Believe it or not, St. Louis Park was on the cusp of being the site of a national baseball stadium. The first we heard of these ambitious plans came from an article published on December 17, 1948, in the St. Louis Park Dispatch. Here is the article in its entirety:

MILLERS PICK PARK FOR BASEBALL PARK, WILL CONSTRUCT ALL-PURPOSE STADIUM

An abandoned gravel pit in St. Louis Park is scheduled to become the site of a new ball park and all-sports stadium for the Minneapolis Millers.

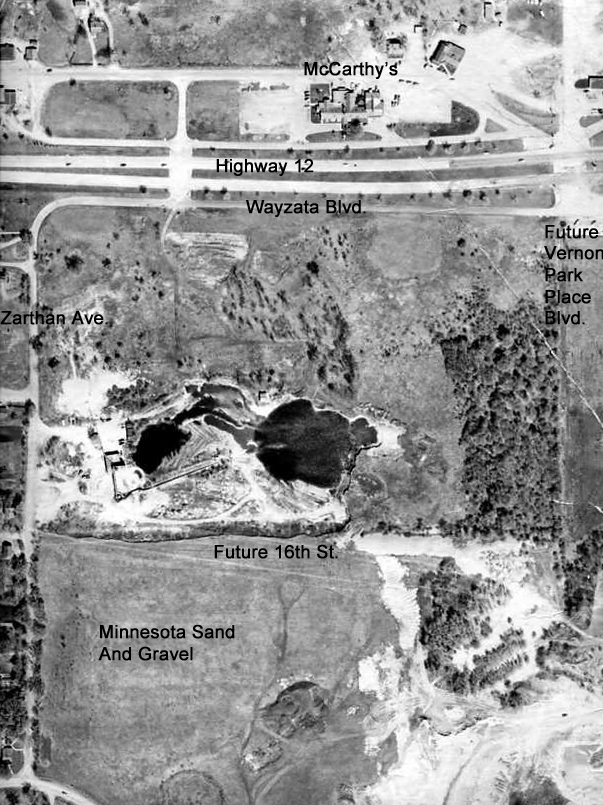

Location of the 20-acre tract of land is at Wayzata boulevard and Zarthan Ave. on the south side of the highway, approximately across the road from McCarthy’s cafe.

But before the stadium plans become an actuality, the new York Giants, owners of the Millers, must first secure village council approval of the project.

An application for rezoning from commercial development must be made and the council must approve building plans of the $1,500,000 ball park.

Announcement of the purchase of the Park property was made Monday by Horace Stoneham, president of the Giants, Wilfred “Rosy” Ryan, general manager of the Millers, and Maurice Hessian, Miller treasurer and attorney.

Under present plans the ground breaking and actual construction will start as soon as spring weather permits. Plans are to have the stadium ready for use as early as possible in the 1950 American Association season.

Ryan, who lives in St. Louis Park, announced plans to call for a stadium to seat 17,500 spectators at baseball and around 25,000 for other events.

The stadium will be suitable and available for high school and other football contests, circuses, expositions and other entertainment such as open air concerts.

It is planned to model the plant in general after New York’s Polo Grounds, which, a Giant spokesman points out, is one of the finest football stadiums in the country. And like the Polo Grounds, the Giants intend to keep it busy.

Ryan said there is a bare chance work might progress sufficiently so that the new structure could be used for football next fall.

He said if things went smoothly lights could be in place by August and the gridders could go into action there even though the grandstand probably would still be roofless.

Hessian told The Dispatch Wednesday that the stadium would convert the abandoned gravel pit which is now a collecting place for waste water into a thing of beauty.

“We plan the finest brick structure with beautiful, suburban landscaping,” he said.

At present, the first 135 feet back from the highway is zoned commercial, while the rest of the park tract is open development. All except the first 135 feet fronting Wayzata boulevard is wasteland.

