietor of the Casablanca, was charged with second degree murder. Banks was at the bar at the time of the shooting and was wanted for questioning. After the shooting Banks fled to his room at the Dyckman and then went “on the lam.”

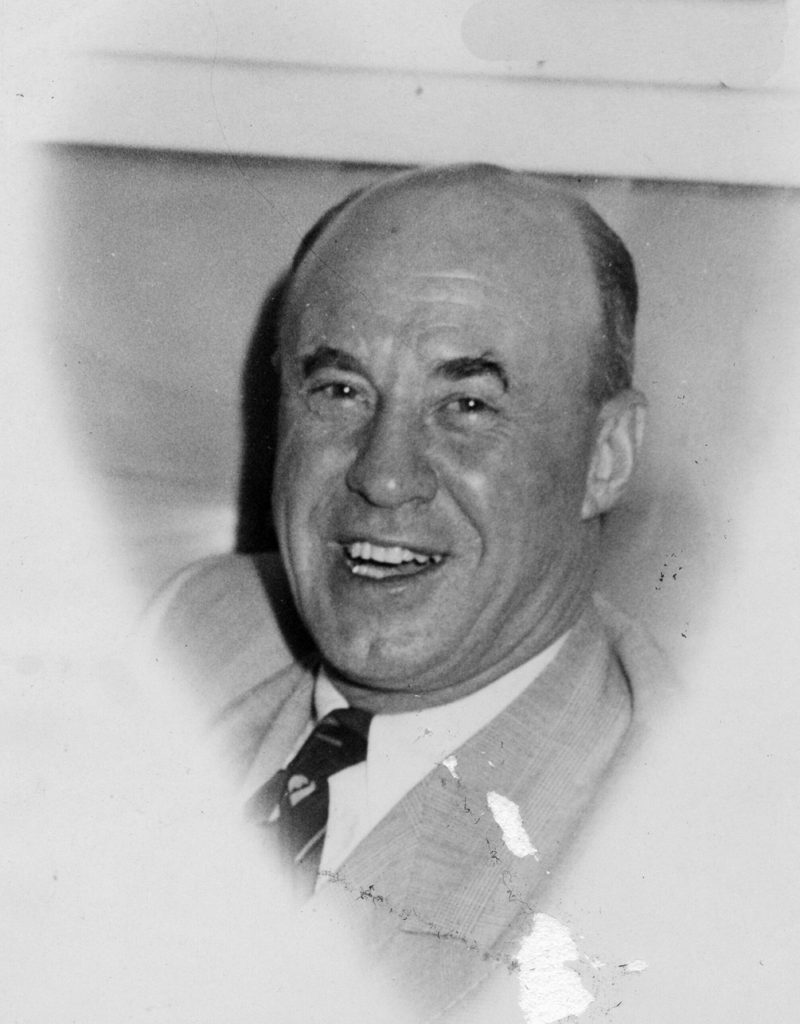

While he was thinking things through, the local papers told of his rise from a bellboy to a powerful underworld figure, “reported to be worth $400,000 to $500,000.” (Another article estimate his wealth as between $500,000 to $1 million.) He was also dubbed “Soft Touch Tommy” for his willingness to help out his friends with significant loans. As to his ownership of night spots, “A member of the liquor industry said Banks owns or has a share in, about 20 cafes or night clubs, or has in the past. They include some of the best known in town. But city and county records fail to show him listed as owner of any of the places.”

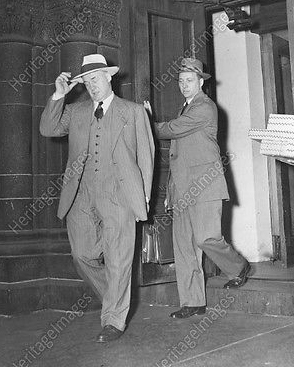

After three days, on July 30, 1945, he did come in to answer questions. The Tribune reported:

Banks gave his version of the events that led to the shooting. Saunders, Banks said, had attempted to persuade Schneider to leave the café after the closing hour, but Schneider refused. Banks said he kidded Schneider about his straw hat, then took Schneider’s hat and tossed it away. It landed on the floor and Schneider grabbed Banks’ hat and sailed it back of the bar.

Schneider then demanded that Banks buy him a new hat.

“Why should I?” Banks said he responded.

Saunders then intervened and again attempted to eject Schneider. Banks said Schneider struck Saunders in the side of the head and Saunders fell to the floor. Then shooting began. Banks said in the melee that resulted he was struck in the face and knocked to the floor.

Banks was vague in his statement as to details of the shooting. He said he did not actually see the shots fired. In the excitement he fled to the street with the others and thought the fight was continued outside, he said.

When he returned to sign the typed statement later that night, he had his first ever picture taken by a newspaper photographer – in this case, by Ted Miller of the Minneapolis Tribune.

Banks was never implicated in the murder.

Another witness was Fred Snyder, the victim’s brother and fellow union organizer, who named Shetsky as the man who killed his brother after an argument.

Shetsky was indicted on charges of second degree murder by the Hennepin County grand jury on August 1, 1945. He was initially denied bail until his trial, which was set for August 23, 1945. Attorney Archie Cary successfully got him a reversal, and he was let out on bail, which he jumped. It was disclosed in 1952 that four people posted the $20,000 bond:

- Herman Mitch, formerly of Casablanca, Inc.: $5,000

- G. “Mickey” O’Connor: $5,000

- A. Berenson, formerly of Jack’s Restaurant: $5,000

- Tommy Banks: $5,400 (through attorney Cary)

Attorney Cary tried to delay the trial to late September, claiming that he had hay fever at that time of year, but “Judge Carroll disregarded the hay fever plea.” Banks testified at the trial in 1947. Shetsky was first convicted and later acquitted for the shooting

The shooting came up again during Banks’s civil tax evasion trial in 1959. Shetsky was in an Oklahoma prison doing an eight-year sentence for a $30,000 fur burglary. He was brought to Minnesota for the trial. Banks re-enacted the shooting, and denied that Shetsky shot Schneider in order to save Banks’s life. “Banks testified that he had had no part of an argument that preceded the slaying, but that he had been knocked unconscious by Schneider’s brother.”

TAX FRAUD

Like Al Capone, Tommy’s downfall was not due to violence or even his nefarious activities per se but for tax fraud.

In 1934, at the end of Prohibition, Banks said that he became a part owner and $100/week salesman for the Old Peoria Liquor Co. It was only then that he began to file income tax returns.

Q: Hadn’t you known about the income tax laws before?

A: Yes.

Q: Why didn’t you file?

A: Because I had been in the whisky business. It would have been like putting a finger on yourself.

1937

In 1937 the government began “rounding up all former bootleggers and levying income tax assessments against them.”