Reports are that the Giants and Millers considered two St. Louis Park sites before making a purchase. The alternate site was reported to be on the Belt Line just north of Lilac Lanes – another gravel pit and eyesore. [Now the site of Byerly’s]

In the same issue of the Dispatch, Halsey Hall chimed in with his support:

Someone said, “I’d have expected a replica of the Taj Mahal before I’d have thought of a baseball park and stadium on Wayzata boulevard in St. Louis Park.”

Maybe that covers the point. But the New York Giants are going for the stadium idea if all goes well and their purpose in selecting a site on Wayzata boulevard and Zarthan Avenue is to give Minneapolis, the Park and all baseball-feeding communities a civic landmark of which they can be proud.

The old days when ball parks and stadia were associated with slum districts are no more…The Giants point out that “a ball game lasts from two hours to two and a half” and a team plays at home only a little over two months a year.”

Miller general manager Rosy Ryan, a St. Louis Parkite himself (3245 Idaho) remarks, “that is true but, when you’re IN a stadium you want to be in a good one. We outgrew Nicollet park long ago, just as any organization or community outgrows the old.” Ryan also recalls that somebody mentioned a circus or two as being an item that could use his stadium but he nixes this.

“There’ll be no circuses,” he says, “anyway there have been times when I’ve seen our ball club give a pretty good imitation of one.”

The availability of parking space is another reason the Giant-Millers like the Wayzata boulevard plot. Residents object to a field near them largely because the streets are cluttered with automobiles, the breaking-up of a game is filled with traffic problems.

Under the present plan there would be none of this for the ball club will have its own huge parking lot, the boulevard would be kept clear and homegoing traffic would fan out via so many arteries that congestion would be virtually unnoticeable.

Just one thing though, folks. Let’s not make that right field fence TOO far away from home plate.

THE MBAA AND THE MINNEAPOLIS MILLERS

The promoters were the Minneapolis Baseball and Athletic Association (MBAA), owned by Giants owner Horace Stoneham. The stadium would initially be built for the Minneapolis Millers. The Millers team dated back to as early as 1884, but joined the American Association as a AAA team in 1902. They played at Nicollet Park until 1955 – it was demolished in 1956 and is now the site of a Wells Fargo Bank branch, built in 1957. In 1956 the Millers played at Met Stadium until the Twins came to town in 1961. The Millers were a local team, but throughout the years they were affiliated with major league teams, such as the Boston Red Sox (1936-38 and 1958-60) and the New York Giants (1946-57). Halsey Hall did the play-by-play from 1933 to 1960 when the club folded.

It was during the time when the Millers were the Giants’ minor league team that a plan was formulated to lure the Giants themselves to the new stadium. Ryan lived in St. Louis Park and was a big booster of the SLP site.