In a preliminary report dated February 17, 1937, IRS Special Agent Peter V. Masica recommended prosecution for tax evasion for the year 1930, but the recommendation was not approved in Washington. A claim was made for $33,500 for the years 1920 to 1934. On July 26, 1937, Masica accepted a settlement of $5,727.56. This deal was hammered out with Banks’s attorney, Joseph O’Gordon, who was from St. Louis Park. O’Gordon was described in a 1959: “O’Gordon personifies the suave, smooth sharp-as-a-razor legal counsel who brought the word ‘mouthpiece’ into use 30 years ago.”

Tommy had filed a statement that suggested that he was insolvent and did not disclose that he had more than $300,000 in cash hidden in a 3 ft. high trunk in his basement. In about 1936 he had a floor vault built into a closet of his house. His explanation for his supposed insolvency was that he had made nearly $305,000 in loans but had no assurance that they would be repaid. He accepted no collateral and kept no records. That the loans were eventually repaid explained his net worth of more than $300,000 by 1947, he explained.

In the 1940 Census his occupation was listed as proprietor, W. Liquor. (Wholesale?) He reported $50,000 in income. On his World War II draft registration card he wrote that he worked at the Flour city Body Works, 2945 Blaisdell, Minneapolis. Curiously, he listed the name of the person “who will always know your address” as his sister Grace Shick in California, and not his wife Reta.

A memo by IRS Special Agent George H. McKusick from 1954 includes this nebulous charge about an operation that must have taken place in the 1940s:

The investigation disclosed an undercover participation by Banks in a black market liquor business, but since the whole venture was started and terminated within a calendar year, it was not incorporated in the net worth investigation which considered only year-end balances. The venture was terminated by a raid by the Alcohol Tax Unit, and criminal and civil liabilities were both borne by the “front” individual who operated it. The investigation disclosed that a pharmacy, from which Banks reported income, was in fact a bootlegging venture by which after-hour bottle sales were made to swing-shift war workers and taxicab drivers.

1950

In 1950 the IRS came after Banks for back taxes from 1937 to 1948. But because of the Statute of Limitations, the government could only prosecute in the criminal courts for 1945 to 1947. Tommy sought the advice of Hiram Z. Mendow, a criminal defense attorney. Mendow advised Banks to settle, and speculated that he could get the charges dismissed for $15,000. Banks ignored the advice and hired another attorney.

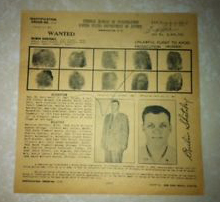

Banks was indicted by a Federal grand jury on January 14, 1952. The charge was “attempting to defeat and evade a large part of the income tax due and owing by him to the United States of America for the calendar years 1945, 1946, and 1947 as set forth in each of the three counts of the indictment in violation of Title 26, Section 145(b) U.S. Code. The Tribune reported that the grand jury “acted with speed that amazed even veteran courthouse employees.” The jury was called into session at 10 am to receive instructions from Judge Dennis Donovan and it started hearing testimony from IRS agents at 10:30 am. At 11:30 am the jury sent word to the court that it was ready to make a partial report. The indictment was handed down at 11:45 and a bench warrant for Bank’s arrest was issued immediately. He was allowed to surrender on his own at 2:00 pm, but didn’t show up until 5:00. “Terrible driving” was his excuse.

He was immediately released on $20,000 bond and told to appear again on January 28, 1952, when the bond needed to be renewed.

The trial lasted the better part of two weeks. The prosecutor was Miles W. Lord, assistant district attorney. John W. Graff, former U.S. district attorney in Minnesota, was the head of Banks’ legal team. A key witness was Banks’s accountant, Leonard H. Weinstock, who had prepared all of Tommy’s income tax returns since 1942, as well as records and returns for many of his business ventures. Unfortunately, Weinstock’s memory on key points was faulty, and no one seemed to know where most of the records – such as they were – were located. Perhaps they were with Harry Shepard, who was successfully avoiding being served a subpoena for the trial.

In his final arguments, Lord said that since Banks kept no books, the IRS was “forced to go in the back door” to get at the facts, and presented a chart that showed the difference between Banks’ “net worth” income and the amount he reported to the government. During the trial, the government removed from evidence Bank’ tax returns for the years 1948 – 1951, reducing the amount claimed to be owed to the government from $42,000 to $32,000.

Graff described Lord’s chart as a “monument of confusion – a monument of governmental stupidity.” Regarding the reduction in the amount owed, Graff remarked “If the trial had continued, maybe the government would owe Banks money.” Trial Judge Robert C. Bell told the jury that the amount didn’t matter: “It is sufficient if any substantial portion of the tax was attempted to be defeated and evaded as charged.”

The all-male jury was sequestered at the Lowry Hotel. After deliberating for just one hour and 50 minutes, on May 30, 1952, the jury retired a verdict of guilty on three counts of failing to pay approximately $32,000 in federal income taxes for the years 1945 to 1947. Banks showed no emotion when the verdict was announced. He was released on $20,000 bond the next day.

On June 23, 1952, Banks was sentenced to three years in prison and a $10,000 fine. A motion for a new trial was presented and overruled.

On July 9, 1952, Banks filed an appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.

On September 10, 1952, Banks filed a motion for an order modifying the sentence, suspending the sentence, or, if that didn’t fly, for probation. It was overruled on September 26, 1952. U.S. District Judge Robert C. Bell took the extraordinary step of withdrawing that decision and replacing it with a strongly-worded decision on October 20, 1952. Bell cited Banks’s unprofessional business practices, his lack of cooperation, his involvement in the Casablanca murder, the quality of his legal defense, and the sequestered jury when he made the decision that “the defendant is not the type of person who would be influenced or who would profit by the supervision of a probation officer. To extend probation in this case would be an abuse of the court’s power.” Judge Bell also said that the motion more than sixty days after the sentence, thus too late.

The U.S. Court of Appeals in St. Louis affirmed the conviction on May 27, 1953. [November 1, 1953]

LEAVENWORTH

Tommy eventually did serve three years in Leavenworth, but because of his appeals, it was kind of a revolving door.

He was due to begin his sentence on December 4, 1953, but was granted a stay until December 29, 1953, so he could have Christmas with his family.

On December 29, 1953, he surrendered to U.S. Marshall Enard Erickson at Erickson’s office in St. Paul. With him were his attorneys, Archie Cary and John W. Graff. Erickson handcuffed Banks to his left hand and took him to the Ramsey county jail. Ten minutes later he was on his way to Leavenworth to serve out the rest of his sentence.

A document dated January 5, 1954, related to his possible parole, characterizes Banks as “one of the two biggest racketeers in the Twin City area,” and “not the employee type.” He was “a hardened law violator,” not considered that he is a likely prospect for rehabilitation for parole.”