LOCATION AND SIZE

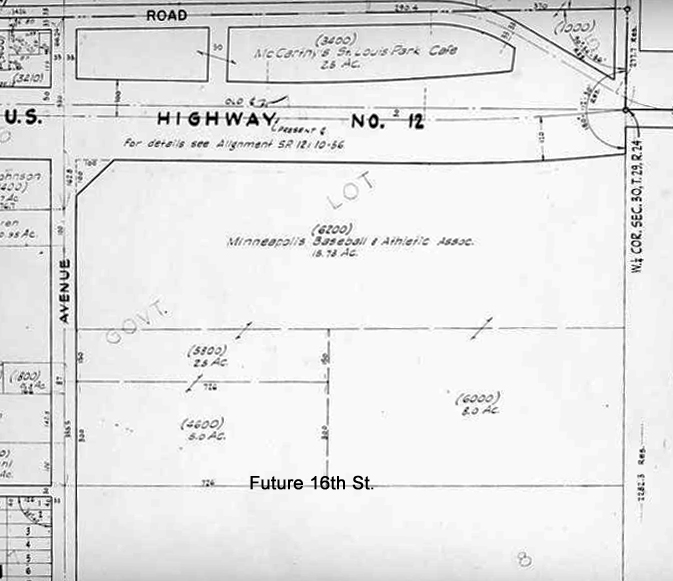

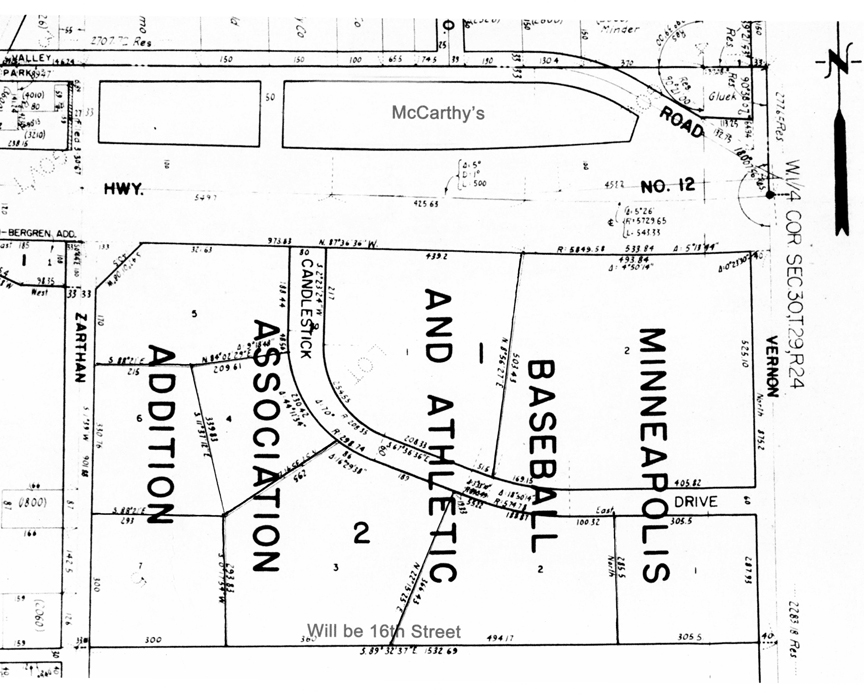

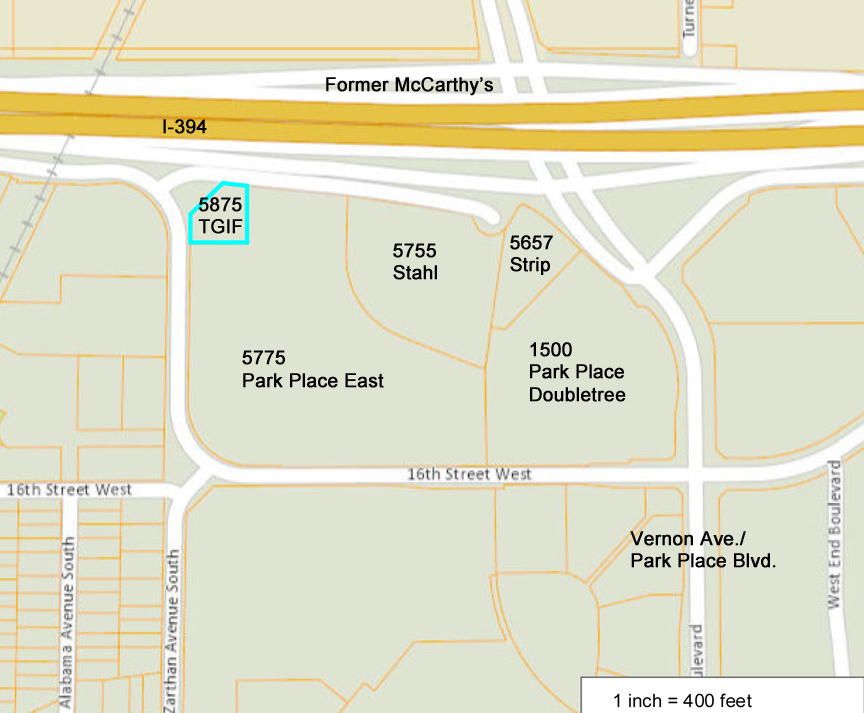

The area of the proposed ball park was in Government Lot 5 of Section 4, Township 117, Range 21. Today this area is bounded by the St. Louis Park/Golden Valley boundary on the north, Zarthan Ave. on the west, what would become 16th Street on the south, and what is now Park Place Blvd. on the east. Lot 5 consisted of 33.8 acres in all.