In January 1954 a list of approved correspondents and visitors included his parents (both listed but both dead), his brothers and sisters, wife Reta, and the following “friends:”

- Jerry Murphy, manager of McCarthy’s Restaurant

- Phill Broncheau, a banker in Minneapolis

- Bill Stearn, a banker in Fargo

- B. Brambilla

- Elmer Olson, owner of a boat business

- Charles Holleran, partner in McCarthy’s and the Blue Goose

He served six months in prison but on July 6, 1954, he was released on bond. pending possible review of his conviction by the U.S. Supreme Court. That review was denied and the case was referred back to the U.S. Court of Appeals for a rehearing in that court. That court reheard the matter at its March 1954 term.

On May 11, 1956, he returned to Leavenworth.

On June 29, 1955, the court again affirmed the conviction.

On April 18, 1956, Banks filed a motion in U.S. District Court to suspend the execution of his sentence and place him on probation and to reduce the sentence.

A May 25, 1956, prison document indicates that he was eligible for parole on October 30, 1956. The progress report says:

He states that when he is released from this institution he will reunite with his wife and he will again assume management of the Power Brake Equipment Co. which he owns. Banks made a very good adjustment when he was here before and has asked that he be considered for work in the Fire Station. He is expected to make a good adjustment when he is released from this institution, as he now has paying capital nought to operate a legitimate business and will not have to revert to illegal enterprises.

A December 17, 1956, memo indicates that Banks requested a transfer to a camp in Florence. The request was denied: “In view of [his residence in Minneapolis] and the notoriety in his case the Committee agreed that he does not qualify for transfer to a Camp.”

On March 27, 1957, he was released on bond when he requested a rehearing by the U.S. Circuit court of appeals at St. Louis. The court refused to rehear the case.

He returned to Leavenworth on June 25, 1957. He was assigned to the library, working as a card sorter and taking a course in library management. He earned ten days meritorious good timeHe went to chapel regularly. He was visited by his wife four times and corresponded with a brother and sister.

He was finally released for good at 9 AM on May 1, 1958, and returned to his home “by private transportation.” He was on conditional release supervision until August 1, 1958. His probation officer was Ernest J. Meili. A document in his file shows that the FBI wanted to be notified when he was released. The letter to the FBI was addressed to W. Mark Felt, Special Agent in Charge in Kansas City. Mark Felt would turn out to be “Deep Throat” in the Watergate scandal.

1959

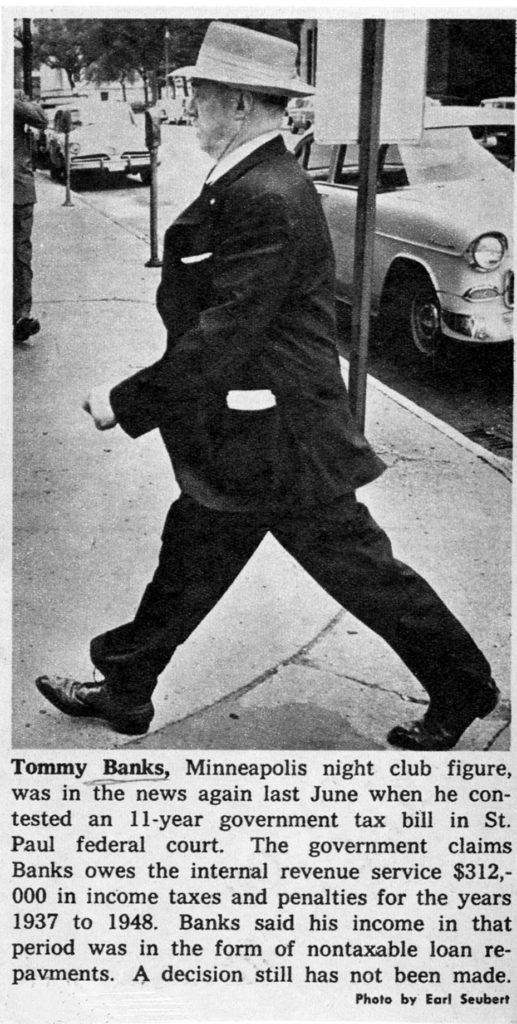

In 1959 the IRS again went after Banks for the back taxes in a civil suit, this time for the years 1937 to 1948. The amount they sought to collect was $312,000 plus interest. Banks claimed that much of the income came from repaid loans, which is not considered taxable income.

The proceedings were held before Judge Morton Fisher of Washington. He kept having to ask for the spellings of names, saying he wasn’t “familiar with your local situation.” The prosecutor was Thomas A. Steele, Jr. Miles Lord, by now Attorney General, was called as a witness.

The judge tried to call Harry Shepard as a witness, but Phillip J. Stern, his attorney, said that Shepard had “suffered at least three strokes of apoplexy in the past two years and would not make a competent witness.” His physician, Dr. George C. Dorsey, testified that Shepard had a serious illness in October 1956 and that he was suffering from “confusion, disorientation, brain atrophy, loss of memory and a slur of speech.” Furthermore, if forced to testify, it “could cause a cerebral hemorrhage or other serious results.” Judge Fisher ruled that Shepard would be required to testify, even if the judge had to go to his house. As to the assertion that Shepard would likely provide “misinformation” to the court, Fisher said, “Sometimes in the administration of justice certain risks must be taken.” Shepard was famous for “subpoena-ducking by pretending illness or leaving town,” according to prosecutor Thomas A. Steele, Jr.

1961

By the time Judge Fisher issued his ruling in August 1961, the amount Tommy owed grew to $590,000, including $195,000 in delinquent taxes, $98,000 in fraud penalties, plus 6 percent for each year the taxes went unpaid. The government established his net worth as of December 31, 1947, as $400,000. An inventory of his assets had 62 separate items – see Holdings, below.

To secure its claim the IRS filed a lien against everything Banks owned in 1952.

1968

Apparently Tommy did not take the judge’s ruling seriously, and in July 1968 the Government filed suit to have the U.S. District Court foreclose on liens and mortgages for payment of back taxes in the amount of $314,558.23. Tommy still had a long list of assets.

Banks apparently settled the case; attorney Mendow was quoted as saying that Banks ended up paying over $1 million to the IRS.

HOLDINGS

On the books, Tommy officially only owned two pieces of property:

- His house at 3817 Drew Ave. So., Minneapolis, built in 1932, still standing. Banks bought this home before 1935.

- A farm, variously reported anywhere from 230 to 370 acres, in Dayton Township, two miles north of Champlin on West River Road. This may be the “Peterson Farm” that was mentioned by a friend in a 1952 interview.

Several properties were owned in the name of Tommy’s wife Reta. Reta stated that Tommy gave her $5,000 each Christmas, and that money was used to purchase her properties. During the 1959 civil tax trial, those properties were considered to belong to Tommy as well.