An odd thing about this parcel is that Highway 12, which generally followed the SLP/GV border, dipped south at this point, stranding 2.57 acres of land north of the highway that was actually in St. Louis Park. McCarthy’s Restaurant was located on this piece of land.

In 1938, a man named Frank Salter owned all but 5 acres of Lot 5. Salter either owned or sold the land to the Minneapolis Sand and Gravel Co., which turned it into a wasteland and an eyesore. In 1942 McCarthy’s was built on its northern outpost, and McCarthy also bought several acres of land in the southern portion of Lot 5.

A 1951 plat map shows that the MBAA site was made up of four parcels. As noted in the 1948 article above, the tract of land for the ball park was initially 20 acres, located at Wayzata Blvd. and Zarthan. By January of 1949, MBAA must have purchased the remainder of Lot 5, bringing the total to 31.23 acres. From then on the tract was described variously as between 31 and 34 acres. One source said that on May 1, 1951, the MBAA purchased 40 acres of land that was all of Lot 5 south of Wayzata Blvd., but that adds up to more acreage than was there, and it’s likely that the sale was made before that – by 1951 the deal was all but over.

Although the property was accessible by Highway 12 and Zarthan Ave., 16th Street did not yet go through on the south, and Vernon Ave. (now renamed Park Place Blvd.) did not exist on the east.

HOMETOWN SUPPORT

From the date of the initial announcement, articles about the proposed stadium appeared frequently in the Dispatch. At the December 20, 1948, Village Council meeting, Recreation Commission Chairman Elmer Dale headed a delegation of people who were for the stadium. Anton Yngve, who owned property in that part of town, brought a petition signed by 60 supporters living on Wayzata Blvd. between Zarthan and Colorado Avenues. “Why, we would be tickled to death to get rid of that eyesore.” Mayor O.B. Erickson declared, “I think it will be a very fine thing for St. Louis Park to have the ball park located here.” The Eliot School PTA had voted in favor of the ball park at a meeting last week, and the American Legion unanimously passed a resolution endorsing the plan.

In the January 7, 1949, issue of the Dispatch it was reported that although the MBAA had not yet applied for a permit to construct the ball park, the Village Attorney is busy drawing up an ordinance for regulation of the park, its construction, concessions, police powers, types of buildings in the area, hours, lights, parking, and Sunday hours.

The next week, January 14, 1949, it was the VFW’s turn to endorse the plan.

At the Village Council meeting of February 14, 1949, the MBAA presented its petition for rezoning the now 31-acre tract. The cost of the “athletic plant” was estimated at $1.5 million. The stadium itself would cover ten acres, and the rest of the property would be used for parking. Another petition signed by 107 property owners in the vicinity was also presented to the Council and referred to the Planning Commission.

After due consideration, the Planning commission recommended the requested rezoning, subject to four conditions:

- That Zarthan Ave. be widened to 80 feet;

- That 16th Street be opened to the width of 66 feet from Zarthan to Highway 100;

- That another street be opened along the east boundary of the ball park property connecting Wayzata and 16th Street [this was Vernon Ave., now called Park Place Blvd., which was built in about 1960]; and

- That the ball park be provided with sufficient parking space so Park streets will be used as little as possible.

Plans called for parking spaces for 4,000 cars. Maurice Hessian, Sr., attorney for the MBAA, assured the council that the park would be available to Legion and high school teams without charge.