State statutes and city ordinances provide that no person may own more than one liquor license. In addition, Tommy had bootlegging convictions on his record. However, from the mid-1930s to the late 1950s, Banks was said to own shares of or have loaned money to the owners of the following businesses:

- The Alaskan Club in Seattle, Washington: Banks loaned Stanley Schultz $11,000 plus a $600 automobile and was paid back in 1945 when Schultz sold the club the same year. Schultz had been convicted of hijacking liquor in 1937.

- B&S Corp. owned the property at the Casanova. The address of the company was 105-107 So. Fifth Street (the First National-Soo Line Building), which was the office of attorney Simon Meshbesher. Incorporators of the company were Harry Shepard, Reta Banks, and Cera S. Meshbesher, who may have been Simon Meshbesher’s private secretary and/or sister (she was not his wife).

- Banks and Shepard, Inc., 1316 Nicollet Ave.

- Brady’s Bar, 604 Hennepin Ave. – Banks only admitted to loaning money “back and forth” to owner George Brady, who had changed his name to Harry Clark. This building was replaced in 2004.

- Brown Trailer and Hi-Way Trailer Business Company: This was a “jobber franchise for a number of house trailers which he delivers to dealers throughout the State of Minnesota.” This business was first noted in 1956.

- Budweiser Tavern Building, Savage, Minn.

- Camden Liquor Store, 4164 Washington Ave. No. – The building was owned by Earl A. Jeffords, one of the incorporators of McCarthy’s. Jeffords rented the Camden building to Jack R. Lally, a former police inspector. Jeffords built the building specifically for Lally’s store. The liquor license was approved despite a 1,200-name petition signed by North Side residents.

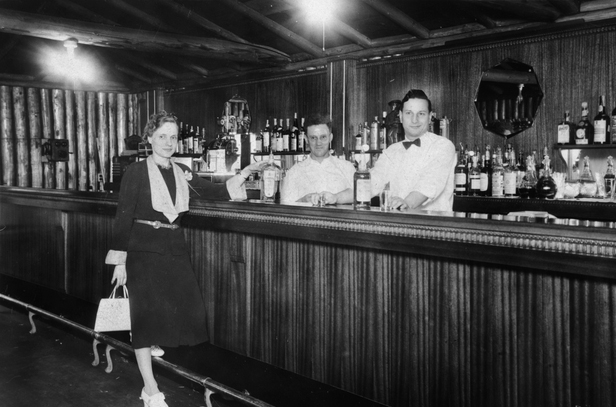

- The Casablanca Night Club,408 Hennepin Ave. (photo above). In 1952, the government said that that the shares were owned as follows:

- Banks: 90 shares ($7,800) under the name F.J. Wickers, an employee in his wheel service company.

- Herman Mitch: 34 shares

- Thomas P. Gleason: 56 shares.

A 1959 article says that Banks loaned Mitch $31,000; $15,000 to start the bar plus money Mitch owed him for bootleg alcohol. Not all of it was repaid. On August 3, 1945, William Donnelly deposited $20,000 in cash in the First Produce State bank and received a certified check for the same amount, presumably for the purchase of the Casablanca. When the Casablanca was sold to Toung-Poy and subsequently to A.B. Percansky for $42,500, Banks admitted receiving money.

- The Casanova Bar, located in the Kruze building, 43-45 So. Fourth Street. (Now 414 Nicollet Mall, the NSP Building, built in 1965) Banks and Shepard purchased the building on December 13, 1943, through attorney Simon Meshbesher, for $15,000. In 1947 the property was owned by Tommy and Reta Banks and was sold to the B&S Co. (See separate entry.) Tommy would only admit that in 1944 he had loaned $10,000 to Thomas E. Ewing, proprietor and holder of the liquor license. Ewing operated as President of Casanova Bar, Inc. In June 1959 Banks said that he, Shepard, and Reta recently sold the Kruze Building to the government.

- Coin-a-Matic Amusement Co., 1316-20 Nicollet Ave. Banks said the firm installed pinball machines and juke boxes. In July 1951 Banks and Shepard sold this building to Henry (Hy) Greenstein for $61,000. An article from January 1952 said that the building housed the Pioneer Distributing Corp and and a beauty parlor. The current 1300 Nicollet Mall was built in 1979.

- Daily Mail newspaper. According to Banks he gave $5,000 to Harry Shepard to invest but said “I don’t want to have anything to do with it.” Another partner was Len Welch, who resigned from the Minneapolis Star and Tribune on October 30, 1947, to publish the Mail. Welch did not recall receiving the $5,000 from Banks. Other partners Earl Almquist and Joe Summers similarly did not recall receiving the $5,000 payment from Banks.

- Flour City Body Corp., 2947 Blaisdell Ave. Dun and Bradstreet listed Archie Cary as President and Banks as Vice President. Banks was part owner until 1952; the company made van bodies. The property is now 30 W. Lake Street, built in 1977.

- A gambling place above Freddie’s Café, 605 Second Ave. So. Banks loaned money to owner Mickey O’Connor. In 1959 Mickey’s brother, Robert, testified at Banks’s tax trial that Robert would deliver cash repayments from Mickey to Banks periodically, usually to Brady’s Bar. The Freddie’s site is now 201 Sixth Street So., built in 1990.

- Hungry Jack Lodge, Grand Marais, Lake Superior National Forest. Tommy owned a cabin on the lake near the Gun Flint Trail. Reta Banks claimed in 1959 that the property belonged to her, not Tommy.

- The Kentucky Club, a/k/a The 318 Club, was a gambling house at 318 Nicollet Ave. that opened in 1941. In 1943 Banks held a quarter interest under the name of Michael “Mickey” O’Connor, who owned 10 percent of the club himself. In 1952 Banks testified that in 1944 he had a 12 ½ percent interest in the club. The club was run by Jack Bortz, a/k/a Jack Doyle, who owned Jack’s Restaurant, another gambling house. Bortz asserted that the Kentucky Club was having trouble with the police in 1943, but after Tommy bought an interest in it, the trouble stopped. Another partner was Phillip (Flippy) Share, Bortz’s brother-in-law. In 1959 Banks testified that his proceeds from the club were delivered to him once a month by O’Connor. Mickey’s brother, Robert, testified that he would deliver cash repayments from Mickey to Banks periodically, usually to Brady’s Bar. The club was closed down in 1945 and the site is now the Hennepin County Central Library. Mickey died in 1947.

- Koolaire, Inc.

- Liquor store on South 5th Street in Minneapolis – Banks loaned $15,000 to James B. Carlson in the 1930s but Carlson went blind and the business went bankrupt but Banks said the loan was repaid.

- Liquor store at 2 No. Third Street, run by Jessie Beshears, 2002 Pillsbury Ave. Banks said he advanced one-third of the tax liability of the store but denied having any interest in the store, which was financed by Harry Shepard.

- McCarthy’s Café was incorporated on March 18, 1942, by Tommy Banks, Keith D. McCarthy, and Earl A. Jeffords. (Click on the link for the history of McCarthy’s.) On October 27, 1950, there was a change in directors and stockholders:

- Jeremiah Murphy was President and Director

- Reta Banks was Secretary, Treasurer, and Director

- Harry H. Clark was a Director

Shareholders were:

- Reta Banks: 110 shares

- Harry Clark: 110 shares

- James J. Keefe: 82 1/2 shares

- Harry Shepard: 27 1/2 shares

Tommy was the hands-on proprietor of McCarthy’s, with the assistance of Manager Jerry Murphy. Liquor Manager Glenn C. McArthur remembers his strange interview with Tommy and his experiences working with him at McCarthy’s. Tommy sold McCarthy’s in early 1968.

- The Mill Pond in Shakopee. Banks loaned money to Mickey O’Connor to establish this gambling spot. In 1959 Mickey’s brother, Robert, testified at Banks’s tax trial that Robert would deliver cash repayments from Mickey to Banks periodically, usually to Brady’s Bar.

- The Mohawk Liquor Co. – Banks held stock under the name of Archie Cary.

- Music Installations, Inc., 1316 Nicollet (1300 Nicollet Mall) – in partnership with Harry Shepard

- National Plastics Corp. and National Sound Corp., New York – Banks sold his 50 percent interest in both companies to his attorney, Archie Cary, on January 10, 1946, for $25,000.

- Northwest Novelty Co., 2329 W. Broadway – Banks testified that he had invested in the firm, but Edward Schoen, owner, told the Tribune that he was the sole owner since it was founded in 1943 and denied any connection to Banks.

- Old Peoria Liquor Co. – he said that he became part owner and $100/week salesman in 1934. This building, built in 1928, still stands.

- Oneida Building, S. 4th Street and Marquette Ave. Howard Gelb, a former U.S. assistant district attorney, said that he and two associates purchased the building through an agent who represented Banks in about 1949. Although Banks was the owner of the building, Gelb said that he never met him and did notknow that Banks owned the property. In 1960 a new building was built on the site (address changed to 110 Fourth Street So.)

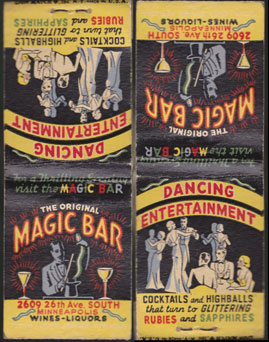

- Original Magic Bar, 2609 So. 26th Ave. So. – Reta’s brother bought 247 shares of stock on December 1, 1944; Tommy denied having any interest in it. The building burned down and was replaced in 1989 – it now the New French Bakery.

- The Oriole Apartments, 224 So. Tenth Street – On April 10, 1946, Harry H. Clark and Banks purchased the building from the S.T. McKnight Co. for $42,000. $22,500 of this amount came from a loan from the Sons of Norway, and Banks advanced half of the remaining $19,500. That entire street is now vacant (2016)

- Pearson News Service, in the former Andrus building at 512 Nicollet. Banks claimed a 10 percent interest. This was “an agency that made book on baseball, football and basketball” according to Banks. The building, now 500 Nicollet Mall, is still there – built in 1898.

- Phoenix Drug Store: See Quality Pharmacy, below.

- Power Brake and Equipment Co., 2417 University Ave., St. Paul – in partnership with attorney Archie Cary. Frederick J. Wickers was President of the company. Banks started the company in about 1945.

- Quality Pharmacy, 3rd and Hennepin – operator Ferdinand Hollen (alias Fred Holland) admitted that in 1943 and 1944 the drug store sold liquor after hours. In 1952 the government charged that Banks and Harry Shepard had each advanced $7,500 to Hollen and both made income tax reports of 25 percent of the profits. Banks disavowed any knowledge of having ownership of the store and said that Shepard must have made the investment.

- Ring Construction

- Tenth Street Realty Co.

- Wheel Service

- Wickers, Bans and Abb, a St. Paul truck and trailer equipment firm

- 114 Club. On November 1, 1942, Coinamatic (see above)paid $3,543.17 to L.G. Brouillard, who bought the bar from Estelle O’Neil. Banks admitted he had a half interest in the transaction.

- 614-616 Third Ave. So. In 1943 Tommy’s wife Reta put a $1,000 down payment on the building, where a second floor gambling room was owned and operated by Robert B. Hamilton. In 1952 Banks explained that the money was a loan to Earl Jeffords. The site is now the Hennepin County Government Center, 300 Sixth Street So., built in 1979.

- 3952 Beard Ave. So. (built in 1931, still standing)

- 4400 E. Lake Street (Commercial building built in 1949; renumbered as 2949 44th Ave So.)

- 5238 Excelsior Blvd., St. Louis Park (built in the 1930s, since removed)

THE BLUE GOOSE

The Blue Goose Inn is a resort located in Garrison, Minnesota, on Lake Mille Lacs. The Inn had been built by a man named Ferguson from Duluth in about 1922-23.

Ferguson’s daughter, Margie Cooper, ran the Inn until she died in the spring of 1926. The E.H. Perry family took over management until 1937, when George Howard Crosby became the new owner.

Crosby got the Inn a liquor license, and until 1947, when Governor Luther Youngdahl waged a war on slot machines, the Blue Goose was popular for this legal form of gambling. The resort was supposedly frequented by such luminaries as Al Capone and Clark Gable.

Doug Grow, in an article written when the Blue Goose burned down, wrote “It was owned into the 1970s by Tommy Banks pr Banks’ family members.”

The incorporators of record were:

- Charles Holleran

- Reta Banks

- Mark J. McCabe of Minneapolis – also an incorporator of Brady’s Bar

The building burned down on March 6, 1993 – a disgruntled customer named Vincent Luschen admitted that he had set the fire after being kicked out of the place for causing trouble. At the time it belonged to a bank following a bankruptcy and was about to be purchased by Mark Tadych, Bob Tadych, Ken Toso and Ron Lingwall. The Blue Goose has since been rebuilt.

GARDENA, CALIFORNIA

In 1949 Banks was in California for a vacation and met up with Hardy G. Lee, brother of Tommy’s wife Reta. Lee had a chance to lease a poker club license, but had no money for a building. Banks persuaded many of his friends to join him in raising capital for what became the Horseshoe Poker Club, located in a small enclave of Los Angeles called Gardena. A corporation called the Val Cranz Corp. was created to own the building and then rented it to Lee. Investors included:

- Tommy Banks: 750 shares

- Harry Shepard: 500 shares

- Charles Holleran, an incorporator of the the Blue Goose in Garrison, Minn.: 250 shares

- Nathan Shapiro, Minneapolis: 168 shares

- Rose Shapiro, Minneapolis: 166 shares

- Adelle Shapiro, Minneapolis: 166 shares

- Harry H. Clark: 750 shares

- Pearl Palm: 250 shares

- Bo Herbert: 750 shares

- Jack Hecht, Minneapolis: 750 shares. When Hecht died in October 1949, his shares went to Jack Davenport and Phillip (Flippy) Share, both of Minneapolis. These shares were apparently sold on the open market, and one document indicates that they were sold to “some hoodlums.”