On March 28, 1949, the Village approved the requested changes in zoning, providing that the change in zoning was only applicable to the ball park and would be void if the park was not built in five years.

The Dispatch reported, “Although no opposition was presented, H.E. Chard, district engineer of the state highway department, warned of the traffic hazards and problems which the park might create.” Chard made several suggestions:

- The main entrance should be on the east side;

- 16th Street should be cut through to Highway 100 in order to eliminate left turns;

- Exit from the park should be onto the service road of Highway 12, again to eliminate left turns;

- Traffic signals should be placed at 16th and Highway 100, with no left turns permitted on Highway 12 at Zarthan.

Chard also pointed out that the area was not served by any kind of mass transit, and the only access was by way of Highways 12 and 100. “Cedar Lake Road is at present inadequate for heavy traffic.” He pointed out that with the park designed to accommodate 18,000 for baseball games and more for football games, there would be approximately 60 games per season, suggesting that at least 6,000 parking spaces would be needed. “Greatly increased enforcement personnel will have to be provided by the village to control and direct traffic to and from the park,” warned Chard. He warned that the serious increase in traffic would “undoubtedly [result] in a material increase in accidents.” At that time, before underpasses and controlled intersections that we have now, left turns were the source of an alarming number of traffic accidents on our highways.

Regardless of these concerns, hopes were high, and construction was expected to start in the spring of 1949, to be ready for the 1950 season.

But construction did not start in the spring of 1949. In June, Mayor Erickson told the Village Council that he had received a call from Rosy Ryan, assuring him that the Millers are determined to go through with their plans. “They are working carefully,” Erickson explained to the council. “It is a big project and a big ball park. Ryan told me, ‘We’re going to have the ball park, we need it.'”

And then it was 1950. In mid-January, Horace Stoneham came to town and said, “We expect to start work on the new ball park by the middle of the summer. It should be ready no later than the 1952 season. We definitely are going to go ahead and build. We have had architects working on the plans for some time. We plan to get started as soon as all the preliminaries can be straightened out.” Details called for 15,000 seats. Stoneham also said he was “contemplating the idea of building a shopping center fronting the boulevard on the south side.” One obstacle was an old sandpit that had to be filled. Stoneham said, “There is much to be done. I have not made final arrangements regarding land work or building contracts and we still are dickering on that matter. I want to have the finest possible minor league plant when we start.” Temporary bleachers would bring seating capacity to up to 25,000, and the parking was now up to 7,500 cars. The main entrance would be on Zarthan Ave.

The next week, Stoneham was ready to state that construction would start no later than midsummer, 1950, with a possible opening as early as August 1951. The topography of the site may have been causing them problems. The Dispatch reported, “One construction possibility that will be probed is that of sinking the stadium below the present ground level of the site. If this proves feasible, it will reduce construction costs, said Stoneham.”

A hopeful headline appeared on February 8, 1950: “Miller Ball Park Moves Beyond Talking Stage.” Lionel Levy, acclaimed builder of baseball parks, stadiums, and arenas, came to town to inspect the property and gather all the detailed information necessary for architects and contractors. Alas, his report must not have been very good.

BLOOMINGTON

In his book Stadium Games, Jay Weiner writes that at a lunch at the Minneapolis Athletic Club in the summer of 1952, three men actually started the conversation about bringing a major league baseball stadium to the Twin Cities:

- Charles O. “Charlie” Johnson, a sports editor and columnist at the Minneapolis Star and Tribune

- Gerald “Jerry” Moore, sales manager of a storage and moving company, president of the Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce, and eventually the head of the influential Minneapolis Downtown Council

- Norman McGrew, “a tireless behind-the-scenes coordinator of details and a marketer before the term ‘sports marketing’ was part of the industry vocabulary.” In 1945, when McGrew started his 45-year career at the Chamber, one of his responsibilities was to bring major league sports to the Twin Cities.