In an interview in 1952, Tommy described his efforts to make sure that the club was operated in a legitimate way:

In the ceiling of the place there were “peep holes” so that it was possible to watch every game. If a gambler was observed cheating he was tossed out of the place. On the first night the place was opened, 17 players were kicked out of the place. On the second night, 14 players were evicted and after that there was little cheating. The players were charged 25 cents per chair for 20 minutes playing and there were eight persons at a table. For higher stakes the fee was 50 cents per 20 minutes. They had to pay a license of $750 per annum per table and another $3,000 license. The latter is used to build playgrounds for the children of Gardena, California.

USA Confidential charged that proceeds from the club were used to fund corrupt political campaigns. (There is nothing on the Internet that suggests this era in Gardena history.) Another document repeats rumors that “strip poker” was legal in Gardena, and that there were similar clubs in the town. When Tommy sold out his interest, Lee retired and sold real estate part time.

STREET CAR FRAUD

In October 1950 the Minnesota Railroad and Warehouse Commission launched an investigation of the Twin City Rapid Transit Co. The commission found that several people had bought stock in the company in an effort to gain control. The list included:

- Fred A. Ossanna, attorney and President of the TCRT: 1,200 shares

- Tommy Banks: 500 shares. Ossanna said that Banks sold his stock in late 1951.

- Tommy’s brother, Harry Banks, who owned a clothing store in Lincoln, Nebraska: 2,400 shares

- Kid Cann: 9,300 shares. Ossanna said that Cann sold his shares in October 1950.

- Lillian Blumenfeld, Kid Cann’s wife: 1,500 shares

- Harry H. Clark, Manager of Brady’s Bar

- Archie Cary, Banks’ attorney: 4,900 shares

- Harry Shepard: 3,000 shares

- Thomas Ewing: 1,300 shares

- Jeremiah Murphy, manager of McCarthy’s Restaurant: 1,000 shares

The story of the dismantling of the Twin City Rapid Transit Company is complex; Tommy survived the scandal unscathed, but Kid Cann, Fred Ossanna, and a scrap iron dealer named Isaacs were put on trial in Federal court. Cann was acquitted, but Ossanna and Isaacs went to jail.

THE END

Reta Lee Banks died on January 22, 1971 at age 74. The cause of death was an “acute myocardial infarction” – he had suffered from hypertension for the past five years. She was “entombed” at Sunset Memorial Park Cemetery in Minneapolis.

After Reta’s death Tommy had a long-term relationship with Thelma/Selma Anderson, but they never married.

Tommy Banks died on September 6, 1985, at age 91. He died at Abbott-Northwestern Hospital of congestive heart failure, after suffering from heart disease for the last 15 years. He had had a previous heart attack in November 1981. He is buried at Sunset Memorial Park Cemetery in Minneapolis.

Fun Postscript: Meredith McCarthy actually found one of Tommy’s hats and donated it to the St. Louis Park Historical Society!

CAST OF CHARACTERS

HARRY SHEPARD

Harry Shepard was born on June 11, 1893.

Mike Brey’s research shows that Harry and his wife, Vivian, each owned “soft drink” establishments in Minneapolis during the early 1920s. Harry was charged with a liquor violation in 1925 and paid a fine of $400.

In 1926 Harry was convicted of second degree murder of two people and sentenced to Stillwater State Prison for seven to ten years. Future Governor Floyd B. Olson was the prosecuting attorney, and mob lawyer Archie Cary was Shepard’s defense attorney. The case centered around an automobile crash on 12th and Nicollet, where a car occupied by Shepard and three other men ran into another car and killed the parents of a six-year-old girl, who survived. Harry and another of his passengers left the scene before the police came and then denied they were there.

Shepard was named in the 1951 Kefauver crime hearings as an associate of Banks in the Gardena, California gambling venture.

Shepard owned 25 acres of land in Champlin, Minnesota.

He died on November 19, 1960, in Golden Valley.

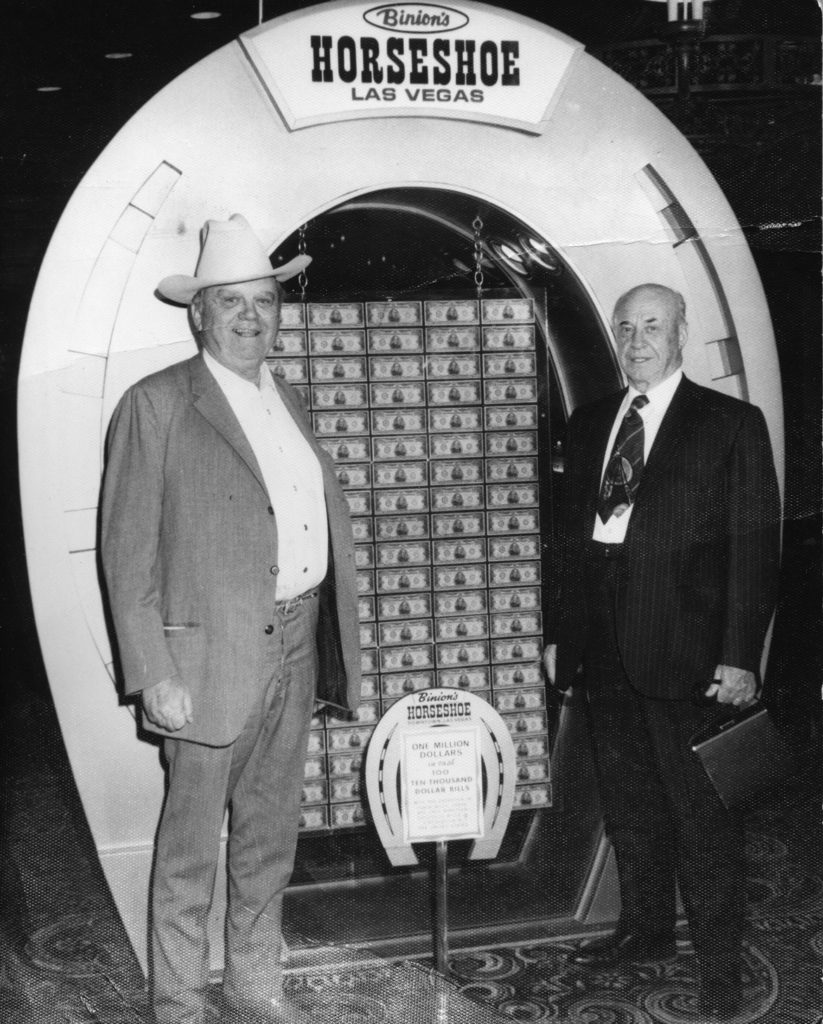

BENNY BINION

Chester Benjamin “Benny” Binion was a cellmate of Tommy’s. He is described as a “dirt-poor cowboy son of a Texas horse trader” who made his fortune gambling, despite the fact that he was illiterate. Tommy Banks tried to teach Benny his letters while they were in Leavenworth together, says Mike Brey. Benny owned his own Horseshoe Casino in Las Vegas, where he displayed $1 million in cash “to give people that pleasure.”

A 1958 memo to J. Edgar Hoover indicated that efforts were being made to cultivate Binion into an FBI informant. The memo revealed:

Binion related he was a close friend of Tom Banks. He stated Banks has very high blood pressure and had nose bleeding spells while they were both doing time at [Leavenworth]; he thought at times Banks would bleed to death.

The Minneapolis office [of the FBI] requested Binion be contacted relative to any new business acquirements of Banks since his release from Leavenworth in May 1957. Binion stated Banks had enough business connections to keep him busy, particularly the large brake and wheel factory there and the part ownership of some taverns in Minneapolis. Binion said he had invited Banks to visit Las Vegas when he was released from Leavenworth, but his health had apparently prevented him from traveling.

Binion laughingly remarked he received enough money as a result of the sale of the Horseshoe Club [in Las Vegas] and its related properties to pay up his tax debts to the U.S. Government, which would be between $200,000 and $250,000. It should be noted Binion was not supposed to have any interest in the operation of the Horseshoe Club, its being owned by Joe W. Brown, who had 97 1/2 percent, and R.R. Caudill, 2 1/2 percent.

[Binion] was convicted of income tax evasion and sentenced to five years. He has paid approximately $600,000 in fines. He was released from the penitentiary on March 19, 1957, on a writ and at the present time is out on bond. Binion is well known in Nevada and Texas as a top gambler and bootlegger. He operated in Dallas until 1947 when he came to Las Vegas to engage in legal gambling. Binion left Las Vegas June 9, 1958, to spend the summer on his ranch near Jordan, Montana. he made a statement that he expected Tom Banks of Minneapolis to visit him.

ARCHIBALD MILTON (A.M.) CARY, SR.

A.M. “Archie” Cary was Tommy’s lawyer. He was born in Wisconsin on January 16, 1881.

In 1910 he was living in a “Woman’s Boarding House” on 10th Street South – no doubt student’s quarters at the U.

In 1920 he and his wife Grace lived at 4741 Harriet Ave. in Minneapolis.

In 1930 his wife was listed as Marguerite.

Archie Cary died on February 16, 1959, and is buried at Lakewood.

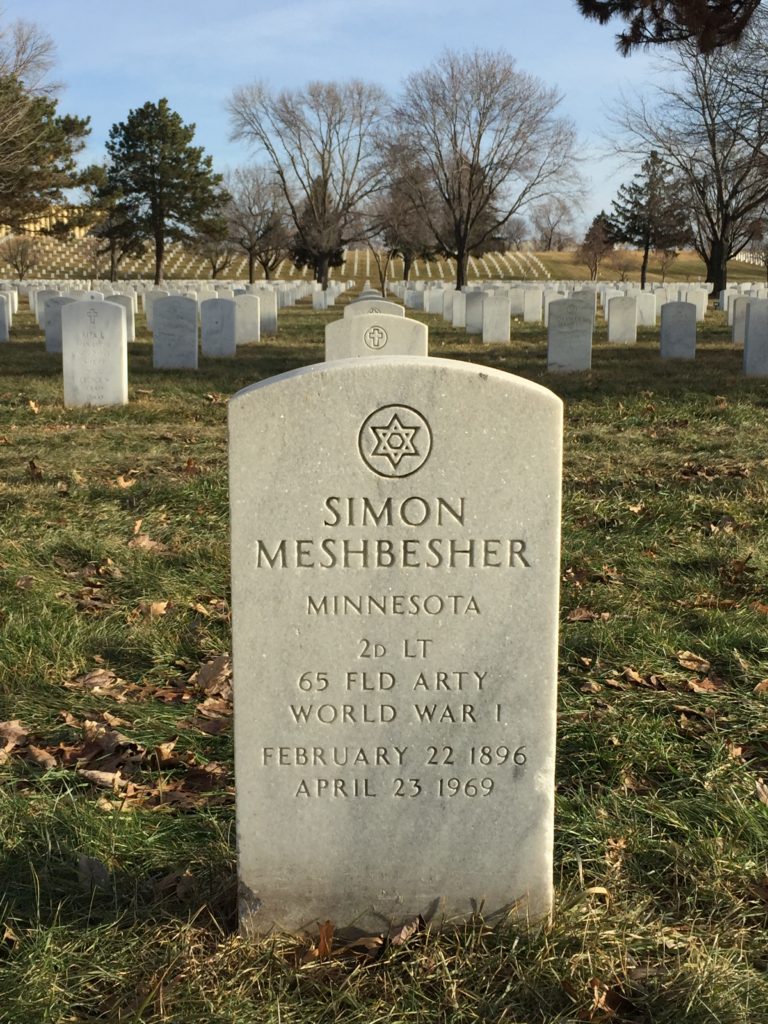

SIMON MESHBESHER

Simon Meshbesher was another attorney who worked for Tommy, usually in the context of his business dealings. In 1952, in an interview relating to Tommy’s tax trial, Meshbesher strongly defended Tommy and characterized him as a soft touch who freely loaned money to people but “does not know anything about bookkeeping and could not intelligently analyze a financial statement if his life depended on it.” Simon also objected to the way Tommy was vilified in the press and accused the Minneapolis Tribune of character assassination. Meshbesher insisted that he had never been asked to do anything unethical or “shady.”

Meshbesher was born on February 22, 1896, the son of Russian immigrants Jacob and Bessie Goldman Meshbesher. He served as Second Lieutenant during World War I. He died on April 23, 1969. Simon’s brother Nate also worked for Tommy Banks, according to Alan Weisman in his book Echo in my Blood. Nate is the father of famed local attorney Ron Meshbesher.