1953 was significant, Weiner writes. Since 1903, major league baseball enjoyed a Supreme Court-protected monopoly that exempted it from anti-trust laws and kept the same 16 major league baseball teams active in 10 cities. But in 1953, the Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee, making it the first time in nearly 50 years that a franchise had been allowed to relocate. Later that same year, the St. Louis Browns moved to Baltimore to become the Orioles. And by the fall of 1954, the Philadelphia Athletics announced their move to Kansas City.

In each of these cases, the teams had a new or refurbished stadium to move to. Both the Athletics and the Browns had actually approached the Twin Cities as a place to move to, but there was no stadium for them.

Weiner writes that on January 25, 1954, Horace Stoneman of the Giants was in Minneapolis, and spilled his plans to move the Giants to Minneapolis, “probably to the new stadium that would somehow be built on his land on Highway 12. The Giants’ relocation would be part of a move to send the Cincinnati Reds to New York in exchange for the Giants move to the Twin Cities. Cincinnati was then the smallest market in the big leagues.”

But by now many factors were standing in the way of the St. Louis Park site. The most damaging were that the demand for more parking kept growing, and St. Louis Park was deemed too far west to appeal to those in St. Paul.

So despite Stoneman’s persistent dream of building in St. Louis Park, things were not moving in that direction in the hearts and minds of the powers that be back in the Twin Cities. On August 13, 1954, an agency called the Metropolitan Sports Area Commission was formed, backed by Minneapolis, Bloomington, and later Richfield. Bonds were floated to build the Bloomington park at about the same time. This was the beginning of Metropolitan Stadium in Bloomington, and the end of Candlestick Park in St. Louis Park.

The Met opened in 1956 on a 161-acre site.

The sign that proclaimed “Future Home of Candlestick Park,” posted at the southeast corner of Cedar Lake Road and Turner’s Crossroads (where present-day Park Place Blvd., Parkdale Drive, and Cedar Lake Road converge), sadly came down.

AFTERMATH

In 1956 McCarthy’s filed suit to recover 15 of the 30 acres it sold to the MBAA in 1949. These were no doubt the 15 acres that fronted Wayzata Blvd. According to the suit, the Millers paid $35,000 for the 15 acres. In a 1978 article in the St. Louis Park Sun, R.T. Rybak quoted a former employee of the restaurant: “We knew at the time that it was a ridiculously low price but it was sold because we knew a stadium would help business. We wanted to put in the contract that the sale would not be final unless the stadium was built but Stoneham said that wasn’t necessary ‘because we are all men of our word.'” McCarthy’s said it was willing to return the purchase price, pay seven years’ worth of interest and repay all taxes paid in order to get the land back. But the MBAA won the suit and held onto the property for the next 20 years, watching its value skyrocket. It refused offers to sell parts of the property, insisting on selling the entire parcel.