SOURCES:

Newspaper Articles

Minneapolis Tribune, December 20, 1933: “Roundup Ordered in Liquor Slaying – U.S. Will Push for Arrest of Ring Suspects”

Minneapolis Tribune, December 21, 1933: “Althen Killer Hunt Goes On”

Minneapolis Tribune, December 22, 1933: “Face Rum Conspiracy Charge”

Minneapolis Tribune, December 22, 1933: “Three More Give Bond in Liquor Case”

Minneapolis Tribune, December 23, 1933: “Two More Run Ring Suspects Surrender”

Minneapolis Star, March 13, 1934: “7 Plead Guilty in Rum Ring”

Minneapolis Tribune, March 14, 1934: “7 Plead Guilty in Liquor Ring”

Minneapolis Times, July 28, 1945: “Murder at the Casablanca” (editorial)

(Paper Unknown), July 28, 1945: “’Soft Touch’ Tommy ‘on Lam’ in Murder”

Minneapolis Times, July 28, 1945: “Silent Tommy Banks Got Start in Dry Era”

(Paper Unknown), July 30, 1945: “Banks Called to Tell Grand Jury Story of Slaying”

Minneapolis Tribune, July 31, 1945: “Police Hear Banks Version of Shooting in Casablanca”

Minneapolis Times, August 2, 1945: “Records Show Banks Owns But Two Pieces of Realty”

Minneapolis Morning Tribune, August 3, 1945: “Shetsky Bail Fight Opens”

(Paper Unknown), January 10, 1947: “Casanova Café Site is Sold”

(Paper Unknown, no date): “Tommy Banks Man Linked to Lally Site”

Minneapolis Tribune, June 19, 1950: “Tommy Banks Describes His Bootlegging in ’30s” by Jacqueline Adams

Minneapolis Tribune, January 15, 1952:

- “Tommy Banks Surrenders, Posts Bond on Tax Charge,” by Charles E. Benson.

- Photos of Horseshoe Club in Gardena, Harry Clark’s cabin cruiser, and room 1010 at the Dyckman Hotel

- “Banks Started as a Bellhop”

- Full text of IRS indictment

Minneapolis Tribune, February 15, 1952: “Tommy Banks Has Sold TCRT Stock: Ossanna,” by Edward Wicklund

Minneapolis Tribune, May 22, 1952: “Tommy Banks Posted $5,400 of Bail for Shetsky,” by Charles E. Benson

Minneapolis Tribune, May 25, 1952: “Banks’ Aid Has Lapse of Memory”

Minneapolis Star, May 31, 1952: “Banks Released on $20,000 Bail After Conviction”

Minneapolis Tribune, December 4, 1953: “Banks Wins Plea for Christmas at Home,” by Charles E. Benson

Minneapolis Tribune, December 29, 1953: “Banks Enters Leavenworth Prison Today,” by Charles E. Benson

Minneapolis Tribune, July 8, 1954: “Tommy Banks Back in City”

Minneapolis Tribune, July 28, 1955: “Tommy Banks Is Refused Rehearing”

Minneapolis Tribune, June 18, 1959: “Tommy Banks Used Phony Names U.S. Says as Tax Trial Begins,” by Jacqueline Adams

Minneapolis Star, June 18, 1959: “U.S. Calls Lord in Banks Trial,” by Larry Fitzmaurice

Minneapolis Star, June 19, 1959: “Banks Tells of Leaving Racket,” by Larry Fitzmaurice

Minneapolis Tribune, June 20, 1959: “Banks Says He Took No Notes on Loans,” by Jacqueline Adams

Minneapolis Star, June 22, 1959: “Banks Held Interest in Casablanca,” by Larry Fitzmaurice

Minneapolis Tribune, June 23, 1959: “Banks Tells Part in Gambling Sites,” by Jacqueline Adams

Minneapolis Star, June 23, 1959: “Banks on Stand for Fourth Day”

Minneapolis Star, June 26, 1959: “Banks’ Wife Claims Property Ownership”

Minneapolis Tribune, June 28, 1959: “Tommy Banks Loaned Thousands, Court Told,” by Jacqueline Adams

Minneapolis Tribune, June 28, 1959: “Was Banks Czar of the ‘40s in City?” by Jacqueline Adams

Minneapolis Star, June 19, 1959: “Gambling-Politics Link Aired at Banks Trial,” by Larry Fitzmaurice

Minneapolis Star, June 29, 1959: “Jury Told of Money Repaid to Banks,” by Larry Fitzmaurice

Minneapolis Tribune, 1959: “Banks Protected City Dice House, U.S. Agent Says,” by Jacqueline Adams

Minneapolis Star, August 19, 1961: “U.S. Says Tommy Banks Owes $590,000 – Interest is $60 a Day”

Minneapolis Tribune, July 12, 1968: “U.S. Sues Tommy Banks for Taxes”

Minneapolis Star and Tribune, September 12, 1985: “A legend from the city’s checkered past dies,” by Jim Klobuchar

Minneapolis Star, March 19, 1993: “Garrison’s Blue Goose may be cooked, but the Memories survive” by Doug Grow

Minneapolis Star, August 10, 1993: “A birthday bash, then it’s back to work – at age 100” by Doug Grow

Minneapolis Star, no date: “Las Vegas Hotelman Has Framed the First $Million He Earned”

Correspondence

Memo to Assistant Commissioner, Operations, IRS from Special Agent George H. McKusick, January 18, 1954

Memo to Michael F. Malone, Special Agent, from Harold B. Holt, Assistant Regional Commissioner, Intelligence, May 28, 1956

Memo to Record, Leavenworth Penitentiary, December 17, 1956

Letter to Special Agent W. Mark Felt, FBI Kansas City, from Leavenworth Penitentiary, May 1, 1958

Memo to Director, FBI from SAC, Salt Lake City, Re: Chester Benjamin Binion, dated November 5, 1958

Memo from Clifford Janes, Assistant U.S. Attorney, to Henry Kinney, Editor of the Broward Herald in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, dated June 29, 1955

Misc. Documents

U.S.A. vs. Thomas W. Banks: Order by U.S. District Judge Robert C. Bell, October 20, 1952

Interviews with Defendant and Witnesses: September 5, 1952 – Ernest J. Meili, Chief U.S. Probation Officer

Report on Convicted Prisoner by U.S. Attorney,” January 5, 1954

List of Approved Correspondents and Approved Visitors, Leavenworth Penitentiary, January 27, 1954

Admission Summary, Leavenworth Penitentiary, January 27, 1954

Special Progress Report, Leavenworth Penitentiary, July 1954

U.S.A. vs. Thomas W. Banks, U.S. District Court, District of Minnesota, Third Division, Order: April 24, 1956

Special Progress Report, Leavenworth Penitentiary, May 25, 1956

Sentence Data Record, U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons: June 26, 1957

List of Approved Correspondents and Approved Visitors, Leavenworth Penitentiary, July 10, 1957

Special Progress Report, Leavenworth Penitentiary, January 3, 1958

Memoir of George E. MacKinnon, October 9, 1992

Rotary Speech, George E. MacKinnon

USA Confidential, Jack Lait and Lee Mortimer, 1952