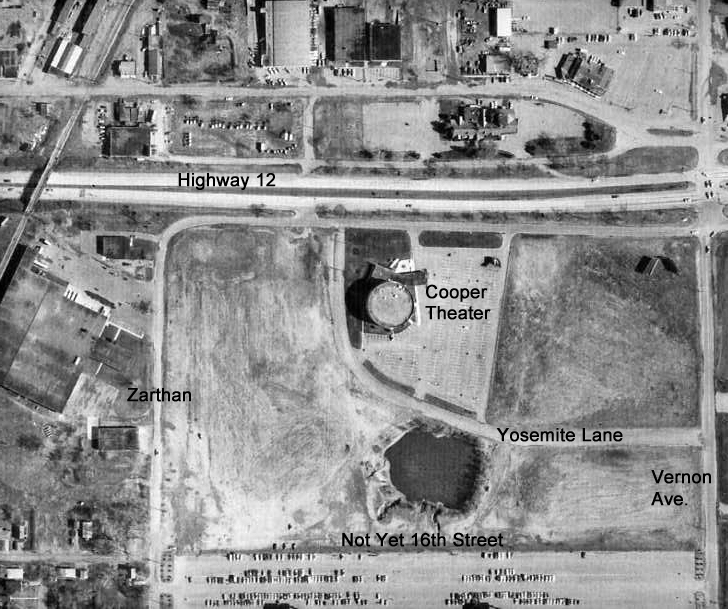

Apparently this stance changed when the property was subdivided into the MBAA Addition on December 29, 1961. Three of the nine lots faced Wayzata Blvd. The plat included a curved street called Yosemite Lane that connected Wayzata Blvd. to Vernon Ave. It was inside this curved street that the Cooper Theater was built in 1962. It was possible that the Cooper only leased the land from the MBAA.

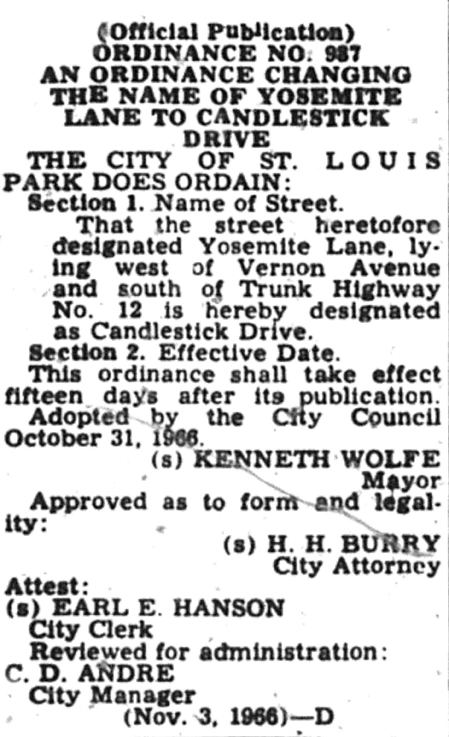

Someone at the MBAA still had a personal interest in the land, it seems: On October 31, 1966, the company was successful in petitioning the St. Louis Park City Council to change Yosemite Lane to Candlestick Drive. The MBAA and Fischer Realty Company had also requested that a portion of Zarthan Avenue be vacated.

In 1974, National Exhibition Co., the Giants’ real estate subsidiary, went bankrupt and was forced to sell the land to a developer. Aerial photographs through 1975 show that only the Cooper and those huge pools of water left by the gravel pit were on the property.

On January 1, 1978, the MBAA Addition was vacated and the Park Plaza Addition was filed for the western portion of Lot 5. On September 26, 1979, the eastern portion of Lot 5 was replatted. Although Candlestick Drive remained for awhile, as buildings went up the curved road with the sentimental name disappeared.

One problem still remained. When McCarthy’s sold the land to the MBAA, a restrictive covenant was placed on it that prohibited the sale of food or liquor on the property except in connection with baseball games or other recreational events. Eventually the then-owner of the land, Turner’s Crossroad Development Corporation, went to court to lift the deed restriction. The court found the restriction no longer operative, since baseball was no longer feasible and such covenants were only valid for 30 years. Indeed, by that time McCarthy’s Restaurant no longer existed. The court deemed the covenant void as of April 23, 1979.

CURRENT OCCUPANTS

Buildings started going up on the former MBAA property in 1980. They are:

5775 Wayzata Blvd.: 1980. Park Place East, a large office building.

5657 Wayzata Blvd.: 1981. This is a strip of shops and restaurants.

5875 Wayzata Blvd.: 1981. TGI Friday’s

1500 Park Place Blvd.: 1981. The Sheraton Park Place Hotel opened on June 6, 1982. Vernon Ave. was renamed Park Place Blvd. in its honor. It has since changed its name to the Doubletree.

5755 Wayzata Blvd.: 1995. This was the site of the Cooper Theater, which was built in 1962 and razed in 1992. After it was torn down, Bradley Chazin took the photo below, “from my old office on the top floor of the Park National Bank Building at Highway 12 and Vernon Ave. ” The original replacement for the Cooper was going to the an Olive Garden Restaurant, but it went elsewhere and the site became the offices of Stahl Construction. The enormous Honeywell building can be seen to the south. It was demolished in 1996 and replaced with Costco.

CODA

Rosy Ryan was the General Manager of the Minneapolis Millers until 1957. He eventually moved from St. Louis Park to Minneapolis to be closer to where the Millers played at Nicollet Ballpark. He stayed with the Giants organization and served as the GM when the team became the Phoenix Giants from 1958 to 1959, the Tacoma Giants from 1960 to 1965, and then back to Phoenix from 1966 to 1973, where he retired.

Despite the change in venue, the Twin Cities remained keen on getting the Giants to move to Minnesota. The New York Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers – fierce rivals – both announced their moves to California in the summer of 1957. The Giants moved to San Francisco and broke ground for their Candlestick Park in 1958. They played two seasons in Seals Stadium before Candlestick Park opened in 1960.

CANDLESTICK PARK

The Giants chose the name Candlestick Park after a name-the-park contest on March 3, 1959. According to Wikipedia, it was named for Candlestick Point, a point of land jutting into San Francisco Bay. Although the hopes to build the stadium in St. Louis Park were gone by 1954, somehow the name Candlestick got attached to the Minnesota property – as we’ve seen, in 1966 the MBAA requested that Yosemite Lane be changed to Candlestick Drive (a street now destined to history). But to this day, Candlestick Pond is located at 16th Street and Park Place.

Star Tribune columnist Patrick Reusse pondered this perplexing question: how did the name Candlestick, so firmly connected to the San Francisco site, get attached to the St. Louis Park site? Here’s his guess:

The San Francisco Seals were a Giants Class AAA farm club in 1946. Stoneham or his nephew, Chub Feeney, was enamored by Candlestick Point Regional Park during visits to San Francisco. They thought it was a cool name and decided to attach it to an area of St. Louis Park that they planned to beautify with a ballpark and surrounding greenery.

We would like to know more about Candlestick Pond (is it really full of VW bugs?) and how it got its name, so please contact us!

SOURCES

St. Louis Park Dispatch: (Many thanks to Stew Thornley)

- Millers Pick Park for Baseball Park, Will Construct All-purpose Stadium: December 17, 1948

- Holy Cow! Whata Deal! Stadium will be Civic Landmark: Halsey Hall, December 17, 1948

- Residents Rally Behind Proposed Miller Ball Park: December 24, 1948

- Legionnaires Back Miller Plans For Sports Park Here: January 7, 1949

- Park VFW Favors Miller Park 100%: January 14, 1949

- First Step Taken Toward Ball Park Project Approval: February 18, 1949

- Lions Officially Endorse Ball Park: February 21, 1949

- Rezoning Hearing Set for Proposed Miller Ball Park: March 11, 1949

- Council Clears Way for Miller Stadium and Ball Park, Approves Site Rezoning: April 1, 1949

- Ball Park Plans “Going Forward”: June 17, 1949

- Work on New Miller Stadium Slated to Start in the Summer: January 18, 1950

- Miller Ball Park Construction Scheduled Midsummer, Latest: January 25, 1950

- Miller Ball Park Moves Beyond Talking Stage: February 8, 1950

- McCarthy’s Cafe Sues to Regain “Ballpark Land”: March 1, 1956

St. Louis Park Sun:

- Bid Farewell to the St. Louis Park Giants: By R.T. Rybak, December 13, 1978

Minneapolis Star Tribune:

- Pondering a stadium history mystery: Patrick Reusse, October 8, 2016

Interview with Bob Ryan, July 2007

Email from Keith Meland, July 2, 2007

Matter of Turners Crossroad Development Co. 277 N.W. 2d 364 (1979)

Stadium Games: Fifty Years of Big League Greed and Bush League Boondoggles, by Jay Weiner. Minneapolis: University Press, Copyright 2000.